'I can tell you the case that hurts me the most is the one in which the little boy is forced to sign the Kohinoor over.'

'You take a mother away from a child, you surround him with grown ups speaking a different language, you tell him he must sign this over or else...'

The Kohinoor has raised more controversy in history than any other gem.

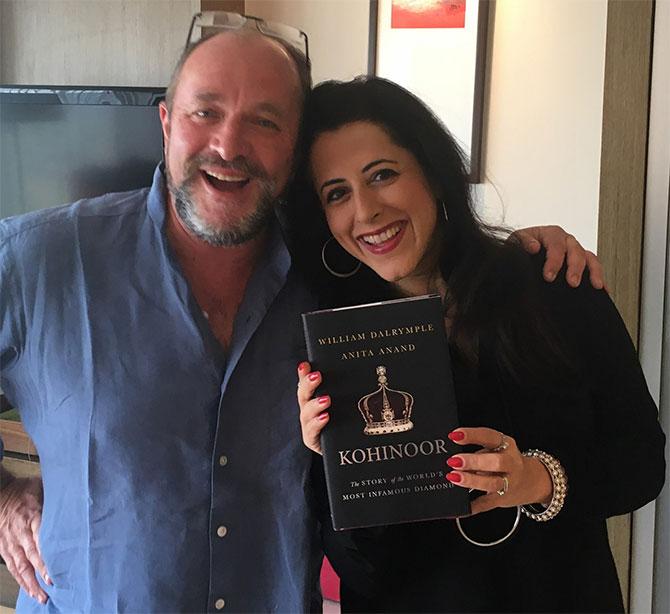

William Dalrymple and Anita Anand, authors of Kohinoor: The Story of the World's Most Infamous Diamond, tell Rediff.com's Vaihayasi Pande Daniel about the diamond's complicated history and what they have learned about the notorious stone while writing the book together.

- There is absolutely no evidence of ownership, till date, of the Kohinoor (now in the Tower of London) before it became a decorative item on Mughal emperor Shah Jehan’s Peacock Throne. There is no documented information on where it came from before that. The first historical references to the diamond, dug out from Persian texts by historian William Dalrymple, date from 1750.

- The Kohinoor is not the biggest or the most beautiful diamond or gem taken from the Indian subcontinent by the Persians or the British. Bigger and better stones, taken from Delhi, sit in the Kremlin, a bank in Tehran and the Tower of London.

- Queen Elizabeth II has never wanted to wear the Kohinoor. Nor has she. It has a reputation of ill luck. Possibly she would not like to be in the eye of a controversy should she appear in public with it on her person.

- The diamond was cut nearly in half by Prince Albert, Queen Victoria's husband, to make it look better! He was advised not to by several scientific experts who feared it would crumble. When the original owner Prince Duleep Singh of Punjab saw the re-cut diamond he could not speak for a few minutes, he was so flabbergasted.

- The British deliberately gave the not-that-large Kohinoor excessive importance as a way of advertising its imperial successes in India. So much so that when it went on display ast the Great Exhibition at Hyde Park, six million Britons queued to see it.

- Most stories you have heard about the origins of the Kohinoor are untrue. But it is true that a man had molten lead poured on his head because of the Kohinoor.

- The Kohinoor changed countries five times! It has travelled to Iran, Afghanistan, Kashmir, Punjab, Bombay, around the coast of Africa, Plymouth, Portsmouth and Buckingham Palace. It also survived a sea journey that almost saw it reach the bottom of the Indian Ocean.

- The British will probably never give the Kohinoor back to India. If they considered returning it to the country of its earlier ownership, they would have to decide whether to give it to Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan or India!

- Go to the long read to learn much more about this haunted, bloodthirsty diamond.

When television and radio journalist Anita Anand was a pigtailed girl of five, she and her family would often visit the forbidding Tower of London.

