From dating apps to events, the shrinking community is innovating ways to encourage the young to marry within the faith, reports Ranjita Ganesan.

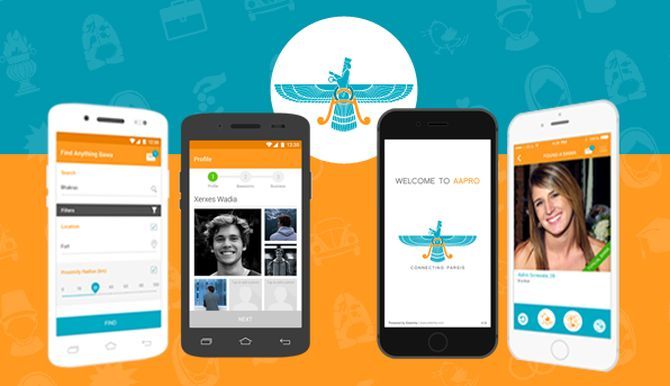

In the Aapro app, or “Tinder for Parsis” as it is better known, users can express interest by breaking an eedu (egg) on each other or sending across some gaar (abuse and insults).

The bawa community has so many unique characteristics and needs that it merits its own social network, say the creators of the platform, actor-model Viraf Phiroz Patel and Pune-based app developer Umeed Kothawala. Its beta version has some 2,000 users, and Patel often hears of young people using it to go on dates.

“The connections do not always work out, but nonetheless, connections are being made.”

This app is just one among several ongoing ideas -- both formal and informal -- that are aimed at encouraging Parsi-Zoroastrians to date and mate. The reason for this push includes a sharp decline in the community’s population.

Zoroastrians are a notified minority, according to the National Commission of Minorities Act 1992. The population fell from 1,14,900 in 1941 to 69,601 in 2001. In 2011, it fell further to 57,264. It would seem that an increase in population is not a thing India needs at all but the dwindling numbers of Parsis, known equally for their achievements and their eccentricities, jolted some researchers and the government.

Certainly, the most official of the population-revival efforts is Jiyo Parsi, launched in 2014, which entered its second phase this year.

Professor and director of Parzor Foundation, Shernaz Cama, who is spearheading the initiative, first sensed a decline in the early 2000s when she began travelling with a UNESCO team in Parsi settlements in Gujarat and the Deccan.

Mansions were lying empty and for days they did not see any children. Even in the Parsi baugs (colonies) of Mumbai, mostly elders gather in the gardens and clubhouses, while only a handful of tots are seen on the swings or football ground.

A significant part of the Parsi community is ageing -- over 31 per cent are elderly and only one in nine families have a child below the age of 10.

While religious beliefs -- inter-married Parsi women and their children are expelled from the community -- were believed to have caused most of the decline, researchers also found a tendency among Parsis to not marry or marry late and have one or no children had deeply affected demographic composition and fertility.

More than 30 per cent of Parsis were “never married.” If the total fertility ratio remains less than 1 (2.1 is required for a stable population), the community could be reduced to a tribe.

According to Cama, the responsibility to care for older dependents often affects these choices. Besides, as members of the community observe, if Parsis feel they cannot provide the best quality of life and education to their children, they opt not to have any. While Parsis are typically affluent, Cama says there are among them middle income couples who find it difficult to fund fertility treatments.

This is where Jiyo Parsi, an initiative by the minority affairs ministry, Parzor Foundation and Bombay Parsi Punchayet, among others, decided to step in with scientific intervention.

So far, through couples’ counselling, In vitro fertilisation treatments, appointments with gynaecologists and home visits, it claims to have resulted in the birth of 108 babies. This would mean a roughly 18 per cent increase in around three years. There are roughly 33 doctors helping in the process.

The team behind the effort now wants to go beyond just medical and financial assistance, and take the programme in the direction of advocacy and awareness. The hope is to instil pride among the youth for Parsi culture through more heritage walks, film screenings and workshops on subjects such as parenting.

The Jiyo Parsi programme’s otherwise sombre tone is also broken by its headline-grabbing advertisements. In its first phase, a set of colourful and controversial ads asked couples to “be responsible, don’t use a condom tonight” and told them “it’s time to break up with your mom”.

This time around, there are black-and-white ads that more urgently talk of the reasons why couples need to have children. The wisdom in these tends to sound like the advice often given by well-meaning older relatives across communities, and as such, is met with some rebuke.

The campaign suggests Parsis should marry when they are young, they must marry in order not to end up alone, they ought to have a baby early, and they ought to gift their child a sibling. The idea with both campaigns was to achieve maximum “virability” and that is happening, says adman Sam Balsara, chairman of Madison World.

The ads have received some criticism, he notes, “mainly from intermarried girls of the community.” One young girl, while calling the campaign interesting, told him that when she gets married is her business and nobody else’s. “It is a delicate issue,” says Balsara. “But nobody has given the Jiyo Parsi team the mandate to decide who is Parsi. Our limited objective is to get more Parsis to get married, and those who are married to have children.”

For those looking to marry, the fact remains that it is not always easy to meet fellow Parsis. Some groups have tried to make this process seem fun. Viraf Mehta, founding member of Zoroastrian Youth for the Next Generation, wants to change the view that the community is an ageing one. It led to the idea of an annual pin-up calendar, which, since 2011, has been showing off young, good-looking women and men of the community.

The group began in 2009 with the aim to help young Parsis meet each other through sports events, community service and social dos. Mehta says almost 40 romantic connections have been made so far, in a group of 4,000 members.

“We hear of quite a few success stories but people have ego when it comes to advertising a relationship. They don’t want to say they needed help to find someone,” says Mehta.

The Bombay Parsi Punchayet, too, organises some gatherings for the youth, advertised as “Nothing formal. They won’t even feel it’s a matrimonial meet.”

Of course, most of these efforts are restricted to Parsis. Jiyo Parsi’s social network for parenting advice and ZYNG’s Facebook page filter users from outside the community.

Perzen Patel, who runs the catering company Bawi Bride, says meeting Parsis is difficult but “not impossible”. She found her bawa groom through a family friend while studying in the United States.

She believes it is fair to offer assistance to couples with financial and medical difficulties because the Parsis rarely use any other government benefits or subsidies. “If I had problems conceiving, I would have used it.”

Shirin Mistry (name changed), a 28-year-old public relations professional, has been to several of ZYNG’s speed dating events. If you do not live in the community colonies, ZYNG events are the chosen way to connect with others of the faith, says Mistry. So far, the connections have not worked out.

“People of the same wavelength tend to not be in the country.” Mistry would like to pick a partner from among Parsis because of her respect for her religion. “It is one of the oldest in the world. Nobody wants to see it go extinct.”

Almost every birth is declared with fanfare in community publications. Advertising campaigns will not affect a big change, reckons Jehangir Patel, editor of the Parsiana magazine. In his view, the government initiative could have been treated as an opportunity to bring intermarried women and their children back into the fold, he adds.

“There will be many who will say that such a move would destroy the community, but if you weigh the pros and cons, it would be worth it.” The issue of intermarried women is a debate for the entire community to decide and act upon, says Jiyo Parsi’s Cama.

“It is beyond the remit of the Jiyo Parsi scheme or its team to change this definition.”