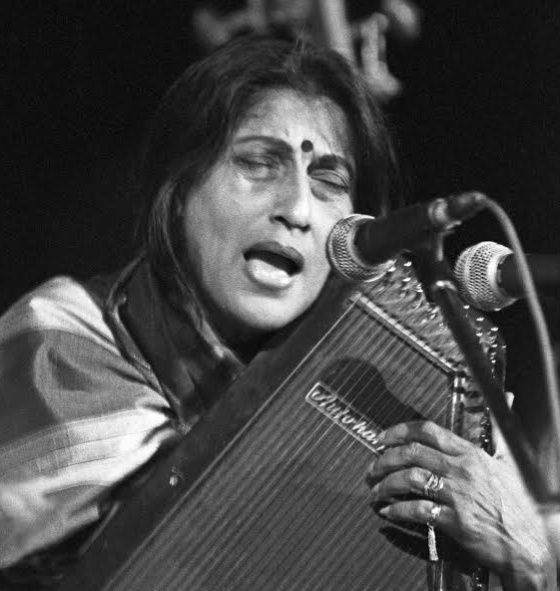

'Anyone who heard her sing was left with a lump in the throat.'

Sunita Budhiraja recounts her encounters with the Goddess of Swara.

'She became one with the universe while she sang and no longer remained Kishori Amonkar.'

Photograph: Kind courtesy Shobha Deepak Singh

Kishori Amonkar's singing always left me numb.

I have listened to her music for more than four decades and it has never happened that I was not transported to a different world.

In fact, anyone who heard her sing in person was left with a lump in the throat.

Amonkar was one artiste for whom I compered several concerts, yet I never came in her personal radar unlike most other artistes who I got to know personally.

Kishoritai, as most of her fans addressed her, had an aura of her own that served as a boundary wall and restricted people from coming too close to her.

She neither talked to anyone before the concert in the green rooms nor did she like meeting people after the concert. She was tuning herself with her tanpura, as she would say.

But she did notice me every time I compered for her and commented, 'Who is this lady? She speaks so well,' and then surrendered herself to her swaras.

I was fortunate to compere her programmes in different cities and, each time, I received this one-liner as appreciation.

Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia says of his flute: 'I have to tune myself as the flute cannot be tuned because it does not have strings. It is just a dead piece of bamboo that comes to life with the wind, the wind of my breath, so it is important that I am tuned with myself.'

Amonkar, too, concentrated more on tuning herself than her tanpuras. And that is the time she became one with herself.

After her concerts, she was in a different world; she was already transported to a stage where even the audience felt one with god.

Those who may never have believed in the supreme power would feel there was something inexplicable about what they just experienced.

I vividly recall an incident when she came straight to her seat without offering flowers to Swami Haridas's picture and started tuning her surmandal.

Shrigopal Goswami asked her: 'You should have offered flowers to Swami Haridas's photograph.'

Pat came her response, 'Today, I will not sing; Swami Haridas will sing through me.'

When the concert began, everyone among the 2,000-odd audience felt the presence of Swami Haridas.

My first chance to meet Amonkar was in Vrindavan, where she was invited almost every year by Acharya Shrigopal Goswami to perform in the Swami Haridas Music Festival of which I was the anchor for several decades.

She would be there to sing to the thousands of her fans who travelled from all over the country to listen to her soulful renditions.

Vrindavan being the bhoomi of Krishna, her music united the audience with the Lord.

She became one with the universe while she sang and no longer remained Kishori Amonkar.

Impeccably dressed in a plain, elegant sari with a zari border, she covered her head with the pallu and holding her surmandal, Amonkar would begin her recital around 4 am to a packed house and go on till after sunrise.

First she would offer her prayers in front of the huge photograph of Swami Haridas and then she would take her seat for the performance.

She truly believed in the prahar system and never deviated from that in the selection of her ragas. Hence, we were privileged to hear ragas that we would usually not listen to because most other music programmes did not last as long.

These included Lalit, Abhogi, Alhaiya Bilaval, Bhairav, Nat Bharav, Adana, Bhairavi and so on.

