| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Indian religion is such an untouchable subject'

He shares his home with two goats, a few stray dogs, roosters (whose sharp trill punctuates his dialogue), cockatoos, various other exotic birds and on a visit in October a few orange-robed Bauls, Bengali minstrels, were staying too.

An Indian-style tent was anchored in the backyard. His tow-haired troupe of young sons rocketed about the home (he also has a 14-year-old daughter).

Cups of Chai, soft drinks and Indian hospitality flowed as his wife and illustrator Olivia Fraser moved around the home making sure all was well. "Boys, do you need anything?" she asked of the pair of smiling Bauls, who were disappearing into the kitchen to cook either for themselves or for all.

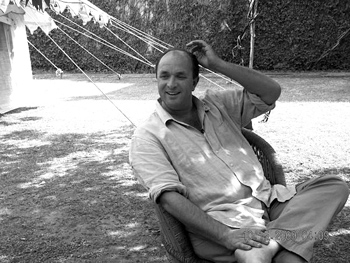

Dalrymple, comfortable in a sky-blue Indian cotton shirt and khaki trousers, lounged in the cane furniture parked in the shade on the velvet green lawn, colourfully recounting to visitors how his home is nearly equidistant from the Google and Microsoft Asia headquarters in Gurgaon as well as villages belonging to the nomadic Gujjar people.

Dalrymple's total ease with his surroundings, his amiable, no-formalities, chalta hai manner, the steady excitement in his voice as he talks (he laughs a lot) and the excessive nervous energy he waves his hands, shakes his leg and hardly keeps still -- reminds you much less of a Cambridge-educated Scotsman (and the son of a British peer, a baronet) and much more of a Punjabi or a typical North Indian.

The writer's innings with India are long and colorful -- affectionate -- and he is as Dilli as Chandni Chowk Chaat. His first trip to Delhi was when he was 18. He wrote his first book on India at 29 -- City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi -- in 1993 and has followed up at regular intervals with four more insightful books, writings for international magazines and documentaries on the country ever since, that present India, in all its engaging hues, to the West.

His last two books were on Mughal India in decline -- White Mughals and The Last Mughal -- and are volumes in a four-part series that required passionate research. But Dalrymple took a break from chronicling medieval India: "I thought I needed to get out a bit. I have been 10 years in the archives and I was about to turn into a dusty manuscript!" -- in 2009 and is back with his latest book Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India.

He still enjoys doing the firangi-bounding-around-India routine "I have been running around the country for 25 years. There is nothing new about that. But this was a new area to delve for me. I have just had the most lovely year doing it -- the most gorgeous year."

Putting together Nine Lives was a perfect excuse to circumambulate India a few more times in a whirlwind manner, getting to know his adopted land a bit deeper on each occasion.

"I got to spend a month in Kerala, I was two weeks in Goa before I abandoned that story. I saw beautiful bits of rural West Bengal I had never seen before. It's a dream really. What a privilege!"

The seed for the idea of Nine Lives -- "This is my first Hindu book. It is an overwhelmingly Hindu book" -- came to Dalrymple more than 20 years ago when he began to gingerly sample the multiple, layered flavours of Hinduism after coming to India. He remembers initially being overwhelmed while trying to make sense of the essence of Hinduism.

As he delved deeper into Hinduism, slowly piecing together finer understanding about individual strands of the religion and philosophy, he knew he had a great book to craft.

Nine Lives recounts the tales of nine Indians, in their own voice, whose faith led them to carve out unusual lives.

Hari Das is a labourer and part-time jail employee from Kerala who seasonally becomes a theyyam dancer and nightly the Lord's avatar. Mohan Bhopa is a traveling Rajasthani teller of epics whose singing and dancing performances offer tales of the folk deity Pabuji. Srikanda Stpathy, who lives in Swamimalai, Tamil Nadu, near Tanjore, is a member of the premier idol-making Brahmin family of India. Tashi Passang is a Buddhist monk who escaped from Tibet with the Dalai Lama.

Lal Peri is a Bihari Muslim who fled Sonepur, in the face of religious persecution for Bangladesh and fled Bangladesh, in the face of immigrant persecution, for Pakistan and became a sufi. Rani Bai, a Devdasi and a devotee of Yellamma, is from Belgaum. Prasannamati Mataji is a wandering Jain nun ("The Jain story is the one that most surprises firangs," says the author). Debdas and Kanai are Bauls who belong to a sect of wandering Bengali minstrels. Manisha Ma Bhairavi practises tantric rituals at a cremation ground in rural Bengal.