Like all well-knit Indian immigrant families settled in Britain -- her parents arrived from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa after Partition -- relatives and family friends were always popping in from India to see them.

They, of course, had to be shown around London's Patel Points. The tour was almost always exactly the same. To Madame Tussaud's to say cheese with Mahatma Gandhi. Off to the Marylebone road London Planetarium (that no longer exists) to gaze curiously at the ceiling. And then to the Tower of London on the Thames "where everyone wanted to make rude comments in front of the Kohinoor diamond!" she recalls.

That diamond was usually impossible for the wee Anita to spot. Firstly, it wasn't all that large. Inversely, the excited crowd gathered to see it was huge.

When she finally got a chance to peek at it, invariably from an adult's shoulders, with her father giving the necessary instructions -- "Not that one. Down a bit. Not that one. Left a bit" -- she could never understand what the fuss was about, given in the same jewel case there was the tennis ball-sized Cullinan diamond.

What a rumpus over nothing! What a tempest in a tea pot!

But unlike the real heavyweights in the world's gallery of grand ol' stones, many from India -- like the enormous Cullinan diamond (530 carats), the stunning Timur ruby (361 carats), the elegant Orlov (190 carats), the unusual Samarian spinel (270 carats), the right royal Daria-i-Noor (182 carats), the pretty Jacob (184 carats) -- the Kohinoor owns a reputation and commands attention far, far beyond its comparatively paltry 105 carats.

Why?

The Kohinoor is a wonderful illustration of how history is often written to misleadingly trumpet the deeds of the conquerors. It is never a tale of the vanquished.

Back in 1848 the British were inordinately pleased with themselves for having been able to, oh-so bravely, using the might of their army and the smarts of a scheming governor general, swipe the then un-cut, 186-carat diamond from a frail, family-less Sikh boy and rush it to England for Queen Victoria to wear proudly as a badge of the Empire's successes.

But they overdid the tom-toming of its importance. Overdid the history.

It came back to bite them.

When the empire crumbled, and history began to correct itself, the Kohinoor, not ever the flashiest stone in the world, in spite of its name which means Mountain of Light, instead mirrored the empire's ugly excesses and its guilt.

Regardless of its less impressive size, the interesting winds of history that have carried the mysterious Kohinoor, through multiple historical hands, across three continents, have made it an object of limitless fascination and controversy.

Look into its dazzling face and the stone raises hundreds of questions.

Like: How did the diamond travel from Delhi to Persia and then to Afghanistan, Lahore, Kashmir and Mumbai?

Where was it mined?

Why was it considered unlucky and is no longer worn?

How did it almost sink to the bottom of the Indian Ocean?

Why did six million people queue to see such a small diamond at London's Great Exhibition? Why did they leave unimpressed?

Why did Queen Victoria's husband Prince Albert have it cut in half?!

Why did Victoria ask Prince Duleep Singh's permission to wear it?

Why do the pandits of the Jagganath Temple, Puri, seek the diamond?

Did the diamond ever have a country?

Anita Anand and William Dalrymple got a sharp sense of its continuing enticement the day Dalrymple decided to organise a one-hour talk on the Kohinoor at the London Southbank JLF between him, Anand and then Indian high commissioner to the United Kingdom, Navtej Sarna, who has written The Exile, a well received book on Duleep Singh.

Anand was fairly sceptical about what they would talk about for one hour that evening, being no specialist on the diamond although she had written Sophia Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary, a book on Duleep Singh's daughter.

She thought the discussion might be a "fantastically public car crash," but instead discovered that each of them in turn had so many interesting historical anecdotes to relate about the stone. "And you could hear a pin drop in the room."

Their discussion continued to the green room, over wine, and they decided that a more accurate account of the history of this "Rock Star," as Dalrymple calls it, had to be jointly written.

Anand and Dalrymple buckled down to do that -- Sarna had to bow out due to his official duties -- and what a journey it has been. Coordinating the research and writing across 8,000 miles had its exciting moments.