In between she would sing a Meera, Surdas or Kabir bhajan.

Regardless of what she sang, the pandal would be filled with unprecedented sublimity and, by the time she concluded, every eye would be moist.

She would fold her hands in namaskar to the audience and suddenly get up and leave without uttering a word.

I vividly recall an incident when she came straight to her seat without offering flowers to Swami Haridas's picture and started tuning her surmandal.

Shrigopal Goswami asked her: 'You should have offered flowers to Swami Haridas's photograph.'

Pat came her response, 'Today, I will not sing; Swami Haridas will sing through me.'

When the concert began, everyone among the 2,000-odd audience felt the presence of Swami Haridas.

I am tempted to quote Pandit Jasraj in the context of Amonkar. This will give some insight into the qualities of both the legendary artistes.

The other day he and I were conversing about various artistes who have touched his life. Amonkar was one of them.

While both the artistes had heard about each other earlier, they first got to meet in person in 1966 in Nagpur.

Pandit Jasraj recalls that, during a recital, Amonkar came and sat in the front row. As soon as he concluded the rendition in Darbari Kanada, she gestured that she had to leave. On his insistence, she sat till the end.

The audience was edgy.

Pandit Jasraj told her, 'You better go to the stage and begin the concert otherwise I will lift you and carry you in my arms.'

She said, 'Okay, do that.'

And Pandit Jasraj actually carried her in his arms to the stage and made her start singing.

The next day, Pandit Jasraj had booked a trunk call (these were the pre-STD days) and went for Amonkar's programme, having given instructions that he should be informed if the call came through.

While Amonkar was singing, he was told that the call was connected and he stood up to leave. Amokar saw this and stopped singing and said, 'Jasraj bhai, just five minutes.'

Of course, Pandit Jasraj stayed back.

The two were once performing on the birthday of Appasaheb Jalgaonkar, the harmonium maestro.

Amonkar had to give her recital first, but went on tuning her tanpura for over half an hour. The audience was edgy.

Pandit Jasraj told her, 'You better go to the stage and begin the concert otherwise I will lift you and carry you in my arms.'

She said, 'Okay, do that.'

And Pandit Jasraj actually carried Amonkar in his arms to the stage and made her start singing.

Her guru and mother Mogubai Kurdikar, a renowned vocalist of her times, lost her cool when she learnt that Amonkar had sung for a film, the title song of V Shantaram's Geet Gaaya Pattharon Ne.

Mogubai told Amonkar, 'You should not touch my tanpuras if you are going to sing for films!'

Amonkar lost her voice when she was 25.

She came in contact with Sant Sardeshmukh Maharaj in Pune who treated her and her voice miraculously came back.

She felt the overpowering presence of her gurus and Raghvendra Swamy in whom she believed and prayed.

That was the reason she was quietly in commune with her audience, for she felt that Raghvendra Swamy was in each person sitting in front of her and she was singing for her gurus.

Amonkar felt closeness to god. Everything she sang became a prayer.

At the Swami Haridas festival in Vrindavan, the custom has been that all the artistes who perform in the evening offer obeisance to Swami Haridas at his samadhi in Nidhivan the next morning.

Amonkar's recital concluded around 8.30 am, much after sunrise.

The time given for the Nidhivan programme was 10.30 am.

Shrigopal Goswami, who was also the priest of the Banke Bihari temple, thought that all the artistes would be late.

As I reached Nidhivan, what I witnessed was Amonkar sitting on the floor right next to the samadhi with a surmandal in her lap singing without the mic: 'Mharo Pranam. Banke Bihariji. Mharo Pranam.'

A sadhu was accompanying her on the tabla. No musical audience.

In attendance were bhakts who were visiting Nidhivan, shedding tears.

And those infamous monkeys of Nidhivan, known to snatch spectacles and bags of visitors, were for once not creating a ruckus and quietly sitting on the floor too, as if listening to Amonkar's bhajans.

DON'T MISS reading the features in the RELATED LINKS below...

© 2025

© 2025