William Dalrymple spoke to rediff.com's Vaihayasi Pande Daniel:

Why did Nine Lives have such a long gestation? You had the inspiration to write the book 12 years ago.

The book began to cohere because I had an idea about writing a book about Indian religion since 1997 had a commission from my publishers following a series I did on TV called Indian Journeys (This BBC series looked at the journey of three Indians one Hindu, one Muslim and one Christian. The Hindu journeys to the source of the Ganga, at Gaumukh in the Himalayas. The Muslim, a sufi, makes a voyage to Ajmer's Sharif Dargah, while the Christian travels from Cranganore or Kodungallur in Kerala to Mylapore in Tamil Nadu.)

I found it very difficult to make a book work because it is one of the most perilous subject to write about in the sense that Westerners have been misinterpreting Indian religion for so long and the number of traps you can fall into -- whether it is sounding like an Orientalist or like a naive hippy going around ashrams or someone like Madam Blavatsky chasing ectoplasm with the Theosophists through the streets of Madras or Allen Ginsberg getting the vibes on the ghats of Benares.

All these are potential traps and certainly any Westerner in this country writing about religion is guilty of all charges exoticism, Orientalism or whatever.

People here are apt to assume that you are some searcher after the exotic.

One of the reasons I have not done (a book on religion) till now is that it is such an untouchable subject. People here are apt to assume that you are some searcher after the exotic and I hope I have found a way around that because 80 percent of this book is reported speech. The narrator is almost absent.

I hope I have imposed myself on the material very little and I have not reflected my prejudices, desires or, frustrations or Western spirituality onto the material and I have let the material speak for itself, I hope in a non-judgmental fashion.

Let people say what they have to say and present it and the readers decide for themselves if they want to condemn the Jain nun or not.

'These people are far from being weird freaks on the edge of Indian society'

Religion is as a good a way into the human heart. Just as novelists use love and sex as a way of defining their characters often, so it seems to me, a person's religion and what they do for their religion and their devotional tendencies are as revealing as anything else in the human character.

A country's religion is as good a path into a country and a people, a nation, a society, as any other route you can choose as a writer.

And one of the lovely surprises of this book is that having set out to write a book about Indian religion I have written, in the end, a book about nine different gateways into nine different Indias and each these universes are amazingly self contained.

The Jain world is entirely self referential. The Devdasis is a world to itself. Each has its own moral compass, its only moral universe. Each has its own moral system, value system.

Should you say that a Jain nun starving herself to death is a wicked waste of a life? Or is it an act of extreme heroism?

India has hundreds of religions and religious sects. How did you choose? And there are groups not represented at all.

Ultimately, the choice was done on simply which people I found most interesting.

On the short list there must have been 20 people who I interviewed in as much detail as the nine who did finally make it in.

You judge each story on its own merit and I put in the nine which I thought were the most interesting.

Sikhs are missing. I never got a handle into the Sikh (community). I thought I would maybe do an Akali. But there are lots of Sikhs in the City of Djinns! I interviewed Jews. And a Syrian Christian oracle. But that got dumped because it was too similar to the Haridas story. The theyyam dancer was so good. Lovely material.

I (tried to include) a Mujahideen commander from Kashmir who was a jihadi, went and trained in camps in Kandahar and came back and ran his Mujahideen (group) and became disgusted by what he saw and became a Sufi by the Dal lake.

The other lovely thing was finding the way that the figures range from the very ordinary like Stpathy who is a member of his local Lions club. He is a very unexceptional character, a local businessman and a very ordinary middleclass man in all sorts of ways except for the fact that he is the 35th generation of this great tradition.

And the characters range from that to hardcore Naga sadhus living in Tarapith (Bengal).

One of the pleasures of (doing) this book was finding the humanity of people on the margins and (attempting) to humanise the exotic. And here it does not get more exotic than a skull drinking (they drink blood using skulls as cups) Naga sadhu living in a cremation ground. It is very extreme.

Yet, once you learn their stories you find they are much more integrated into the more familiar India. The Naga sadhu's son is an accountant with the Tatas in Kolkata. And one of the skull drinkers I talked to, his sons were ophthalmologists in the US and he thinks he might go off and join them!

While some of the figures are undeniably exotic and conform in a sense to Orientalist stereotype, I think what I have hoped to do is give them humanity and give them context and find that these people far from being weird freaks on the edge of Indian society are, in fact, far more closely integrated.