Dalrymple and Anand spoke to Rediff.com's over the telephone about their book Kohinoor: The Story of the World's Most Infamous Diamond and what they have learnt about the world's most famous diamond.

You have written extensively on the Mughal dynasty. What kind of different experience did writing about the Kohinoor afford? What did you learn about those times or about the Mughals, writing this book?

William Dalrymple: The whole point about the Kohinoor book is that almost everything that has said about its history is untrue.

There is a huge biography of the Kohinoor, available in any of the previous books on the subject. Or even the Wikipedia page, or anything, which gives this long history: Housed since antiquity in the temples of the South Indian Kakatiya Dynasty... Said to be one of the eyes of an idol... Alauddin Khilji gouged out the eyes of those idols... It came to the Mughals. (Mughal king) Muhammad Shah Rangila hid it in his turban... Rangila and Nader Shah swapped turbans...

All of this stuff is total nonsense. Not a single bit of evidence for any of it.

Matter of fact, there is not a single reference to the Kohinoor at any point before 1750. This is something local specialists have been aware of for a time and been quietly irritated by way this mythical history is doing the rounds out there.

There is a huge disparity between the actual factual historical reality of the stone and the legend which surrounds it, which is full of completely unverifiable facts.

For a historian it is exactly what you are looking for.

It is a very exciting for a historian when you find that, find an iconic object, which everyone has heard of -- the Kohinoor is famous (across the globe) -- but its history in completely at odds with that widely-perceived, popular perception of it.

What did it teach you about the Mughals?

Dalrymple: It is a book about the diamond. Not about the Mughals.

One thing I learned was that the Mughals didn't particularly like diamonds. For them the greatest stones were rubies or spinels (black gems).

What seems to have happened was that the British created the myth of the diamond, by bringing it to London, bringing it to the (1851) Great Exhibition and turning it into a symbol of imperial conquest, making it an exotic object of India, which six million people queued to see in the Great Exhibition...

Up to then it is completely invisible, in sultanate and Mughal sources. There isn't a single solid reference to the Kohinoor. It is only when it is taken by (Persian conqueror) Nader Shah that we get the first historical reference in 1750 by Muhammad Kazim Marvi (who chronicled the history of Nader Shah's reign).

It is almost exasperating to see how this mythology grew up and how far it is from the reality. Fascinating stuff for a historian.

The crucial first reference to the stone -- is in Muhammad Marvi's work, which is our big find -- says specifically that it was part of (Emperor Shah Jahan's) Peacock Throne.

But it is fascinating that the Mughals never actually (referred to it)... they single out the Timur ruby, which is also on the throne, saying that was the highlight of the throne.

There is no mention of the Kohinoor at all in Mughal sources. Totally absent. Suspiciously and mythically absent.

It is only really with (Maharaja) Ranjit Singh (who founded the Sikh empire in the 19th century) that it becomes the supreme gem.

He also builds value into the stone?

Dalrymple: He is the first person to really give it importance... The stone becomes famous only when Ranjit Singh begins to wear it.

It becomes world famous and a total rock star only after the Great Exhibition,

What is your position of what the British did for India? Were they conquerors, but not all that bad rulers?

Do you agree with what Shashi Tharoor wrote in Area of Darkness that Raj rule ruined India?

Dalrymple: This is something I have been writing about for 20 years. Yes, I am broadly in agreement with Shashi.

British rule had many negative effects. I also agree with him that like the Germans have come to terms with what they did during the Holocaust, I think the British have yet to come to terms with what they did.

There were many atrocities... It is not taught. It is not in the school curriculum. They (the British public) are ignorant about it. I think a great deal of education needs to take place.

I can't see any reason why we can't have an apology.

For Jallianwala Bagh when the queen or (former prime minister David) Cameron went there. Of course, an apology is absolutely essential. I don't understand why there is any hesitation at all in that.

Where do you disagree?

