'If Ruttie had been alive, Jinnah would never have turned communal.'

Veenu Sandhu checks out Mr and Mrs Jinnah: The Marriage That Shook India.

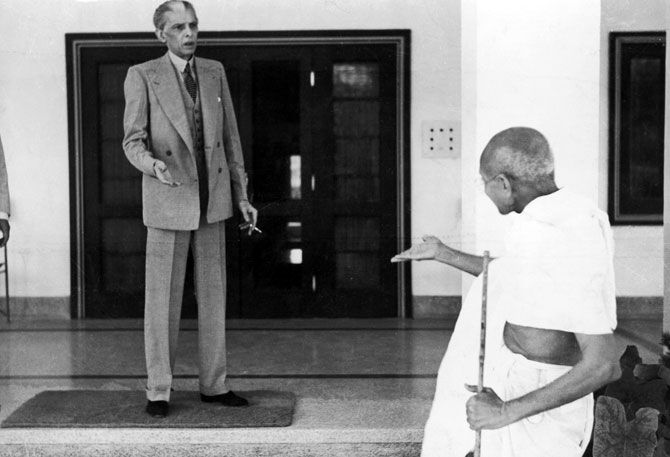

Of all the stalwarts of India's freedom movement, the one who remains largely an enigma is Mohammad Ali Jinnah.

A reserved, self-made man whose life followed a carefully laid out plan, Jinnah is often described as a cold rationalist who went from being an ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity to one who would execute the British policy of 'Divide and Rule' in the most extreme form: Partition.

The reasons and the circumstances that brought about this acute transformation, however, remain as indecipherable as the man himself.

Could it, in some way, have been the destructive manifestation of his struggle to cope with a personal and emotionally devastating tragedy: The decay and subsequent death of a relationship he had never planned but which eventually consumed him, though he never let that turmoil reveal itself to others?

Towards the end of her book, Mr and Mrs Jinnah: The Marriage That Shook India, journalist Sheela Reddy hints that this perhaps was the major trigger that changed the man.

'If Ruttie had been alive, Kanji was convinced, Jinnah would never have turned communal,' Reddy writes.

Reformer, politician, writer Kanji Dwarkadas was a close friend of Jinnah and his wife, Ruttie Petit, a woman Jinnah fell in love with when she was 16 and he 40.

Smitten by him as he was by her, they married two years later in what was described as the 'worst mismatch in recent times' -- not just because of the yawning age gap.

She was Parsi, the only daughter of a baronet and a rich society girl.

He was Muslim and had been an unemployed, struggling young lawyer who lived in a small hotel room when he first came to Bombay (now Mumbai).

His surplus confidence and natural sense of superiority would quickly take him up the social, legal and political ladder.

Reddy's book came about as accidentally as the Jinnah-Petit romance when she stumbled upon some private letters written by Petit.

The letters were preserved at Delhi's Nehru Memorial Museum and Library by Padmaja and Leilamani Naidu, daughters of Sarojini Naidu and Petit's closest friends.

More such intimate exchanges -- between the Naidu family and from the two sisters to Petit -- form the key source material of this well-documented, even if dramatically written, book. But then, drama is at the very core of this magnificent tragedy.

Reddy has done well to put judgment aside and tell the story as she saw it, often piecing together the narrative from whatever material she could gather during her research that took her to Delhi, Mumbai and Pakistan, graphically recreating the situations in her mind.

The character that stands out is Petit -- feisty, rebellious, young and, like Jinnah, a nationalist at heart.

She goes on to become a woman desperate to break free from playing wife and mother, and tormented by what she perceives as the indifference of the 'cold logician' she has married and who is now maniacally busy with politics.

Her scandalous marriage to Jinnah has already left her lonely, cut off from her family and the Parsi community.

But she is fearless, at least in the initial days. So much so, that when her father seeks an injunction in court, accusing Jinnah of trying to abduct his daughter for her fortune, she happily says in court: 'Mr Jinnah has not abducted me, it is I who have abducted him.'

At another time, instead of a courtesy, she chooses to greet the viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, with a namaste.

When he tells her that when in Rome, she should do as the Romans do if she didn't want to jeopardise her husband's political future, she coolly replies, 'That's exactly what I did. In India, I greeted you the Indian way.'

It is tragic to see this sparkly personality, a stunning beauty of her time, sink into shadows and her playful teasing of Jinnah, whom she refers to as 'J' in her letters, become vicious and aimed at provoking and annoying him.

