Photographs: Alexander Natruskin/Reuters

On the 70th anniversary of World War II, the 88-year-old soldier, who also saw action in the 1971 war with Pakistan -- relives his memories of the war that remains the bloodiest conflict in history in a conversation with rediff.com's Archana Masih.

I was commissioned in 1943. After the initial grounding of four months in my regiment, I was earmarked to go to Burma. But before that I had to undergo three months of jungle training in Chhindwara in the Central Provinces, now Madhya Pradesh.

After those three months, we got the shock of our lives when we were told we had to proceed to Italy to join the First Battalion that had suffered very heavy casualties. Four of us were shipped to Italy.

Travel to Italy

We left Bombay by ship in March 1944. We went to Port Suez and took a train from there to Cairo to await our ship to Italy. We had to wait there for a month because there was no ship. We boarded a Polish cruise liner that had been converted into a troop ship. There were Indian soldiers going to the war aboard the ship.

We got off at Taranto at the heel of Italy and were sent to a transit camp. I was asked to be the assistant adjutant of the transit camp till I moved up to join my unit.

General (T B) Henderson Brooks, the famous general, was the second in command of that battalion. The British did not give him a promotion and command of the battalion because he was an Anglo Indian.

I met him at the transit camp and I will never forget the meeting. He told me: 'So you are D'Souza who will be going to join the First Battalion.' I said, 'Sir, I am fed up of waiting.' He said, 'My dear boy, you don't know what war is.'

I met him at the transit camp and I will never forget the meeting. He told me: 'So you are D'Souza who will be going to join the First Battalion.' I said, 'Sir, I am fed up of waiting.' He said, 'My dear boy, you don't know what war is.'

Eventually I got my orders and took a convoy of Indian troops from Taranto to Rome by train. From there we went by road to our various destinations.

The Impossible Bridge

I joined the battalion immediately after the third battle of Cassino in which my battalion took a very prominent part. The earlier two attacks on Monte Cassino had failed, so they decided to hand it over to the British 15th Army and selected the 8th Indian Division that was known as the River Crossing Division.

There were two divisions of the Polish army, a French brigade, Canadian tanks, British artillery to take Cassino. The 8th Indian Division was asked to form the bridgehead across the very fast flowing Gari river.

We sent two of our sepoys from Ratnagiri to swim across the river to check where we could launch the bridge. They came back with the information and our Indian engineers launched the bridge which was called the 'Impossible Bridge' because it was under direct observation of Monte Cassino.

Having got the bridge across, we made the bridgehead after which the Poles and the Free French went through, followed by the Canadian tanks. When the actual assault on Casino was launched by the Poles, we were told to go to a place called Piere Monte to prevent any German counter attack.

I joined the battalion immediately after that at the foot of Peruguia, a famous town in central Italy. From there we were asked to advance, I was allotted as a company officer to C Company commanded by a British tea planter from Assam, Jimmy Winter.

Here, I got a frantic message that the military transport officer of the battalion had been injured and I had to take over immediately from him. From there we were asked to advance along the hill on the main road from Rome to Florence. We fought against the retreating Germans up to the south bank of the Arno river which runs through Florence.

It was very hard fighting because the Germans fought a beautiful rearguard action. We were given 10 days rest. The Ghoums of the French army, who traveled with their wives in war, took over from us. I had to lead them on my motorcycle to take over from us.

Saving Botticelli's Venus

Image: A woman places flowers on the cenotaph at Martin Place in central SydneyPhotographs: Tim Wimborne/Reuters

On the first night I was told to check all the guards. I came across a Maratha soldier who was grinning and red in the face. I asked him 'Kai zala? (What's happened?)' He took me to the basement which had the art treasures of Florence. He was red in the face on seeing Botticelli's Venus.

When I reported this, the news went down the line. Who brought them there we don't know, maybe the Germans. Eric Linklater, the famous British writer who came down there, was amazed. The moment we found art treasures we posted a strong guard there. An old Italian professor who heard about it came and thanked us profusely.

Linklater also found the visitors's book of the Sitwell family with signatures of Karl Marx, the Pope and such famous people. As a mark of appreciation, he presented that visitors's book to us. He also said when peace came to Florence, the room in the Uffizi gallery, where Botticelli's Venus would be re-installed, should be called the Maratha room. Unfortunately, that didn't happen.

