'Whether I die in Calcutta or in Paris, on a Wednesday or a Saturday, it does not matter, but you would not want me to come to India's door and then return to France without having visited India.'

'Either I will die or I will visit India!'

Claude Arpi hails Georges Clemenceau, French prime minister during the Great War, a great man who loved India.

More than 60 heads of states commemorated the 100th year of the end of World War I between the Allies and Germany.

A hundred years after the bitter war, German Chancellor Angela Merkel participated in the Armistice celebrations, perhaps because today there is no longer a victorious or defeated nation.

The entire world, including India, suffered too dearly between 1914 and 1918.

For what? Nobody is sure now.

The French daily Le Figaro explains the dichotomy: 'Commemorate means making choices.

French President Emmanuel Macron decided to go for a week-long 'memorial and territorial journey' through the different sites of the Great War.

For the French, the numerous functions were more than a celebration of a victory; there was a triple message in the event: One, to remember the poilus ('the unshaven ones') as the French soldiers were known during the War; to celebrate the capacity of the French nation to rebuild itself and finally, and perhaps most importantly, to promote a 'recast multilateralism'.

The presence in Paris on November 11 of the representatives of all those who participated in the War, including Germany, demonstrated this choice.

France has not forgotten India's participation in the War. Paris recently offered India a piece of land to construct the Indian Military Memorial for Indian troops at Villers Guislain, in northern France.

The memorial comprises a bronze Asoka emblem and a plaque honouring the Indian soldiers who died in the War.

But there is more to the relations between India and the War.

A Tiger among Politicians

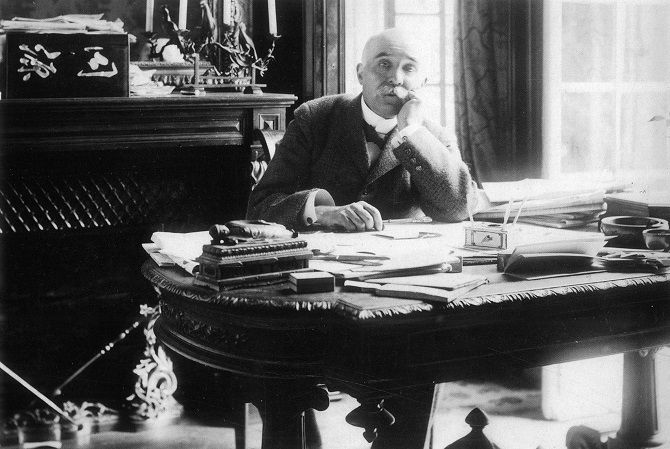

Whenever one thinks of the Great War, a name comes to mind: Georges Clemenceau.

Born in 1841 in Vendée, the hotbed of the monarchists during the French Revolution, Clemenceau came from a lineage of physicians. His father never really practiced, but he was attracted by political activism, following the Radicals, a party not enamoured of Catholicism.

Though a lifelong atheist, Clemenceau had an interest in religious matters from an early age. He joined politics as an anti-clerical, often fighting the French Catholic Church, strongly believing that that the Church and the State should strictly be kept separate.

From November 1917 to January 1920, he was the prime minister of France and played a central role in the Allies's victory.

He then became known as 'Père la Victoire' ('Father Victory') or 'le Tigre' ('The Tiger'), as he always favoured total victory over the German empire and militated for the restitution of Alsace-Lorraine to France.

In 1919, he became the main architect of the Treaty of Versailles at the Paris Peace Conference.

Clemenceau, the philosopher

There is another aspect to George Clemenceau: He was a great humanist, thinker, traveler and lover of India and its philosophies.

Mao once said: 'The philosophers have so far only interpreted the world, the point is to change it.' Clemenceau first changed the world by giving Victory to the Allies while being a philosopher at the same time.

This reminds me of Sir Francis Younghusband, the British 'imperial adventurer'. During his stay in Lhasa in 1904, he had become fond of the Ganden Tripa, the senior-most Tibetan Lama. In spite of the political difficulties and their personal backgrounds, they often sat together to discuss religion and philosophy. They developed a very close rapport. On his return to England, Sir Francis became a great adherent of the philosophy of Ahimsa.

But in Clemenceau's case, it was not a 'sudden conversion' as it was for Younghusband. He had spiritual inclinations from his early years in French politics.

In July 1885, he gave a speech in the French parliament: 'Inferior race, the Hindus? With this great refined civilisation that is lost in the mists of time!'

