| « Back to article | Print this article |

Will Sonia Gandhi break Indira's record?

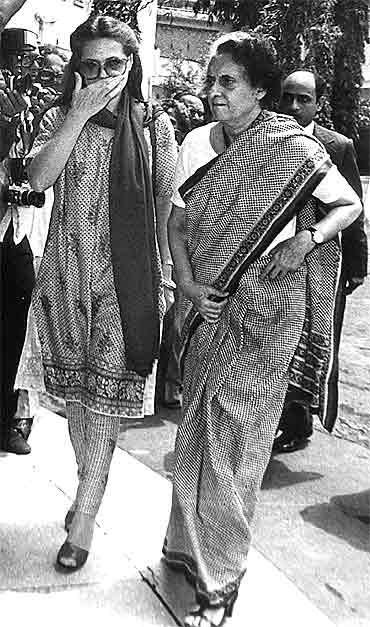

As Congress President Sonia Gandhi turns 64 today, journalist Rasheed Kidwai, who wrote Sonia: A Biography, examines her legacy. How does she compare with the original Mrs G?

Since it was published in December 2003, before Sonia Gandhi led the Congress to an unexpected positive outcome at the elections a few months later, journalist Rasheed Kidwai's book Sonia: A Biography has been going from strength to strength. Apart from being translated into Hindi, Telugu, Marathi, Punjabi and Urdu, an English edition was also published in Pakistan in 2005.

Next month, the book is expected to come out in a paperback edition, and in a prologue written specially for it, Kidwai offers some fresh insight into Sonia Gandhi's reign as the head of the Congress party, her equation with Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh, her aversion to corruption which remains the Congress party's Achilles' heel, and the heir apparent, Rahul Gandhi.

The original Mrs Gandhi -- Indira -- had delivered a second successive election victory for the Congress in 1971 but before that she had to win a war. The reigning Mrs Gandhi -- Sonia -- has also led the Congress to consecutive poll successes (in 2004 and 2009) but she hasn't had to go so far as to fight an external war, though there have been many domestic battles, writes Kidwai, whose second book on Sonia Gandhi, 24 Akbar Road, is soon to be released by Hachette Books

'Sonia has done many things differently from her larger-than-life predecessor. But, since numbers are what decide polls, the winner of Mrs G vs Mrs G can be called with certainty only in 2014 if Sonia can deliver a 3-2 score by winning three consecutive elections.'

While remaining an ardent admirer of her mother-in-law, Sonia has also done things very differently, points out Kidwai in his prologue.

'Since 1998, when she was a reluctant entrant into politics, Sonia has been anything but a control freak, a term often used for the Congress high command under her mother-in-law. With the exception of J B Patnaik in Orissa and Vilasrao Deshmukh-Ashok Chavan in Maharashtra, Congress chief ministers have seldom been shunted out by Sonia.

'Even her core team, consisting of Ahmed Patel, Oscar Fernandes, Janardhan Dwivedi, Digvijay Singh and others, has remained intact with minor fluctuations. Unlike in Indira's days, the team of advisers has not grown into a cabal at whose feet the party and the nation have to worship.'

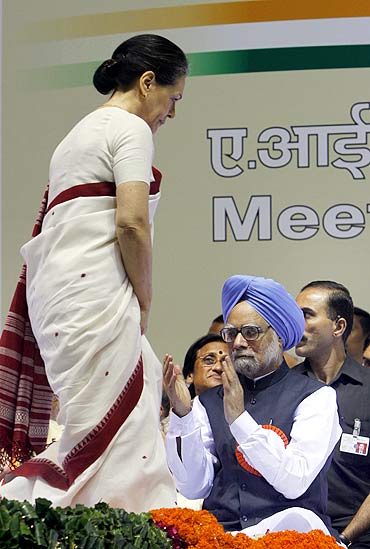

When power was waiting at the door of 10 Janpath, she made Manmohan Singh the prime minister, a step which might not have been expected of Indira who in her time did not allow what she considered parallel centres of power to develop, writes Kidwai.