Dalrymple: Where I differ with Shashi is that he creates a slightly angelic and Eden-like picture of pre-colonial times.

He states in his book that the British had punitive levels of taxation. I certainly agree there was very harsh British tax.

I would argue that it wasn't radically different, in that sense, from previous rulers. All rulers exploited.

That was the nature of imperial government in the pre-modern period. And the same was true for most places on the globe.

Governments were there to extract a fortune. They didn't see their job as there to provide infrastructure or education or all the things we feel a modern governments feel responsible for.

In matters of taxation the British weren't harsher than the Mughals and the Marathas, who for instance (taxed its people) 45 per cent in many places and provided no services in return; basically predatory outside their own heartlands.

I wouldn't disagree over how exploitative the British were, but there was a continuity with (earlier) regimes, rather than a striking contrast.

History is full of brutal rulers and atrocities... I think, almost all history, before the modern era, is full of massive human rights violations, appropriations and conquests.

And the history of the Kohinoor says that very neatly: History is full of violence and greed and, in general, the strong taking out the weak.

Do you think the Kohinoor should be given back?

Isn't part of the spoils of wars?

Dalrymple: In this book our job is to distinguish facts from fiction.

As historians we have to go in there objectively, analyse the evidence, uncover new sources, try and work out its history, not geography or take political decisions to try and dictate (its future).

Shashi can do that! He is a politician.

We are providing the (paper) work for any future extradition cases, but we are not taking positions.

So much that has written about the diamond is, in a sense, political posturing.

I think it is very important in a sense if we don't take a position. This is an attempt by an Indophile Brit, living in India, and an Indian, living in Britain, to try and establish the solid facts.

The problem with the Kohinoor is that it has got this fog of mythology around it.

Even the Indian solicitor general (Ranjit Kumar) in April made this bizarre statement that the Kohinoor had been given by Ranjit Singh, when it was neither given and Ranjit Singh was ten years dead.

So it seems the most important thing of the moment is to establish its history.

We provide the evidence and other people can make up their mind.

Anita Anand: There have been so many political polemics on the Kohinoor.

What we were very keen to do was to blow away the mythology around the gem.

Politicians, from many different countries, often get the facts completely and sometimes catastrophically wrong -- a case in point being your solicitor general (Ranjit Kumar), who came out and made some very weird statement about Ranjit Singh making a gift of this diamond to the British.

Well a. It wasn't a gift. And b. There was no way he could make it since he was long dead when the British took the jewel from Lahore.

So we wanted to show the multi-faceted and very complicated history of this diamond.

It is for the lawyers and the politicians to thrash this out now.

If you like, we have done the casework for them.

The Kohinoor tells the story of nations and empires. And you can pitch for it depending on which side of the argument you happen to be.

If you were British it represents power and dominion of the Raj and the British empire. And the just spoils of war after the defeat of an enemy.

For Indians and Pakistanis it represents colonialism and trhe leeching of treasure and trust.

For Afghanistan it means something completely different.

For Iran it means something different still.

If you look at who had the Kohinoor and who got it historically, who do you think really owned it?

Anand: I can tell you the one who wrenches at me the most.

Again, we don't take a position deliberately because this matter is so complicated.

I am not trying to evade your question -- honestly I'm not! But this stuff really is complicated.

I can tell you the case that hurts and nags at me the most is the one in which the little boy is forced to sign the Kohinoor over. There is just no arguing with that.

It happened. You take a mother away from a child, you surround him with grown ups speaking a different language, who are in military or State regalia, you tell him he must sign this over or else...

What else is he meant to do? How can anyone call that a 'gift'? It beggars belief!

There is a whole line of documented evidence to say what went on there.

It doesn't feel right or feel good.

The seizure of the diamond from Duleep Singh was not a straightforward case where someone came in and fought a battle and seized it from a grown up.

There was something so brutal and underhand in the way in which it was done.

