'It was the first document he had seen that asked him about his past in such detail; it was the only interest this country (America) had shown in his origins, and it was most inconvenient. To get ahead, he had to find out where he had come from.'

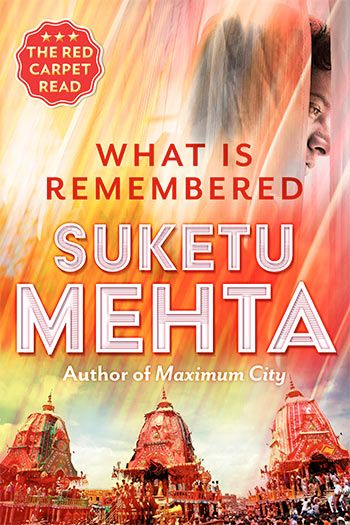

Award-winning New York-based author of Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found, Suketu Mehta's latest short story is about Mahesh, who has a perfect NRI life in the USA -- so perfect that he can't remember a thing about his past in India, not even his mother's name.

An accidental trip to New York's Indian neighbourhood, Jackson Heights, brings back old memories.

Read on for a delightful, exclusive excerpt.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

When Mahesh stepped off the plane from India at JFK, his first experience of the new world was a powerful static shock from the carpeting. It was so powerful that he vibrated in place for a moment, and then sailed forth into New York, humming with energy. Goddamn New York! Fast cars! Zoom!

He ran past immigration, past baggage claim, past customs, and leapt into a taxi, which carried him at great speed to his university. Mahesh's subsequent career, at the university, in the business world, was marked most of all by this energy: He did everything slightly faster than others. Unfortunately, the static charge had also wiped out a small but vital part of his memory: His mother's name.

This in itself would not be such a disaster; he always referred to his mother and thought of her as 'Mummy,' but what was distressing was that, since forgetting his mother's name, he was gradually forgetting other things about his family too -- such as his father's occupation, where his grandparents lived, the correct term for his maternal uncle, his caste.

But as the years went by and Mahesh forgot more and more, he worried less and less about it -- after all, he was well settled in American society; he was in a part of the country where there were few Indians and nobody asked him more than a few cursory questions about his origins such as 'Where's your family?' 'In India.' 'Are you Hindu or Muslim?' 'Hindu.'

Gradually, this was all that was left in Mahesh's memory, that his family was in India, and that he was Hindu.

What was his family doing? Were they dead? Did they come to America and try to contact him? Did they write letters to his previous addresses, which were sent back? Were they angry with him, had they given him up for dead, had they also forgotten his name?

Mahesh did not know the answers because he had not even asked the questions.

And all that remained with Mahesh of the things he had brought over when he came was something he had found in his pocket, whose purpose or significance he could not explain: A hairpin, an ordinary, black, woman's hairpin.

* * *

Just after he turned 30, Mahesh found that he had to become a citizen of the United States of America. He had to do this because he had been given a promotion, a very big promotion, in his company. But to get this position, which involved matters of national security, he had to be a citizen.

Just after he turned 30, Mahesh found that he had to become a citizen of the United States of America. He had to do this because he had been given a promotion, a very big promotion, in his company. But to get this position, which involved matters of national security, he had to be a citizen.

On the application, he was asked, very clearly, to write his mother's name. He put down his father's name (because it was his middle name, written on his Green Card) but try as he might he could not remember his mother's name. And so many other things depended on his remembering his mother's name -- he guessed that if he knew it, he would also be able to fill in a lot of other details in the application, such as his place of birth and his past addresses.

It was the first document he had seen that asked him about his past in such detail; it was the only interest this country had shown in his origins, and it was most inconvenient. To get ahead, he had to find out where he had come from.

* * *

What Mahesh did remember was where exctly he had forgotten his mother's name -- at the JFK airport. He thought he would go back to JFK and walk around the place where he had lost his mother's name -- maybe he could find it again.

One day, Mahesh got up very early and drove to JFK. The International Arrivals Building. The morning Air India flight, during the holiday season known as 'the dada-dadi bus.' Bringing a vast army of grandparents come to remind their offspring about the values they had left behind: 'It is not this, it is not that.'

Mahesh could see from the glass window above the customs hall the old people explaining the strange contents of their luggage to the American customs officials. They pulled out sarees and kurtas, thick winter clothes made in Kashmir and bottles of perfumed hair oil.

But mostly -- for what else can a poor country offer the West? -- their luggage was a larder, a storehouse of strong-smelling food.

Spices: Asafoetida, turmeric, mustard seeds, wrinkled black pods with no name in any European language. Lentil wafers, sago cakes. Homemade brinjal pickles. Chachi's tea masala. Betel nut and rose water. And always, in the hot season, mangoes.

Mahesh could see the customs officers, sometimes with the help of dogs, anticipate the hoard of mangoes. "Sorry, ma'am, you can't bring this in."

"But it is for my grandchildren!" Such astonishment, such pain, on the faces of the old people! These were the best Alphonso mangoes they could find, two thousand rupees a kilo, never before in their lives had they bought mangoes at two thousand rupees a kilo!

Some would try the time-honoured ways. "Sir, you can take half. For your children," they would offer the customs officer. No, Mahesh shook his head, didn't they realise, they were in America now.

Excerpted from What Is Remembered by Suketu Mehta, with the permission of the publishers, Juggernaut. This book is exclusively available on the Juggernaut app.

© 2025

© 2025