Click on NEXT to read further...

Allowing dual power centres

Sonia's own long-term political strategy hinges upon Dr Singh's clean image and good governance plank, says Kidwani. By 2014, the Congress, perhaps under a younger leadership, would need to display Dr Singh's tenure as exemplary. On the other hand, a tainted United Progressive Alliance-II may force the party to sit out as it happened during 1996-2003 when the P V Narasimha Rao regime's numerous acts of omission and commission had a telling affect on the Congress's fortunes, he says.

The dual power-centre model and coalition dharma also pose their own problems for Sonia. When the UPA was formed in 2004, Sonia had cleverly earmarked a political role for herself as UPA chairperson while the executive role of running the government was assigned to her appointee, Dr Manmohan Singh. But in practice, the Westminster model of parliamentary democracy was designed in a manner of functioning as 'prime ministerial democracy'. The prime minister being 'the shining moon among lesser stars' was expected to act swiftly and often secretly, as demonstrated by Indira Gandhi on numerous occasions.

'In UPA, the decision-making process envisages a huge consultation route calling for meetings between the "big two" and their set of advisors who often work at cross purposes,' writes Kidwai

'Between 2004-10, the UPA functioned well under Manmohan Singh but the coalition faced innumerable challenges from within and outside. In the larger context, it worked more like a bureaucratic machine than a political conglomerate. There were many lacklustre performances in some of the key portfolios, while frequently ministers differed with each other, sidelined their juniors and cared little for a sense of accountability, a basic feature of parliamentary democracy.'

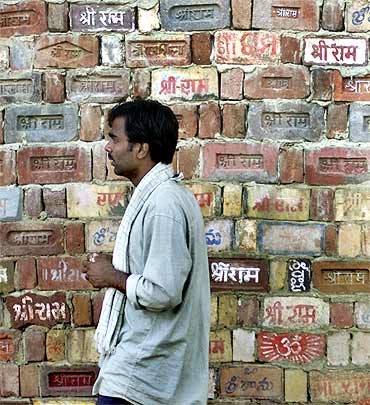

Inaction over Ayodhya

Why has the Congress not played a proactive role following the Lucknow bench of the Allahabad high court's verdict in the Ram Janambhoomi case? Kidwai offers his take: 'The Congress's lack of enthusiasm in acting as peacemaker showed Sonia's own assessment of Ayodhya dispute as the Congress's Achilles heel.'

India's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, was quickly dragged into the Ayodhya imbroglio in December 1949 when idols were surreptitiously placed inside the 16th century Babri mosque. And decades later, in 1986, when Rajiv Gandhi was prime minister and the Congress was in power in Uttar Pradesh, the fast-paced events leading to the opening of the lock surprised even the Bharatiya Janata Party.

After the Babri masjid demolition, Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao became disillusioned and wrote with an air of dejection that while the Kalyan Singh government and the BJP were largely responsible for the "wanton vandalism", his Congress colleagues in the ministry, too, had been guided by "political and vote-earning" considerations. "They had already made up their mind that one person had to be made historically responsible for the tragedy. They got a stick to beat me with. I understood it."

With such a history, Sonia-Manmohan's hesitation in acting as an Ayodhya arbitrator was not without reason, argues Kidwai.

Zero tolerance for corruption

This is not the first time that the Congress has been faced with corruption charges, but Sonia Gandhi's reaction to the charges have been different, writes Kidwai.

Politician Sonia Gandhi is said to be acutely conscious that more than evidence and facts, public perception matters on sensitive matters like corruption in high places. So far, her assessment is that the integrity of the prime minister and the Congress leadership is somewhat intact but she seems to be mindful that public perception is changing and another scandal involving a Congress leader may drastically alter the entire game, says Kidwai, who adds: 'It was not enormity of defeat in Bihar but spotlight on corruption that bothered Sonia Gandhi most.'