If she gets under his skin, which she did as Jinnah in a rare moment reveals -- 'Ruttie drove me mad' -- he doesn't show it to her and that provokes her to trouble him more.

She would walk into his chambers when he would be in a conference, sit on the table dangling her legs, making the men in the room distinctly uncomfortable. Jinnah would pretend not to notice her and continue with his business.

He would go about his unyielding routine, while she sought solace in sleeping pills, theosophy and the occult.

Later, she would turn to jazz and dance the night away with other men at the Taj.

If she did this to catch Jinnah's attention, she failed. He wouldn't react.

The book thankfully does not get into finding faults or pinning blame on either. It stays neutral, maintaining a careful balance, concerned with just telling the tale.

But Reddy does, again through letters by Sarojini and Padmaja Naidu, point to the tiny soul, their daughter Dina, who suffers hopeless indifference as Jinnah and Petit deal with their lives and themselves.

She is left almost forgotten in the nursery.

Petit, whose heart aches for her cats, appears to feel nothing for the baby, leaving her and taking off to Hyderabad when she is barely four months old.

So much so that, in a letter to Leilamani, Padmaja writes, 'I simply cannot understand Ruttie's attitude -- I do not blame her as most people here seem to do, but whenever I remember the little, dazed, scared child, like some mortally hurt animal, I come very near hating Ruttie in spite of my great affection for her.'

Their mother, Sarojini Naidu, is less forgiving of Petit, whom she loves dearly, as she writes, 'I could beat Ruttie whenever I think of that child.'

The transformation of Petit, as of Jinnah, is stark.

The woman who once enjoyed politics and who was 'filled with excitement at the prospect of listening to three days of long speeches' when she set out to attend her first Congress session, makes the trip with Jinnah to attend the year-end sessions of the Congress and the Muslim League in Amritsar in December 1919 with a dull, listless heart.

'Let me be free. Let me be free,' she writes at one point and, when she finally does break free, she is determined not to go back again 'under this marriage ice'.

Not only is Reddy's research thorough, she tells a compelling story.

If there is one thing missing from the book, it is Jinnah's voice.

Unlike Petit and the Naidus, all of them voracious letter writers, Jinnah hardly wrote letters and, when he did, he kept them impersonal. This is why words such as 'perhaps', 'maybe', 'probably', 'presumably' are used often to recount situations involving him or his state of mind.

Striving, as a researcher ought to, Reddy tries to scale this hurdle too, with some success.

She manages to find a small window into his mind in Frederick Masson's book, Napoleon: Lover and Husband.

Underlined by Jinnah, 'over and over again in curly and straight lines,' are these three words from the book: 'Reproaches are senseless.'

But there comes a moment when Jinnah's emotions briefly get the better of his stoic reserve.

At Petit's funeral -- she dies on her 29th birthday, a death many believe she deliberately invited by overdosing on morphine -- when called as the nearest relative to be the first to throw earth on her grave, he suddenly breaks down and sobs like a child.

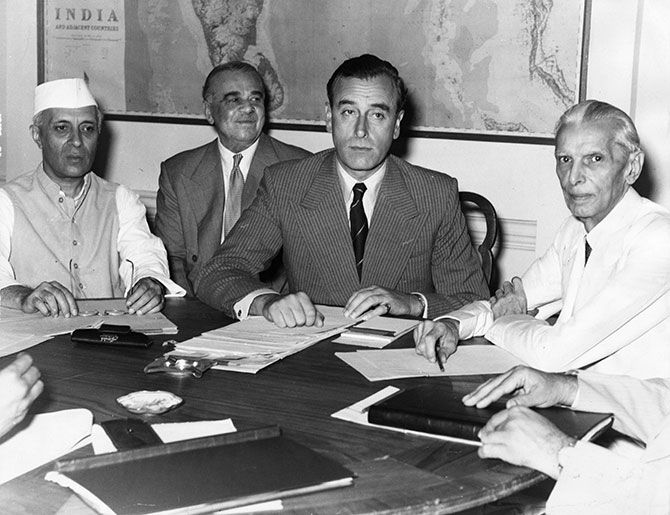

The 'cold logician' would soon after lock all his emotions firmly in his heart and again plunge himself into politics.

And where Petit once stood by his side like a breath of fresh air, would stand his sister, Fatima, 'enjoying his diatribes against the Hindus,' as Kanji is quoted in the book, 'injecting an extra dose of venom into them.'

© 2025

© 2025