| « Back to article | Print this article |

Bagmati river: From holy river to flowing filth

Dinesh Kumar Mishra highlights the challenges faced by the much abused Bangmati River in Bihar because of solid waste, industrial effluents, encroachment and rampant construction along the river's banks.

"Dirty water of the Riga Sugar Mill is let into the Bagmati and the result is that ground water in a five-mile stretch (of the river) has become so polluted that even the cattle refuse to drink it. If the government could restrict the mill from discharging the effluent into the Bagmati, the lot of the people would improve."

That was Damodar Jha, member of Legislative Assembly, making a point in the Bihar Legislative Assembly back on March 1, 1955.

He repeated his remarks in the budget session of the state (March 29, 1955), saying, "Last year, the sub-divisional officer, after inquiry ordered the mill not to discharge effluent into the river from the next year, as it was too late then. This year, despite the order, the mill has released the effluent into the river and there is nobody to check it."

That was 57 years ago. Nobody checks it even in 2012. That is the story of Kala Pani in Sitamarhi district of Bihar. Unlike the Kala Pani of the British days, where Indian revolutionaries were put under solitary confinement, this is an open air 'jail' where food is at stake, drinking water is not potable, the air stinks, and health condition of the inhabitants is deplorable and local employment absent.

The problem aggravates

The problem aggravates

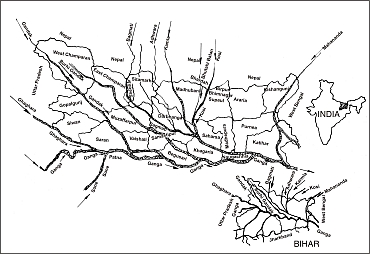

The Bagmati, on whose banks is located the capital of Nepal -- Kathmandu, enters Bihar in Sitamarhi district near Dheng (Figure 1). This river joins the Kosi near Badlaghat in Khagaria after traversing a distance of nearly 260 km on the Indian side.

The river, formerly adored as a holy source of salvation with unparallel nutrient water quality, has turned to a cesspool in Kathmandu. Still, clear water flows in the river as it disgorges near Nunthar in Nepal.

Embankments were constructed on either side of the Bagmati in 1970s from Dheng to Runni Saidpur in Sitamarhi over a length of 70 km to provide protection against floods to some areas.

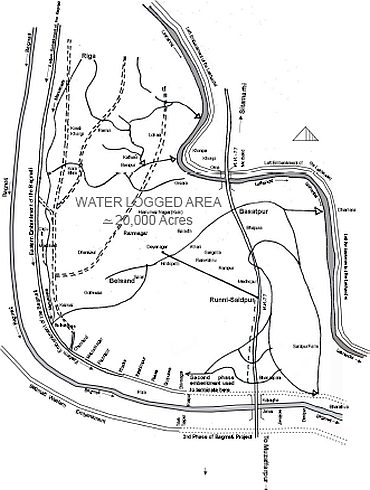

The left embankment of the Bagmati, however, sealed the mouth of one of its tributaries, Manusmara, also an abandoned channel of the Bagmati. Manusmara meets the Bagmati near Chandauli in Belsand block of Sitamarhi district these days (Figure 2).

The left embankment of the Bagmati, however, sealed the mouth of one of its tributaries, Manusmara, also an abandoned channel of the Bagmati. Manusmara meets the Bagmati near Chandauli in Belsand block of Sitamarhi district these days (Figure 2).

The embankment on the Bagmati was going to block the entry of the Manusmara into it. If unattended, the Manusmara waters would either backflow into the area protected by the Bagmati embankment or would start flowing parallel to the Bagmati's left embankment, flooding newer areas downstream.

Massive water-logging would follow in either case. There were only two options to deal with the situation:

- Construct embankments along the Manusmara till 20 km north so that the floodwaters of the Bagmati do not spill even through the Manusmara during floods.

This was a costly proposition and the rain water trapped between the Bagmati's left and the Manusmara's right embankment was going to get locked without any escape. Breaching of any of the embankments would have worsened the situation.

- Construct an anti-flood sluice at the confluence of the rivers operating it only when the water level in the Bagmati was lower than Manusmara. The engineers opted for the latter option and opined that temporary closure of the sluice gate during floods would never extend beyond 70 hours and the spread of floodwaters of the Manusmara would not exceed 1,600 hectares, and a depth of 1.25 metres.

With lowering of flood levels of any of the rivers, the Bagmati or the Lakhandei, the Manusmara water would escape into them and would be drained out during a three-day period, permanently water-logging only 480 hectares of farmland.

The sluice at Chandauli was completed in 2011, but until then, Manusmara's floodwater used to flow in the countryside at will and remained there round the year and the situation takes a turn for the worse during the rainy season.