Even Queen Victoria was uncomfortable. She wouldn't wear it until she had permission from Duleep. It was problematic, fraught even then...

And your view?

Dalrymple: My personal feeling is that I would certainly support apologies for atrocities and education made (available) about the Empire and all its enormous, varied brutalities into curriculums, but I am actually against in principle the idea of emptying of museums across the world and sending everything back home to where they came from.

In the 12th century, famously, the (South Indian dynasty of kings) Cholas, an army from India, destroyed Anuradhapura and Poḷonnaruwa in Sri Lanka. They burnt the temples and the city to the ground.

The Anuradhapura Chronicles says very clearly that the Cholas broke the idols and took all the jewels back to India.

Should Sri Lanka start suing India for the return of the jewels?

It happened throughout history and not just during colonial times.

Should we start suing the Italian government for what the Romans did in the first century?

It is never ending. History is full of violence. Where in the world hasn't there been violence or a conquest at some point?

And the Kohinoor specifically is a bad example because it has been all over the place. It is very hard to know where it came from.

Dalrymple: Exactly. Completely true.

But what do you think about giving back?

Anand: I think it is unlikely to happen.

The British said there is no way they will give it back.

Let's see, but I would be surprised if they budged on this.

They said it very categorically. David Cameron said it.

Anand: Yes!... Privately if you talk to people high up in government they say: 'Where would it stop? There are so many people who want so much stuff back. We will have nothing left in our museums and galleries.'

When we did We The People (Barkha Dutt's show on NDTV where Dalrymple and Anand discussed their book) the audience was filled with young people who are very passionate about this subject.

Even those people who didn't want the diamond back, per se, wanted some acknowledgment of what had been done to their country and their people during colonial times.

What they are saying: 'Tell our story. Tell the proper story.'

I was born and brought up in the UK. I studied history at school in the UK. And none of what I learned in my researching of the Kohinoor was ever taught to me.

Our mass media always presents the Raj so beautifully.

Benign maharajas playing polo after tiger shoots with men in jodhpurs. I think we should acknowledge the truth.

That is even more valuable than the diamond.

Before you knew exactly what the historical implications of the Kohinoor were, when you first saw it, what did you think?

Anand: It is not the biggest diamond in the world. It isn't even the biggest diamond in that particular display case in the Tower of London.

When I first saw it, it took my eyes ages to locate the Kohinoor.

My dad would say: 'Not that one. Down a bit. Not that one. Left a bit.'

When I finally saw it, I was expecting something out of a fairy tale or something. The diamond was not as vast as my imagination had made it.

The history and the passions surrounding that diamond are planetary in size! The diamond looks small in comparison to expectation.

You were as disappointed as the British public who came to see it during the Great Exhibition?!

Anand: Not as disappointed as they were.

It is a very beautiful stone to me. But it wasn't as big as my imagination had made it, that's all.

It wasn't so large that I understood, at first, why all these people were coming over from far away to see it. And why they would stop (to see it) and get so excited.

When the British saw it in the Great Exhibition it was cut in the Mughal style. Twice as big as it is now, but it shone less than half as much.

They hated its lack of sparkle. They were downright rude about it!

Do you think it was much, much, more beautiful originally? Or have we gotten used to looking at diamonds that are cut in that particular way and we wouldn't like a pebble?

Anand: We know exactly what it looked like before. There are details. Pictures from the time it was in Ranjit Singh's court...

For a start it was twice as big as what you see in the case now. That cutting halved it in size.

But it didn't sparkle like the diamonds we are used to these days, diamonds you get in an engagement ring.

It was cut in a local style... it had a great flat plane on the top... It would have been (impressive) for its time. It would have been awe-inspiring actually.

But it wouldn't have been the kind of diamond a Western palate appreciates. Or indeed a modern palate.

We are used to seeing diamonds sparkle. In the weak British sunshine it needed to sparkle more than ever!

