She lived for two-thirds of her life in India, adopted its national cause and customs, and took an Indian passport.

She served a prison sentence in Lahore as part of Gandhi's protests against an Imperial power which happened to be her motherland.

Freda Bedi delighted in confounding accepted definitions of identity.

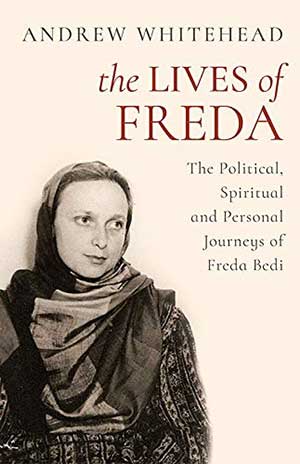

An engaging excerpt from Andrew Whitehead's The Lives Of Freda: The Political, Spiritual And Personal Journeys Of Freda Bedi.

When Freda Houlston confided that she was going to marry the handsome Sikh student she'd been seeing, her best friend, Barbara Castle, replied: 'Well, thank goodness. Now at least you won't become a suburban housewife!'

Freda's mother was exactly that -- a housewife in the suburbs of Derby in the English Midlands.

It would have been natural, expected indeed, for her daughter to fall into that same groove.

In fact, Freda refused to fit into any groove.

She broke the mould -- not once, but repeatedly through the decades.

In a world where issues of identity -- bound up in race, gender, religion and nationality -- loom so large, the manner in which she crossed these boundaries speaks directly to us today.

'It was my destiny to go to India,' Freda declared.

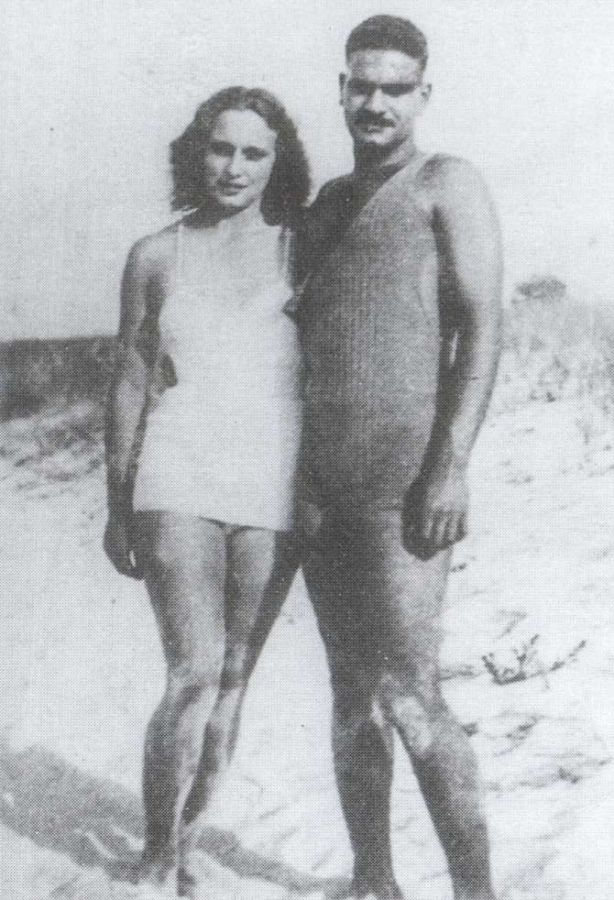

And from the moment of her marriage to B P L Bedi at a registry office in Oxford in the summer of 1933, she regarded herself as Indian and adopted Indian dress.

It would be another year or more before she set foot on Indian soil.

By the time she disembarked at Bombay, 23 years old and with her baby son in her arms, she had already co-edited with her husband four volumes about the country she was to make her home.

She lived for two-thirds of her life in India, adopted its national cause and customs, and took an Indian passport.

She served a prison sentence in Lahore as part of Gandhi's protests against an Imperial power which happened to be her motherland.

She was an English champion of Indian nationalism.

Freda Bedi delighted in confounding accepted definitions of identity.

She could not easily be categorised and saw no reason why she should be.

'One day she was standing in the Lahore Post Office buying stamps,' said her publishers.

'An American looked at her blue eyes and Punjabi dress, and his curiosity broke the bonds of formality.

Walking up to her, he asked: "Excuse me, are you English?"

She smiled and said: "I am -- and I am not."'

Her spiritual journey was as profound and remarkable.

She was church-going as a youngster, but by the time she enrolled at St Hugh's College, Oxford, in 1929, she no longer regarded herself as a Christian and never returned to the faith she was born into.

She encountered Buddhism in Burma in her early forties, and a few years later her endeavours to help Tibetan refugees marked her most intense moment of illumination.

The solace she found in Tibetan Buddhism emboldened her to enrol, in the mid-1960s when such adventures in Eastern religions were rare for Western women, as a novice nun.

A few years later, she took full ordination -- the first Western woman to do so in Tibetan Buddhism, and quite possibly the first woman in the Tibetan tradition ever to receive this higher level of initiation.

She went on to perform two remarkable services which helped Tibetan Buddhists adapt to exile -- recognising and meeting the need to educate young incarnate lamas, giving them the skills and confidence to find new audiences; and persuading her guru, the 16th Karmapa Lama, one of the highest Tibetan lamas, to make a pioneering rock star-style tour of the West in 1974 to spread Buddhist teachings and accompanying him on this five-month peregrination across North America and Europe.

Throughout her life, Freda constantly reinvented herself.

There was a restless, questing, aspect to her alongside the discipline and compassion.