'There is so much love in that place'

I hope this book does not show that there are two Indias, but that it shows a whole variety of Indias, all seamlessly connected.

I don't believe there is a distinction between urban India and the 'real India' or village India.

I think what is enjoyable is seeing how much these things connect. Just these two here (he points to the Bauls, Kanai and Debdas, now sharing the lawn with us). Deboo is a pandit's son. He comes from a very middle class background. His father is a big landowner in the village. His brother the police chief.

Kanai is village India, migrant labour, day labourer for a zamindar, father died (because of asthma).

So even in that couple sitting there under the shade there are two Indias. There are innumerable Indias and I explore (just) nine.

Many of the nine lives represented in your book seem to have very sad lives.

Yes Rani Bai's (from the chapter on Devdasis) is a properly sad story. But the Baul story is one of the happiest.

I was surprised by -- I suppose -- how many of these people had embraced their particular forms of the religious life in the face of extreme personal tragedy, whether it was marital break-ups, countries being invaded in case of the Buddhist monk or Lal Peri, the triple refugee (possibly the fourth time if the Taliban have their way).

And what is interesting is that in the West -- particularly, the entire population of Tarapith would have been put in a home, in padded cells, given Prozac and medication. In India they are revered. There is so much love in that place (Tarapith).

And by getting under the skin of someone like Kanai and what he has lived is like George Orwell and The Road to Wigan Pier (Orwell's book looked at England's working class by the author actually living with them). You get invited to an underclass that you look at and see that you were not really aware of.

In the (same) way that Orwell was able to express the lives of the underclass he sees in The Road to Wigan Pier, I have attempted to show that is several of the stories.

'You have the Ram-ification of Hinduism'

I think Indian society is changing very fast. I have no doubts about that. There is the speed of urban growth. The speed of migration from the margins. The way spirituality is changing in both Hinduism and Islam. You get a move from the local to the national.

In Islam you get a Wahabbi textual Koranic Islam coming up with the middle class, replacing a more superstitious local Islam based on the popular folk cult of saints like Sufi saints.

Which is not to say that the middle class don't go to shrines too, but overwhelmingly the new Islam is the textual middle class urban Islam based on literacy and the Koran and partly sponsored by Saudi madrasas.

The Saudis have changed Islam beyond all recognition in this country.

Similarly things are going on, more subtlely, in Hinduism where you have the Ram-ification of Hinduism where mainstream national Vaishnavite cults to Ram and Krishna are taking over from village goddesses... Particularly blood sacrifices are dying out.

Even my tantric skull feeders -- who when interviewed by this academic 20 years ago were merrily slaughtering goats -- now told me that Kali was a vegetarian!

There is a Sanskritisation of these sort of Tantric cults. The Ram-ification is not necessarily the same thing as RSS-isation or BJP-isation. I disagree that the average Hindu is not changing that much. I don't mean Ram-ification in a political sense but in a devotional sense.

For instance, in small Bengali villages where, for example, you had overwhelmingly the cults of the devi, often in the form of the local village goddess you have increasingly temples to Ram.

People have done their Phds on the fact that there (is gravitation towards a) centralising tendency to familiar national gods at the expense of village gods.

The other thing I notice is the regional variants on mythology. The Pabuji epic is a regional variant of the Ramayan. In the Pabuji epic it is Pabuji who goes to Lanka to steals camels from Ravan. Obviously, there is no mention of this in the mainstream Ramayan.

Villages now see the mainstream Ramayan on their televisions in Rajasthan and wonder: 'Where's Pabuji? Why isn't Pabuji here?'

The Pabuji epic is among the Rabaris, camel herders. There is no camel herding anymore. And the epics, which were sacred to the camel herding castes, are also about cattle and cattle herding. And both these things are in decline.

The Rabaris are drifting off to the cities and engaged in road building and at building sites. They no longer have the connection with camel herding that made the myths relevant.

Where do you think the characters in your book -- or rather the people they represent -- will be 20 years from now?

Already, the most fragile, unquestionably, in the book is the bardic tradition of Pabuji -- threatened by literacy itself.

One of the amazing things that emerged in that story is that oral tradition flourishes in minds which are illiterate. The literate do not have the capacity to remember what the illiterate do.

What Komal Kothari (the well-known Indian anthropologist and folklorist) found (while studying Rajasthani folklore of the Langas or Rajasthani bards) that (he decided) 'instead of taking all the stuff down why don't I send (one of the) Langas to adult literacy class and let him write it all down.'