Willy (Dalyrymple) writes in his half of the book that one man had no idea what it was and used it as a paperweight.

And apparently (John) Lawrence (commissioner of Jalandhar district, Punjab and later viceroy) lost it in his waistcoat and the (valet dealing with) his laundry thought it was a chunk of glass.

It is fair to say -- this diamond has had mixed reviews.

Why do you think Queen Elizabeth II doesn't wear it?

Anand: It would really have pissed Dalhousie off (James Ramsay, the earl of Dalhousie, governor general of India, who took the Kohinoor from Prince Duleep Singh) if he were still alive, that the idea of a curse had taken hold in his country.

Even in his lifetime, when Queen Victoria expressed concern about the diamond's bad luck, he said, 'Let her bloody give it to me if she is that worried. I will wear it.'

Also, there is a sensitivity.

I am absolutely sure Queen Elizabeth II has it in her mind that if she were to go to very high-profile public events, with it in her crown, it might ignite an almighty diplomatic row.

So it is a bit of both? She is careful enough not to want to hurt sentiments?

Anand: Very much, a mixture of both.

Not so much as hurt sentiments, but cause a spectacle.

It makes the curse come to life if you have a diplomatic incident. That's the very definition of a modern political curse -- having two countries going hammer and tongs over a rare piece of jewellery.

So that's why again she doesn't wear it...

What did writing this book teach you?

Anand: It taught me, first of all, that stories you think you might know like your own family history are more complicated than you think.

Every Indian is brought up on the idea that the Kohinoor is Indian, has always been Indian and has to go back to India.

And you go to Lahore and you will hear the same thing coming from (there)!

I had spoken to sardars here in the UK, and in India, who say it is a Sikh jewel and has to go back to the Golden Temple and 'I don't even know why you are arguing about it.'

Every side is incredulous that there can be any other eventuality. That was an eye opener.

Also, how this very cold piece of stone still ignites such heated passion. That still surprises me.

The other thing it taught me really was how very, very, bad we are at writing women's history.

Some of the most difficult (passages) I had to write (and will ever have to write) are the scenes of sati that took place -- this enormous (amount) of royal bloodshed after the death of Ranjit Singh.

There comes a time when the guy, whose diary I was looking at (Austro-Hungarian doctor John Martin Honigberger), talks at length of how disgusted he was by the whole thing.

He talks of the slave girls of the queens who went to their death too and how horrific it was. He doesn't name them.

I tried, for a very long time, to find the names of these girls. They had to be named. They had to have names. I couldn't find them!

I believe that to be a great failing on my part.

As you went on through the history of the time and through Honigberger's account of it, there were more and more of these satis and cremations.

The descriptions got scantier and scantier and scantier. It was like these women had dissipated like ash.

They were individuals once. They were interesting and they were almost certainly loved by someone.

When history erases you -- it is a fate worse than death.

And even those who did not burn -- Maharani Jindan, (for instance), she was one of the most extraordinary characters I have come across in history.

She is amazing. But so few people know her story. It's wrong.

What is the historical symbolism of the Kohinoor? Also what is the Kohinoor a symbol of in history?

Dalrymple: The (myth) that the Kohinoor is the greatest diamond in the world, and a symbol of colonial conquest, was something that the British created.

Now, in a sense, it has come back to haunt them.

The British took this diamond -- that really wasn't very well known outside of the Punjab -- and isn't referred to in any Indian sources, that we can find -- and turned it into a symbol of colonial loot which is why it is a live issue.

No one is asking for the Daria-i-Noor (also stolen by Nader Shah and now located in jewel collection at the Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Tehran) back.

No one is asking for the Orlov (in the Kremlin, Moscow) back. They are larger diamonds.

The reason they are asking for the Kohinoor back is because it is a small symbol of colonial loot and that whole baggage.

The Great Exhibition created the myth, where it was put on display as a symbol of colonialism.