Breaching the Gothic Line

I was present for the battle when the Gothic line in central Italy was occupied by the Germans and we were the first battalion to clear them.

The company commander who led the battalion was an Anglo Indian major from Jabalpur. He launched a textbook attack. The Canadian tanks supported us and we captured the objective. That was the first dent that we made in the Gothic line.

The senior-most British officer said: 'I wish the king of England was here to see the battle, it is text book.'

I went up with the reorganisation squads and we captured German prisoners. One of them had a bayonet, I took it from him and still have it with me.

When President Clinton addressed the veterans of the Italian battles, he gave credit for piercing the Gothic line to the Nisei (second generation Japanese-American soldiers) division. I wrote a strong letter saying this is absolutely wrong, that we were the first to breach the Gothic Line. My letter was published.

We fought in tough terrain -- mountain ranges and rivers. We had to fight the cold, the rain, but the main enemy was the terrain. We crossed seven rivers. Our men were first class soldiers.

Removed from a White hospital for being Brown

In December 1944, we were told to move from the north of Florence to the Leaning Tower of Pisa because the American Negro division, which had just landed, had run across a very strong German patrol.

At one place the Germans saw us because the Indian troops were now famous. The Germans had left a man in the church tower. Each time he saw a collection of military vehicles he would ring the bell and they would open fire.

I had a battle accident here and was moved to an Indian casualty clearing station and then to a military hospital just outside Florence. It was dark so they could not see the colour of my skin.

In the morning there was a flurry of activity near my bed. It was a white South African hospital and within five minutes I was removed and flown to a British general hospital.

I was in hospital for a month and rejoined my unit south of the Po to prepare for the last major battle in Italy.

'When we heard the war had ended we fired'

Image: Queen Elizabeth II greets Ganju Lama, an Indian winner of the Victoria Cross, in DelhiOn the very first night two officers were killed and all the three company commanders were wounded and had to be evacuated. So the battle second-in-command, a Major Andy Hardy, was told to rush forward.

Again the Indian 8th Division was given the task of crossing the Senio. This is April 1945. We secured the bridgehead and advanced through the city of Carrara, famous for its marble, and eventually reached the Po.

We were preparing to cross the Po, which was the last major river obstacle when the war in Europe ended. When we heard that, every officer and soldier took his weapon out and fired.

37 Victoria Cross winners in the Indian Army

It was at that battle of Senio that my battalion earned its first Victoria Cross. Namdeo Jadhav, who was a company runner with great bravado, had destroyed German posts and evacuated the wounded for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross (the highest British award for bravery in battle). There were 37 Victoria Cross winners in the Indian Army of 2 million men in World War II.

Having crossed the Po we went to Ochio Bello, which means nice eyes. There, the three Maratha battalions together had a Satyanarayan puja, a hockey match in the village square and treated the local Italians to a desi khana.

We were ordered to return to Taranato to be shipped back to India to prepare to fight the Japanese. Five hundred miles short of Bombay, we heard that atomic bombs had been dropped on Japan.

Taking the homeless Count home

One of the reasons we got on very well with the Italians was that our men picked up the local language very fast. After we captured Florence, we had an Italian military liaison officer who knew another Italian family that had been ousted from their mansion by the Germans. The British had prohibited the Italians from going back. The liaison officer mentioned this to the commanding officer.

At the dining table the CO asked for volunteers. I put my hand up. 'If you get caught,' the CO said, 'we won't help you.' I was a youngster. I got a truck and told that Italian family of five -- the man was a Count -- to get in and packed the back of the truck with rations.

Sure enough we were stopped by the British military police. They asked me what I was carrying. I said 'rations.' They took a look and waved me off. I took the family to their home. Their surviving daughter still keeps in touch with me. I used to go their home on my days off and also visited their chapel.

Fifteen years later when I went back, a woman came and told me she was six when my unit passed through. She remembered me coming to the chapel. The Count was a writer and had one of the finest wineries called Chianti Classico.

'Your Holiness -- I am from India'

During that time Pope Pius XII had a general audience for the troops. I was standing in the passage. He passed me by and stopped. I was wondering what sin I had committed. He asked me, 'Son, where are you from? Are you from Canada?' I said, 'No, your Holiness.' 'Are you from South Africa?' I said, 'No, your Holiness -- I am from India.' He immediately blessed me, put his hands into his voluminous robes, took out a rosary and said, 'This is for your mother.'