She was a woman of faith -- but one who was an active leftist before alighting on the religion which came to define her.

She must have been rare among nuns in once having drilled, rifle on her shoulder, in a people's militia.

Yet the three big ruptures of her life -- from a provincial town to a women's college at Oxford University, from England to India, and from welfare work to ordination as a nun -- were not a repudiation of her past.

Thirty years after she left Derby, girls at her old school were collecting money for a new school Freda was setting up in the Himalayan foothills for young Tibetan lamas.

Her best friends at Oxford remained in touch all her life, even once she was in holy orders.

While wearing the maroon robes of a nun and with her head shaved, visitors sometimes commented how quintessentially English she still seemed.

Her life was shaped by two tragic deaths -- that of her father on the First World War battlefields, and of her second child while still a baby when Freda had lived less than two years in India.

There was an emotional vulnerability evident from her childhood onwards.

And a steely determination too -- once she had decided on a course of action, she saw it through.

Freda and Bedi's marriage was a heart-warming, insurgent romance, a defiance of convention, and an intellectual and political collaboration.

The couple were, in Freda's life-affirming words, 'two students in love, refusing to recognise the barriers of race and colour, dissolving their religious differences into a belief in a common Good, united in their love of justice and freedom... a marriage based on everything that was good in us.'

But it wasn't always an easy marriage.

Her husband was, in the arresting phrase of their US resident daughter, 'a chick magnet' -- and the issues within Freda's marriage must have had some influence on her pursuit of a spiritual life, taking vows which required celibacy as well as meditation and renunciation.

I had come across mention of Freda Bedi while delving into the story of Kashmiri nationalism and had met a handful of people with vivid memories of her.

As I found out more about her, the parallels with my own life captured my attention: From a northern grammar school to Oxford; on the left; married to an Indian; with India-born children; and deeply engaged with Kashmir and its troubled politics.

There are plenty of points of contrast too -- in particular, I am not a Buddhist -- but the manner in which Freda moved comfortably across those frosted barriers of race and nation, and identified herself so completely with her adopted country and culture, galvanised my interest.

This is not simply a story of how Freda Bedi became a Buddhist nun, and what she did while wearing those maroon robes; her earlier life is not recounted here simply as a prelude to a pre-ordained vocation.

This is a life story which explores the personal, the political and the immersion in India, as well as that last spiritual arc of her life.

This would be a much lesser book without the encouragement of the Bedi family -- their willingness to talk openly about their parents, and to allow access to their remarkable archive of letters, documents and photographs.

All three of Freda's surviving children -- Ranga, Kabir and Gulhima -- are fiercely proud of their mother.

Ranga Bedi, the oldest by more than a decade, kept in touch with many of his parents's old friends.

Kabir Bedi, a big figure in cinema and TV, at one time intended to make a film about his mother.

So they have been purposeful in assembling a family archive -- much more than a biographer has any reason to expect.

A collection of letters received is always helpful -- a series of letters sent is a rare and invaluable bonus.

Towards the close of her life, Olive Chandler, one of Freda's Oxford friends, gave to the Bedi family a lovingly kept file of letters, postcards, and Bedi family newsletters received over almost half-a-century -- an extraordinary window on a remarkable life.

'You do know about the recordings?' Kabir Bedi asked as I was taking my leave after my initial interview with him about his parents.

I didn't.

A year or two before she died, Sister Palmo -- as she was then known -- came to visit Ranga and his family in Calcutta.

She had bought a cassette recorder and used this to make a series of recordings reflecting particularly on the first thirty years of her life.

She made extensive notes, which the family still has, and then talked directly into the microphone -- haltingly at first, and then with increasing fluency and intimacy as she got into her stride.

These tapes were made, no doubt, for her family -- to satisfy their curiosity about her personal story.

As you might expect of a nun in her sixties looking back over her life with her grandchildren in mind, her recorded memories tended to privilege the spiritual over the political and to gloss over the episodes of personal anguish.

Nevertheless, these tapes stretching over several hours have informed this biography more than any other source of information.

They provide an intimacy, a closeness of contact, which would otherwise be inconceivable.

They also offer an answer to questions that inevitably worry the biographer: Did Freda keep a regional accent, for instance? (She didn't.)

While two of Freda's closest Oxford friends became household names in Britain -- Olive Shapley as a much loved broadcaster and Barbara Castle as the most successful woman politician of her era -- she is not as widely celebrated.

Indeed in the country of her birth, she remains an unfamiliar name.

In India, she was a friend and colleague of such towering figures as Jawaharlal Nehru and Kashmir's Sheikh Abdullah and a confidante of Nehru's daughter, Indira Gandhi.

She features in a group photograph taken in 1945 which includes three future prime ministers of India and two of Indian Kashmir.

But here too, the range of her endeavour and influence is largely unacknowledged.

Freda Bedi demands a biography not so much because of her fame, or the big jobs she held, or her political impact or institutional legacy, but because of the way she lived her life.

She was no saint and never pretended to be, and at times she made difficult decisions which hurt those around her.

She constantly crossed borders -- not simply national borders, but also those less tangible lines which divide on the basis of faith, ethnicity and sex.

In Freda's lifetime, these lines were more deeply etched than they are today -- but they remain deep social and political fault lines, and for those who wish to bridge them, Freda's life and achievements are astonishing, indeed inspiring.

Excerpted from The Lives Of Freda: The Political, Spiritual And Personal Journeys Of Freda Bedi by Andrew Whitehead, with the kind permission of the publishers, Speaking Tiger Publishing Pvt Ltd.

© 2025

© 2025