'The wards were full of children. Five- and six-year-old children. And children in incubators'

'The city was in complete disarray. The (authorities) didn’t bother much'

'The people didn’t know what happened actually. The government knew about it. (None) of the people knew'

Photojournalist Chandu Mhatre, one of the first to reach Bhopal after India's worst industrial disaster ravaged the city, remembers his worst seven days, in a conversation with Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com.

The strangest commute of Chandu Mhatre’s life was 32 years ago. December 1984. When he travelled daily between Mumbai and Bhopal, and back, for a long and awful week.

The press lensman paid Rs 1,400 for a round-trip ticket (he distinctly remembers the amount) each morning, around 9.30 am, and boarded the 35-seater Indian Airlines Avro that took him, and a motley bunch of fellow passengers – Delhi and Mumbai doctors, American lawyers, international and Indian photographers, television crew and reporters – to a bewildered, wounded city, felled by one of history’s worst lethal chemical gas clouds.

Mhatre would return each evening to Mumbai around 7 pm to file pictures, since communication channels out of Bhopal city were hampered and the images of this crime against humanity needed to go out to the world.

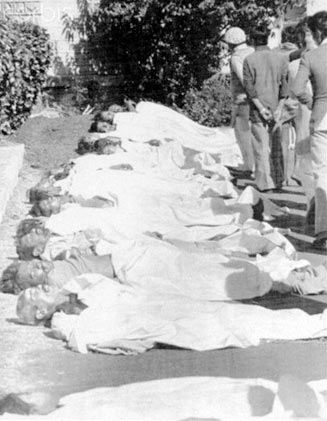

Every day, for seven days, he filed 200-300 photographs. “Black and white pictures. Of bodies. Of children. Of the medical cases. Of the lawyers. Of homes where entire families has died…”

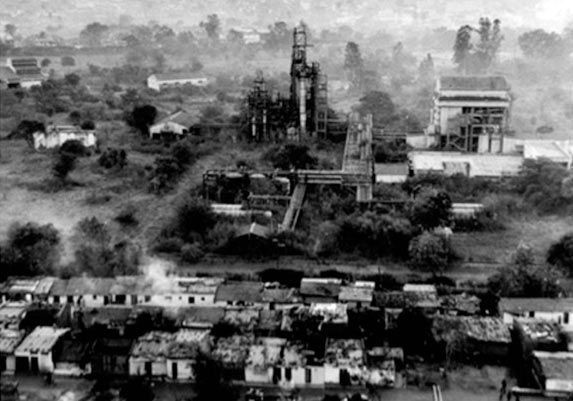

A view into a disaster that killed 3,787 and affected over 500,000, when methyl isocyanate leaked out of the Union Carbide plant on the night of December 2-3.

As soon as the news of that chilling night percolated out of Bhopal by early December 4, remembers Mhatre, the press and lawyers were the only people scrambling to reach Madhya Pradesh’s capital city.

“There were flights to Bhopal. But nobody was going. Contamination was very high. So it was risky to drink the water there. We brought food along with us from the flight. Basically we had a bottle of water with (each of) us.”

He first arrived in Bhopal on the morning of December 4 to cover the calamity for United Press International, the photo agency.

When he reached within a 2.5 mile radius of the Union Carbide factory, near Arif Nagar in north Bhopal, the sight that greeted him was monotonous. Tragically monotonous.

“A series of bodies. Not just humans. Animals also. Lots of children. The cremations had already started happening. Bodies were lying everywhere, on the roads.

“I shot a picture from on top of a hospital -- you could see rows and rows of bodies. Nearly 600 bodies.” That picture, he felt, captured the heartrending reality of the situation.

He remembers the enormous lines of dazed relatives waiting to either bury or cremate their dead. “The authorities were transporting the bodies with their bare hands. They had to be identified to be either buried or burnt. There were mass cremation grounds. Huge queues. They would cremate 10-15 bodies at one time. But a lot of the victims were Muslim. So they were being buried.”

The city laboured under an odd sense of confusion, recalls Mhatre. Anger or deep grief had not really set in. Instead, he says, Bhopal seemed to be reeling from utter disbelief. “They knew there had been a gas leak from the plant. Nothing beyond that. They didn’t know what happened actually. The government knew about it. (None) of the people knew exactly.”

There were about 200 photographers, many of them foreigners, who apparently had got visas on arrival, roaming the city, as well as television cameramen – from BBC, Doordarshan. The factory was sealed off completely while Mhatre was there, but the press could pretty much access every other area. “We were not allowed to go near the plant at all. The city was in complete disarray. The (authorities) didn’t bother much. Photographers could go anywhere. Once you got hold of a local taxi, we could fix for it to take us where we wanted.”

By the third or fourth day, lawyers were crawling all over the impoverished shanty town, once home to approximately 35,000 people, adjoining the Union Carbide plant, with forms filing claims on behalf of the victims against the chemical company. “Every flight you would have 10 or 15, maybe 20, of them, from US legal firms, going in.”

Temporary/mobile hospitals had been set up. “They were treating people for breathing problems. Every hospital was chock-a-block full. They didn’t know what kind of treatment to give. They were giving treatment for burning eyes. Eye drops and things. The wards were full of children. Five- and six-year-old children. And children in incubators.”

When Mhatre was out shooting continuously for those terrible seven days in Bhopal, there was “not much time to think. You had to get your pictures and get out.”

On reaching Mumbai every evening Mhatre would be in the dark room bringing to life his grim frames of death.

The photographer, who has covered many of India’s tragedies – earthquakes in Bihar, floods in Mumbai and Bihar -- says, “It was the worst (disaster) I had ever (covered). A lot of children were affected. India had never seen anything like this. (It was something like) what happened in Vietnam (the dropping of 388,000 tonnes of napalm bombs during the Vietnam war by American military). That was an act. This was not an act. This was an accident. But it was absolutely the worst scene I have seen.”

ALSO READ:

REWIND: Finding Bhopal gas tragedy's Warren Anderson

The Bhopal gas tragedy: 30 years on

How 1984 changed the lives of women in Bhopal

How $ 37.68 a day could have saved Bhopal

© 2025

© 2025