Suddenly the sands are shifting and even friends are acting strange, notes Aditi Phadnis..

In a Delhi suburb, owners of a restaurant called Yummy Bhutan (where, by the way, you can get 'very tasty Chinese food') could be echoing China's sentiments.

Yummy Bhutan is exactly how China is looking at Bhutan. And India has made it quite clear that it doesn't like it.

To misquote Princess Diana ('There were three of us in this marriage, so it was a bit crowded'), there are three in the Doklam standoff -- India, Bhutan and China.

The postures are such that South Asia has been plunged into acute anxiety and tension. Worse, there are indications that the Great Game is being played out again.

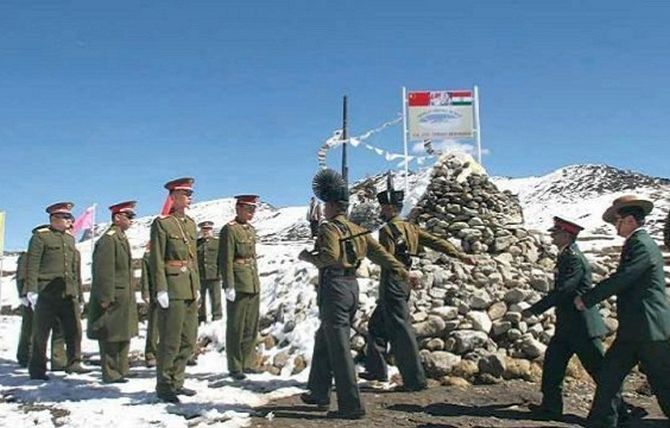

Like all tensions, it began with boundary and land: 14 countries have land borders with China -- Russia, Mongolia, North Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, India, Bhutan, Nepal, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

Because of its colonial history, China had territorial disputes with all of them. It has settled its land boundaries with all its neighbours -- barring India and Bhutan.

So what do the disputes involve?

With Bhutan, it is a matter of 764 sq km of territory.

Beijing claims 495 sq km of territory in the Jakurlung and Pasamlung Valleys in north-central Bhutan and another 269 sq km in western Bhutan, comprising the Doklam Plateau.

Doklam Plateau abuts the Chumbi Valley, which, like Tawang on Bhutan's eastern border, has enormous strategic significance for China, Bhutan as well as India.

If China gets hold of this territory, the military advantage in India's Northeast might as well be lost to China.

But that's not all.

The understanding between Bhutan and India is that their border disputes are to be settled together, not piecemeal as there is an intrinsic strategic linkage between the two in the Chumbi Valley.

By annexing the Doklam sector, the Chinese People's Liberation Army will widen the eastern shoulder of the Chumbi Valley and with the road extension, achieve significant operational and logistical flexibility for a military strike through the Chumbi Valley towards the Siliguri corridor.

Bhutan is China's only neighbour that Beijing does not have official diplomatic relations with.

This suits India fine.

In 1949, Bhutan signed the Treaty of Perpetual Peace and Friendship with India, under which it agreed 'to be guided by the advice of the Government of India in regard to its external relations'.

This has underwritten India's advisory role in Bhutan's foreign policy making, including relations with China.

The India-Bhutan Friendship Treaty, which replaced the 1949 Treaty, in 2007, does not require Thimphu to be guided by Indian advice on foreign policy matters.

It only requires them to 'cooperate closely... on issues relating to their national interests'.

China views India's treatment of Bhutan as a 'protectorate' abhorrent.

But there are legitimate reasons for Bhutan's fear of China.

It watched with silent horror the crushing of the Tibet uprising in 1959, the punishment meted out to followers of Buddhism and the vigorous implementation of a classless society in China.

Bhutan has its own ruling elite. Its monastic estates, and estates belonging to the handful of nobility -- the Drukpa -- were worked by tenured serfs and slaves.

Socialism, much less Communism, does not come naturally to it. And it has just about managed to cope with a refugee problem: With the Nepalese for instance.

It certainly does not want hordes of Tibetan refugees to come streaming into Bhutan.

Like all other countries, Bhutan is changing.

Guided democracy introduced in 2008 has put down shallow roots. But because of this, there are people who question Bhutan's almost blind allegiance to India and argue that third country domination in Sino-Bhutan relations (such as they are) is not desirable.

The signals of the changes were first out there for everyone to see when Jigmi Thinley, Bhutan's first prime minister, met then Chinese premier Wen Jiabao on the sidelines of the climate summit at Rio de Janeiro in Brazil in June 2013.

India was kept out of the loop.

An official People's Republic of China release quoted Thinley as saying Bhutan wished 'to forge formal diplomatic ties with China as soon as possible.'

China responded with a statement that it was ready to settle the border issue with Bhutan.

After initial consternation, India's response was ruthless and swift -- and very visible.

Loans were held back and vehicle imports from India to Bhutan were stopped.

Kerosene and LPG subsidies were held back.

All this only strengthened China's resolve to do something about the situation.

Phunchok Stobdan, former ambassador and expert on Asian affairs, says the tension in Doklam should be seen in a wider perspective.

"A solution to this would be back-channel talks," he says. "I don't see any real threat of a war. India should increasingly look to strengthen its borders, especially make sure that there is no incursion into Siliguri."

But the bellicosity of the Chinese official media and its bureaucracy seems calculated to escalate tensions.

Says former Indian ambassador to China Nirupama Rao, "The dispute in the Doklam area is known. It is not a new phenomenon. But China's road construction is a deliberate move to trigger a response from Bhutan and from India."

"Through its actions, China seeks to impose its own definition of the tri-junction point of the boundary between Bhutan, China and India (Sikkim). The move has serious security ramifications for both Bhutan and India's defence interests."

Most professional diplomats counsel prudence, ironically, when for the first time under Narendra Modi India has somewhat ostentatiously tried to demonstrate that it can stand up to China (remember the toothache remark when President Xi Jinping visited Gujarat in 2014?).

On the other hand, almost all experts say that the standoff in Doklam is not a one-off event.

Says R S Kalha, former foreign service officer and China expert, "In my experience of dealing with the Chinese for over 15 years, including leading the Indian side for the crucial boundary sub group, I have never experienced that the Chinese PLA takes steps without approval."

So what are India and China going to do?

Already there are signs that both sides are stepping back from the brink.

A statement by a Chinese foreign ministry spokesman says the Mansarovar Yatra of Indian pilgrims, which was halted because of action 'of India soldiers on Chinese soil', could be reconsidered via another route.

The Indian foreign office is imploring journalists, experts and anyone who will listen that bellicosity and aggression will achieve nothing: Professionals are on the job of defusing tensions and they should be allowed to do their work unhindered.

But this is not a WWF match where the outcome is known to everyone.

Suddenly the sands are shifting and even friends are acting strange.

Ancient words of wisdom might work best here: 'When in doubt, don't.'

© 2025

© 2025