Kala Pani knocks at the door

The Riga Sugar Mills Limited is located 10 km north of Sitamarhi at Riga, on the Sitamarhi-Dheng road. This factory was built in 1933 and has been discharging its effluent into the Manusmara ever since.

It used to be four to five times a year earlier, but now it is unchecked. Earlier, all the fishes in the stream would die when effluents were discharged, and the villagers 'filtered' them for their consumption, cursing the mill owners for the unfortunate occurring.

After the construction of the embankments on the Bagmati in 1970s, the situation turned for worse as polluted water of the Manusmara started spreading in the lower areas of the Belsand and Runni Saidpur blocks.

The area water-logged was thus covered slowly with water hyacinth, which rots after the rains are over, and the stink spreads all over the place. Effluents of the sugar mill added insult to injury and color of the water turned black.

The drinking water sources got polluted and agriculture around the areas was destroyed. Peoples' health went downhill, communication disturbed and local employment came to a grinding halt. Kala Pani, initially used as a joke, sadly became a reality.

Kala Pani reaches NHRC

A social worker of Sitamarhi, Dr Anand Kishore, took the matter with the National Human Rights Commission in 2000 and sought its intervention to correct the situation. Responding to NHRC's queries, the collector of Sitamarhi in his letter made startling revelations.

He observed that the RSML manufactured alcohol (spirit) using molasses as raw material, a by-product of sugar manufacturing. After the processing, the chemically-infested residue was left over as effluent. Citing the villagers he wrote that the polluted effluent was released every week into the river and all the nearby villages had started stinking.

Consumption of polluted water led to skin diseases and stomach troubles. Eating fish from the polluted water source led to diarrhea. Fish died when the effluent was dumped into the river.

Flies and mosquitoes menace prevailed all over. The residents told him that the water treatment plant (in the mill) did not have the adequate capacity and even that lesser capacity remained underutilised.

He contacted the vice president of the RSML who denied the allegations and maintained that the mill was equipped with adequate arrangements of treating and discharging the effluent. The collector was, however, not convinced.

He then contacted the member secretary of the Bihar State Pollution Control Board in Patna, to direct the RSML to install a plant of adequate capacity. He also wrote to the managing director of the RSML for the same.

The NHRC fixed October 27, 2003 for a hearing but by that time the collector had not received any communication from the BSPCB or RSML, who had not taken any action until then. The collector reminded the BSPCB once again on February 25, 2004 but with no results.

Bagmati embankment breach chokes Manusmara

Dr Kishore had moved the NHRC following a breach in the Bagmati's left embankment near Dhanakaul in 2000.

Emanating sediments that emerged with floodwaters after the breach, blocked the mouth of the Manusmara near Chandauli, and forced the Manusmara to take a turn towards the National Highway-77 on the east via some residential areas of various areas.

Another breach in the Bagmati embankment near Chandauli in 2004 filled up many other smaller drains, and that further worsened the situation.

After the breach at Chandauli was plugged in 2004, some more villages got covered by black water as the drainage routes had become shallow and narrow.

The Manusmara water had swept away the road bridge near Dharharawa. The government, instead of restoring the bridge, plugged the gap and whatever exit the floodwater had had, was blocked.

The Manusmara was forced to take a turn towards south and its course, devastated several villages.

Dissent simmers against the sugar mill

Water-logging, coupled with pollution had become a permanent feature now. With no respite in sight, the general secretary of a local organisation of flood victims -- Bagmati Baarh Pirit Sangharsh Samiti Ram Sevak Singh, gave an 11-point charter to the commissioner, demanding immediate installation of an effluent treatment plant at the RSML, and directing the mill to discharge only the treated effluent in the Manusmara, failing which, the incomplete left embankment on the Bagmati be demolished to facilitate drainage.

"The sugar mill was indifferent to our demands for rectification," said Singh.

"We met the science and technology minister in 2007. He was a member of legislative assembly from our area and after explaining our problem, he got samples of water from Kala Pani tested in some laboratory in Hyderabad. The report, however, said that the water was not polluted," he says.

"The minister assured us that he would still do something. I asked him who was more powerful -- the mill owner or the government? He shied away. Later, we submitted a detailed memorandum to the chief minister who visited this area in 2007 in connection with electioneering. Nothing happened," he adds.

"We raised the issue with another minister from our area, the collector of Sitamarhi and the secretary of the Water Resources Department a few years ago only to get assurances in return. All were convinced that the polluted water had its origin in the sugar mill but did nothing. By the government's own submission, nearly 22,000 acres of land is covered under a sheet of polluted water in Kala Pani," he says.