Anand: You are absolutely right. Nobody asks about the Timur ruby or the Orlov. Why?

Well, it's the relationship between Britain and India that makes the Kohinoor so vivid and alive.

The Kohinoor has always been much more than itself. The ultimate show of power and dominion.

When Ranjit Singh took it from Shah Shuja, he was jubilant because it was a very visual sign that he had in the north of India in his thrall.

Until he had united all these diseparate misls in the north, Afghanistan had regularly raided villages and settlements.

It was Ranjit Singh who said, 'We unite and fight. We make this our empire.' And it was unprecedented time of unity in the north.

Punjab was strong and wealthy. And Ranjit Singh wore the Kohinoor, on his arm, almost like a shorthand for: 'Don't come here anymore, mein hoo yahan (I am here).'

I would suggest that there were others who also aspired to wear it because it would have shown them to be all-powerful too.

The British definitely had their eyes on it for that very reason. It represented not just the conquest of the north, but crushing of resistance in India.

The north was one of the last bastions to hold out.

India was a place that most British people would never visit. The queen of England would never see it with her own eyes.

The Kohinoor acted like an Alice in Wonderland mirror. She and they could tumble through it and get a sense of their own power in the world.

Do you think it was criminal that it was cut?

Anand: I think it was stupid. He (Prince Albert, Queen Victoria's husband, who organised the cutting of the diamond) had experts telling him not to cut it.

The thing about the Kohinoor, which was why it was so magnificent, was that it was a whopping great diamond of its day -- the biggest.

Albert's efforts halved its size. It is now only 105 carats.

If people are telling you, as they told Albert, from the scientific point of view, 'don't do this... -- and I am married to a scientist by the way -- I tend to listen.

He should have listened to them -- waited for better technology maybe before attempting to give that poor stone a facelift.

The Mughal fascination for gems and their limitless materialism strikes one as disgusting.

At the same time one realises their appreciation for beautiful objects led to their art, wonderful architecture.

It gave us the Taj. What kind of judgment do you make on that?

Dalrymple: They were great aesthetes. They were very visually minded.

They seemed greedy to pursue and want to own so many fine things. On the other hand they gave the world some of the most precious things to look at...

Dalrymple: I don't think greedy comes into it.

They were the richest monarchs in the world. And they were very visually engaged.

They loved beauty. For them gems, particularly red gems, rubies and spinels. They had genuine interest in those. They were experts on this.

No one can claim that the Mughals were ascetics. Or monks.

They revelled, of course, in their power of wealth, so much so that the name of the dynasty is a synonym for power and wealth.

Which is why people today describe Donald Trump as a property mogul!

The word came to be synonymous with this period, due to people like Sir Thomas Roe (the English diplomat of the Elizabethan era) seeing (Mughal emperor) Jahangir hung with jewels. The Mughal dynasty came to be associated with this.

I wouldn't say it is disgusting. It is par for the course in courtly life.

There is no question that the Mughals took more interest in jewels than many rulers. It was something that Indian rulers, as a whole, tended to hoard and value.

There are many references to the rajas of Vijaynagar taking great pride in their jewel collection.

The Mughals took it to an incredible extreme. All part of life's rich tapestry.

I wouldn't want to lead the life. But I don't think we should make value judgments on them.

In the same part of your book where you mention Roe's visit to Jahangir's court you make a reference to the English courts and their dull codpieces...

How much more grand were the Mughal courts?

Was there much more to admire in the Mughal courts of India than the European courts or specifically the English courts?

Dalrymple: The Mughals were the most magnificent rulers of their day.

There is no comparison. The courts of Elizabeth the First would have been nothing compared to this. Completely different order of magnificence. Brilliance.

Because they were just so wealthy?

Dalrymple: They were wealthy. They were stylish. They were sophisticated. Baburnama was one of the greatest diaries ever written.

Jahangir was like an enlightenment ruler. He was fascinated by science, always trying to dissect things. And a great admirer of reason.