'The British never gave us credit'

Image: A Filipino worker cleans General MacArthur's statueIn Bombay we were told to go to Belgaum for jungle training in September 1945. This brigade -- the 268 Indian Infantry Brigade was under the famous General K S Thimayya. He was the brigade commander and our unit was selected to go Japan.

We went to Japan as the Army of Occupation months after the atomic bombs were dropped. We were there from 1946 to 1947. I visited Hiroshima on March 6, 1946 -- five months after the bomb was dropped on the city. By then I was one of the first Indians to get a regular commission in the British Indian Army.

We had to disarm the Japanese, confiscate weapons and subversive literature. We were based in the fishing village in Hamada, 100 miles south of Hiroshima.

The Japanese were so happy with us that when we left Hamada in September 1947, the mayor presented us a 500-year-old samurai sword, which still hangs in the Maratha Light Infantry first battalion's mess at Kota.

General Douglas MacArthur (the supreme commander of the Allied forces in Japan) was very aloof. He wasn't a friendly sort of general. We only saw him one when we did a Guard of Honour for him.

When India got Independence, I had the privilege to hoist the Indian tricolour in Japan about five hours ahead of Indian Standard Time on August 15, 1947. I was the adjutant of the battalion and had the privilege to be the first Indian to officially hoist India's flag.

The courage of the Indian soldier

Our men were never overpowered by the presence of white skin. Each division had three brigades, each brigade had three infantry battalions -- two Indian and one British. This again was a way by which the British battalion kept an eye on the desis.

In the orders and awards, the British battalions were absolutely raddi (rubbish).

The British correspondent of the Illustrated London News wrote an article on the Italian campaign saying there was little doubt that the Indian 8th Division was by far the best division in the 8th Army.

It is wrong to say we were pushed in as cannon fodder, we were not. The South African armoured division, which fought alongside us, had the highest respect for us -- the same for the Americans, the Brazilians, the Free French and the Canadians. Our battalion presented a Maratha sword to the Canadian tank regiment -- the 14th Calgary regiment -- that supported us.

The British never gave us credit

The only people who tended to be rough were the British, and to some extent the Australians. But we had no dealings with the Australians in Italy, in the Western desert yes. Four Victoria Crosses were won by the 8th Indian Division; all four sepoys -- Kamal Ram, Lama Gurung, Namdeo Jadhav and Haider Ali. The fifth Victoria Cross was won by the 10th Indian Division's Naik Yashwant Ghadge of the 3rd Maratha.

But the British never gave us credit. Our unit went abroad in 1940 and only returned in 1945.

On our way back, the ship's adjutant, a third rate British officer, found our men sleeping on the deck and kicked them.

I was the adjutant of the battalion and told him, 'Don't you do that! These men have been fighting!'

'For 15 years I have been writing about the need for a truly national war memorial'

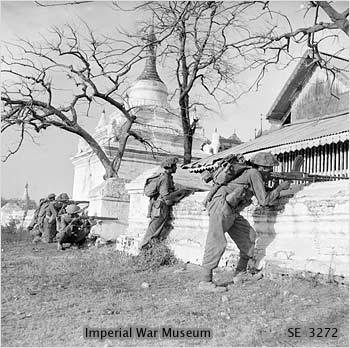

Image: Indian troops among the pagodas of Mandalay, Myanmar.Photographs: UK government public domain

In London, outside Buckingham Palace, they put up a memorial to all the whites -- Australians, Canadians, New Zealanders, South Africans. It was after 50 years that Baroness Sheela Flather, a Punjabi, was horrified to know that there was no memorial to Indian soldiers.

She fought and got a prime spot given on the road from Hyde Park corner to Buckingham palace. She raised 5 million pounds and put up a memorial. On the insides of which are the 37 names of the Victoria Cross winners; at the foot of it two gravestones to mark those who died in World War I and World War II.

We are no better. For 15 years I have been writing about the need for a truly national war memorial in the media. When General (K V) Krishna Rao was the army chief, he had a lovely plan ready, but the bureaucrats do not want the armed forces to come into prominence.

In 2006 the Italian government had a memorial ceremony in Cassino and representatives from all the Indian army units that took part were sent there. In 2007, I received a gold medal from the Polish army.

Of the four young officers who sailed to Italy to fight in World War II, only two are left. Captain Mohite, who left the army in 1947 and lives in Pune, and me.

article