"Despite all this, the mill owners rule the roost with impunity. Our only source of livelihood, agriculture, is systematically snatched by the WRD and the RSML. Migration to greener pastures is the only way left to keep the body and the soul together," he adds.

Government takes cognisance

The government first appreciated the problem in 2000 that the Manusmara waters would have to be drained safely to solve the problem. The WRD made plans for draining the Kala Pani, but without touching the RSML.

It is yet to acknowledge that the RSML is responsible for this poisonous water. This scheme has not been implemented so far. Even if the drainage scheme is implemented, the water might disappear, but the toxicity would remain and wherever this water would go, the toxicity would follow.

As the situation stands today, 6,840 hectares of agricultural land in Kharif, 1,500 hectares in Rabi and 570 hectares in hot weather season, totalling 8,910 hectares has come under permanent water-logging against 480 hectares assessed by the WRD.

The value of the crop over this land was assessed at Rs 12.17 crore at 2001 prices. This would mean that the loss to agriculture alone in the past 11 years amounts to Rs 134 crore.

If so much of wealth is taken out of an area of nearly 9,000 hectares, the current state of its ruined economy and losses accrued over years can be well imagined. Some of these aspects can be priced, some can only be felt and the rest are simply immeasurable.

Tenders were floated for implementing the drainage scheme in November 2008 at an estimated cost of Rs 2.23 crore but the drains had to pass through the lands of the rayyats and they had to be compensated for.

Acquisition of land for such works is a lengthy and time consuming process. The executive engineer of the Drainage Division of the Bagmati Project requested the Mukhias of all the concerned panchayats to issue a no objection certificate to the government so that the work on the drainage could be expedited, with the government taking care of the compensation part of it.

He got it from the concerned Mukhias, but the villagers maintain that RSML discharges toxic effluent in the Manusmara, which pollutes water affecting adversely a large population. They demand that the treatment plant of the RSML be made functional and any effluent be discharged in the river only after it is processed.

Any digging of earth shall be permitted only when this is done. The executive engineer says, "Preventing the polluted water from getting into the river is not in the jurisdiction of this division and administrative support is required to achieve this, but no administrative support has come and the excavation work is held up."

Defiant sugar mill

It is interesting to note that the member secretary of the BSPCB had issued a show cause notice to the chairman, RSML in 2009, charging the mill of releasing toxic effluent the Manusmara and the suspension of the work due to people's resistance and threatened to take necessary steps against the unit.

The superintending engineer of the project had recommended action against the mill by a letter to the collector in October, 2009. The stalemate continues.

Now we come back to the point raised by Ram Tapan Singh as to who was more powerful -- the sugar mill or the government.

When the author asks the same question to Raghunath Jha, who has many times been an MLA,a member of Parliament, and a minister in whose constituency Kala Pani is partly located.

He says, "There is no power bigger than the state power but the chief minister will not go there to conduct an inquiry. It is altogether a different question as to how the authority vested in state is put to use. The mill owner is capable of managing everything; obviously he is more powerful than the government."

Hopes and apprehensions

Singh gives the update on the subject and says, "The Bihar government now says that it will execute the scheme under Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. This work should now be done but when will it be done is the question. We had written to the government for compensating the crop loss that our area has suffered because of water-logging and pollution over years. It has agreed in principle that it would compensate the losses according to the provisions of Calamity Relief Fund."

"It has identified 137 farmers, who had applied for compensation, for payment at Rs 15,000 per hectare for one year. Necessary clearances have been obtained and this and it is likely to be paid. One has to wait and watch when this is paid and what the base year is," he adds.

Nothing has happened until the time of writing this report.

It is time to act

Why should our entire establishment, our MLAs, our ministers, our laboratories, our WRD, our collectors, and our NHRC be so helpless before a private commercial institution? The state is prepared to compensate the farmers, nobody knows for how long and since when but it cannot touch the sugar mill probably because the mill is more powerful than the government.

There is no dearth of people beyond Kala Pani, however, who support the sugar mill. Bihar is not an industrial state, and if problems are created for the RSML, it will go against the interest of the estate.

The local sugarcane growers also have their stakes in the mill. It is likely that the government is taking cognisance of these facts and is soft on the mill. But if the government is so helpless, why doesn't it install a treatment plant in the sugar mill and run it at its own cost and save the farmers of Kala Pani?

This will, at least, save Rs 12.17 crore annually in terms of food production and spare the farmers of pollution that exists today. The government can waive off the capital and running cost of the treatment plant if it so likes or subsidise it.

There is no political will in the governments, at least, since 1955 to solve the problems of the people of Kala Pani and one does not know when and which government will respond to the peoples' demands. The other option is to fight it out through people's organisation but that is a tall order in a society that is fragmented.