And one of the things he (Kothari) noticed was that (after the literacy classes) when the Langa performed he would check his notes. The very same man who had known the stuff (thousands of songs) by heart began to forget them as he became literate.

So that (the bardic tradition) I would say is the more fragile tradition.

The Devdasis are not in good shape because of AIDS. Many of them have died. AIDS in India spikes in certain high risk categories, some of which are the same sex partners among men; another which is the Devdasi.

Stpathy's craft, I think, will survive in some form because there is a demand for these things. It will survive as a business, but not as a family tradition.

The Buddhist monks are here to stay. These guys (Bauls) are flourishing.

If you got to Kenduli (the premier festival of the Bauls, Bengali minstrels, held in the town of Kenduli near Santi Niketan on Makar Sankranti in January each year) there are more madman each year. Though what's interesting is that in the old days apparently the fakirs and the Bauls used to travel together. Now there is a diverging of paths and they don't mix much. So there are changes going on there.

Whether the Sufis will survive in 20 years, who knows? I don't know. That is a crucial question.

'I love India's plural nature'

I have lived here for 25 years. Like immigrants all over the world, I am both this side and that side. I will never become completely Indian.

I am very flattered that people think I am Indian enough for me to get the Crossword Prize, which is exclusively for Indians. The most pleasurable book prize -- a book prize I am most proud to have won as much for being included as for winning it.

But India is home. I live here ten months of the year and the kids are at school here (in the British School). I am in exactly the same situation as the many Indians who have lived 25 years in Britain. Are they British? Yes and no. They are insiders and they are also outsiders.

You can't, in one life, totally cross over. Mark Tully was born here and lived all his life here. Is he Indian? Up to a point.

So is India a giant, life-long reporting assignment?

It seems to be unless I go off to the Maldives. I have written one book on the Middle East (In Xanadu) and many people feel its my best book. My kind of beat runs between Athens and Kolkata.

After all these years in India, are you drawn to aspects of Hinduism?

When I arrived in India I found Hinduism far more foreign than Islam. Islam is an Abrahamic religion along with Judaism and Christianity. We are the children of Abraham.

Islamic art derives in part from Byzantine architecture. So there is much that is very familiar the courtyard, the arch. The early mosques in the Middle East looked like churches.

I felt that Islam was a much more familiar culture -- theologically, textually and artistically. And Hinduism, while I was attracted to it, I did not understand or find easy to comprehend. There were things that I immediately loved like the Mahabharat. I loved Pahadi paintings and Chola bronzes.

One of the pleasure of researching and writing this book is becoming much more familiar (with Hinduism).

What has influenced me unarguably is India's pluralism -- the sheer variety of faiths and cultures here which mean it is very difficult to believe wholly in one orthodoxy. And as (Nobel Laureate) Amartya Sen puts it heterodoxy is the natural state of affairs in India.

Pluralism and heterodoxy are two things that come naturally to India.

The simple understanding that Hinduism is not one religion but many contained within the capital H of Hinduism is a whole world of different devotional practices. Discovering this made me understand.

Coming from an Abrahamic faith where there is one book, and a set text so to speak, you look for that in Hinduism and you look for what they believe and the simple understanding they don't believe any one thing they believe a whole variety of things often which contradict each other.

The Bauls, for instance, don't believe in a transcendent deity, they don't believe in a temple, they don't believe in the idol while the Stpathy lives to make idols.

I am not uncomfortable with that pluralism. It is one of the things I love about this country. I love its plural nature.

You have been here 25 years. What still has the capacity to stun you?

Every day I am still surprised about this country. Every day.

Half an hour before you were here, the MTNL (Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Limited, the fixed-line telephone utility in Mumbai and New Delhi) were here to connect the Internet and the whole question of how far you give baksheesh or not and the knowledge your Net is going to stop working tomorrow if you don't give Rs 500...

(It is an) enjoyable state of muddle.

When you go back to England and Scotland you must be asked how India is faring, if India is stable and where India is headed.

I think the Indian democratic project is a remarkable success. If you look around your neighbours no one has managed to pull off what you guys have pulled off. And seeing the last election I just felt so proud of India for sending the BJP off and seeing such a fabulous result.

That said, as we all know there are huge areas of the country which may not have a level balance. Suddenly, Bombay can erupt.

Since I have been living here we had all that stuff about reservation for Gujjars. This is a Gujjar area. We could not leave the house for a week. We may be half a mile from Microsoft Asia, but we are less than half a mile from the Gujjars too. And little things like we have had to employ a Gujjar chowkidar. If we had a Jat here we would be in trouble.