He also spoke of the Buddhist religion which later migrated from India to China, but left 'this great efflorescence of art of which we still witness today the magnificent remains.'

He would always remain fond of Buddhism.

The Guimet Museum

Clemenceau was involved in the creation of the Guimet Museum in Paris. He was close to Emile Guimet, a rich industrialist from Lyon who was passionate about Oriental religions. He traveled all over Asia and once back in France, he decided to create 'a didactic place dedicated to Buddhism, and, in general, to religions around the world'.

The Guimet Museum was inaugurated in Paris in 1889; Clemenceau even attended Buddhist ceremonies organised by the museum.

On February 21, 1891, when a puja in honor of the founder of the Shinshu sect was performed by two Japanese monks, Clemenceau sat in the front row.

A journalist asked the future French prime minister: 'Now, you can't stop us going to Mass?' Clemenceau quipped: 'What to do, I am a Buddhist!'

For him, Gautam Buddha was at the top of the thinkers' hierarchy; 'the greatest preacher of peace and fraternity that has appeared in the world'. Clemenceau called him the 'sublime monk' who preached the love of his neighbour and this without proclaiming the existence of an almighty God.

He greatly preferred Buddha to Jesus, probably due to the omnipresent Catholic Church in France at that time.

The Tiger also liked the fact that Buddhists did not proselytise.

In 1905, he told L'Aurore, a French newspaper: 'With what impatience do I wait for the day when we will see Buddhist and Shinto missionaries coming to Marseilles who will come and try to convert us!'

From 1917 to 1920, when he served as prime minister and war minister, he kept several statuettes of Bodhisattvas placed prominently on his desk.

Clemenceau the Traveler

Clemenceau knew it was not enough to read books about philosophy, he decided to immerse himself into the cultures he was studying.

Months after his retirement, at the age of 80, he embarked on a long journey to Egypt, Sudan, Ceylon, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Burma and finally India.

As soon as he arrived in Calcutta on December 5, 1920, he fell extremely sick; worried doctors advised his immediate repatriation to France.

The Tiger was not going to listen to the doctors: 'Whether I die in Calcutta or in Paris, on a Wednesday or a Saturday, it does not matter, but you would not want me to come to India's door and then return to France without having visited India. Either I will die or I will visit India!'

He recovered and went on a long journey in India starting by Benares.

He often wrote to his friend, the great Impressionist painter Claude Monet: 'I have come to Benares to take the most prodigious bath of light ... A large clear blue river, with an imposing curve of white palaces, which fades in the powder of dawn.'

He tried to attract Monet to India: 'If my name was Claude Monet, I would not like to die without having seen Benares.'

Clemeanceau wrote about 'a humanity crazy with expressive colors' which animates India.

'I do not want to go to heaven if Benares is not there,' he asserted, adding that even 'The incomprehensible cult of these sacred cows, coming in the morning to eat the flower mala s with which I was garlanded,' finds an explanation.

Clemenceau was very fond of Asoka, the king who renounced violence. 'The reign of the great Asoka is one of the purest human glories', he wrote, an antithesis of what Father Victory had been known for during the Great War.

Le Soir de la Pensée (The Evening of the Thought)

On his return from India, Clemenceau worked on his philosophical testament Le Soir de la Pensée, which shows not only his great erudition, but also his deep understanding of India's philosophical thought.

Several chapters mention India. One is entirely consecrated to The Philosophies of India. Clemenceau admitted having experienced a 'delicious joy' in discovering the Ramayana, the Vedas and the Buddhist scriptures.

He acknowledged that he had grasped only the superficial aspects of Indian Thought. 'I do not know by what excess of daring I try to summarise aspects and developments of the Hindu thought in a few lines. [But] this subject holds me and leads me.'

Elsewhere he says: 'By her Vedic hymns and her great poems, we find unexpected resemblances to Greece... The genial feature is that it does not formally reject any affirmation which could bring some doubt to the proclaimed belief.'

'The cosmogonies of India cannot be counted. All contradictions accumulate, without ever losing confidence, always ready to assimilate everything.'

A hundred years after the Armistice, this aspect of Father Victory should be remembered though his philosophical views never interfered in his political decisions as one of the main actors of the Great War.

Claude Arpi writes: I am grateful to my colleague Christine Devin for her numerous inputs to this feature.

© 2025

© 2025