They were extraordinary rulers/people. Jahangir was one of the most fascinating. We prided ourselves in Europe on enlightenment. Unwillingness to take anything without suspicion, without checking it out.

Jahangir was all that in the 17th century. Extraordinary.

What part of Anita Anand's work did you wish you had a stab at? And missed doing? Because you were doing the former part.

Dalrymple: I loved working with Anita.

But I got extremely jealous over how good her end of the story was.

My favourite piece is the ship, when the (HMS) Medea takes the diamond (to England).

First, cholera breaks out killing all the sailors. And then it sails into a typhoon.

Straight out of a movie. Like a horror film.

Also, that extraordinary succession of five Sikh murders.

It was huge buzz working with Anita.. It was a lovely experiment in collaborating with someone. She was terrific, Anita.

She is very funny. Wonderfully witty. Terrific company.

We would ring each other up breathlessly. She was in London I was in Delhi (without much regard for) time zones.

'You have no idea what I just found!' 'Oh my god one of my guys has just been covered in molten lead.' 'Mine is just being beaten to death'... (Laughs uproariously).

We had great fun. We are having fun touring together. She is a wonderful speaker.

There is definitely an element of competition in that. Particularly, how we fancy ourselves on stage.

It is rather intimidating to have someone on stage who is a significantly better speaker, never speaks from notes. Wonderfully eloquent. I had to raise my game.

Which part of the story that Mr Dalrymple told you would have like to have told?

Anand: I absolutely loved the stuff about finding the diamond hidden in strange places. Cracks in the ground. On the banks of a river!

What he did was an amazing spell of detective work to find this diamond in the pages of Persian texts, which have never been examined before.

It is just so extraordinary -- that experience of finding something new -- which flies in the face of what the world thought before. Would have been thrilling.

I do envy him hugely, for finding, for the very first time, textual context which says the diamond was in the Peacock throne of the Persians... I loved that.

Being the first person to say: 'It's here!' That's a lovely eureka moment.

How was it to work with Mr Dalrymple him on this project?

Anand: He's delightful. He's such a big kid. Full of enthusiasm and wonder and fun. Just lovely.

Any parallels between the way history was unfolding around the Kohinoor diamond in Iran and what is happening with ISIS today?

Dalrymple: ISIS is not capturing, but destroying (treasures).

Nader Shah took local treasures and treasured them. ISIS is taking and destroying them.

I was in Iran last year (2015). Iran is a very modern and peaceful place. No comparison between the violence of the Persia of Nader Shah and contemporary Iran.

People have some crazy idea about Iran. Iran is an amazing country. And the safest place in the Middle East.

Are there any modern day parallels to the history surrounding the acquisition and passage of the Kohinoor?

Any other object anywhere in the world that had this kind of impact or checkered history?

Anand: I can honestly say that I haven't. This Kohinoor diamond has a talismanic power that I have not seen in relation to anything else...

Dalrymple: I don't think there is any other object. Which is why it was worth writing about.

It has a most extraordinary history. Wherever it goes, it creates bloodshed, division and huge controversy...

You have managed to construct a very linear account of its history.

I can bet while you were researching it, the history must have gone all over the place.

How did you go about putting this story together?

There must have been hundreds of leads you chose not to follow?

Dalrymple: As a historian your job is to troll through quite massive material -- just like sieving for diamonds in the bed of a great river -- as a historian you wade through great massive materials and then you find a diamond anecdote, a glittering little fragment there.

It is rather like sieving for diamonds, frankly. You have these moments when you come across these sparkling gems...

The biggest one I experienced was finding how the gem had come off the Peacock Throne (in) Muhammad Kazim Marvi's chronicles (of Nader Shah's reign) and the very first reference to the Kohinoor.

That was like a diamond to me.

Video and slide show created by rediff.com's Rajesh Karkera and Ashish Narsale.