For Congress insiders, Sonia's anxiety was a reflection of her family's difficulties in tiding over ghost of Bofors and a series of scandals that badly damaged the credibility of her husband Rajiv Gandhi's government, he says. In some ways, Bofors singularly contributed to Rajiv's downfall as it gave an otherwise demoralised and fragmented opposition a sense that together they could humble the Congress which was holding 413 MPs in a 542-member Lok Sabha.

How Sonia Gandhi came into the 2G spectrum scam involving former telecommunications minister A Raja is interesting. When the enormity of Raja's alleged misdeeds became evident, the UPA for over six months virtually did nothing, says Kidwai. Behind the scenes, an anxious prime minister and his men reportedly tried to gauge Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam chief M Karunanidhi's mood. Sonia was brought into the picture when intelligence agencies convinced the prime minister that a major scandal was about to break.

The political leadership then reportedly engaged a former chief minister of Punjab to sound out a governor considered close to the DMK, Kidwai writes. By the time a reluctant Karunanidhi was made to see reason, the opposition had decided to stall Parliament to demand a Joint Parliamentary Committee probe.

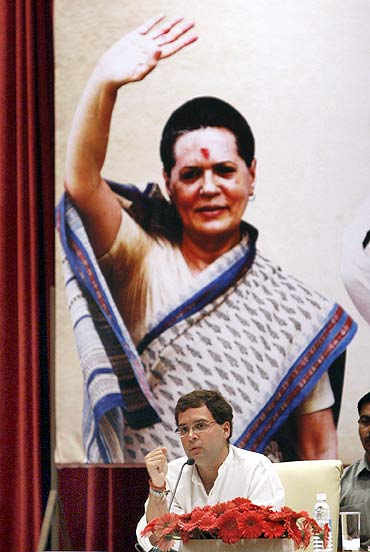

Grooming the heir

Kidwai points out that unlike the crude grooming of her sons Sanjay first and Rajiv later by Indira Gandhi, Sonia's grooming of Rahul is being done in a contrasting manner.

'In the Congress organisation, Rahul's presence posed piquant problems for a number of party leaders who had cut their political teeth under Sanjay and Rajiv Gandhi. They lacked rapport with the younger AICC general secretary. Even the old guard like Pranab Mukherjee went public saying he did not see himself serving under a government that might be headed by Rahul Gandhi.'

Rahul's near-obsession with inner-party democracy particularly among the young wings of the party failed to show results. Rahul engaged the Foundation for Advanced Management of Elections, an NGO run by former election commissioner J M Lyngdoh and K J Rao that specialised in conducting "free and fair" polls.

'Amid stiff opposition from the Congress, Rahul assigned FAME the task of streamlining organisational polls in the Indian Youth Congress and the National Students Union of India. Rahul also gave an undertaking to image-conscious Lyngdoh and Rao that that no person having a criminal record will be allowed to contest party elections. More significantly, Rahul agreed that all disputes relating to organisational polls would be settled by FAME and not by the party. This was a drastic measure considering the bigwigs always fancied having influence over the NSUI and Youth Congress,' writes Kidwai.

'FAME began well by conducting Youth Congress and NSUI polls in Punjab, Delhi, Uttarakhand and other states in a rather transparent manner but senior Congress leaders and regional party satraps were far from pleased. Party leaders who did not want to come out in open against FAME lamented the former bureaucrats' tendency to target close relatives of established party leaders. Moreover, the allegation was these election officials focussed on "free and fair" polls, ignoring other critical elements in politics such as caste considerations, winnability in polls and factional balance among regional satraps.'

In spite of these teething problems and the rout in Bihar assembly polls where the Congress nominees forfeited deposits in over 200 out of the 243 seats, Rahul continues to be viewed as a prime ministerial candidate, says Kidwai.

So what is Rahul Gandhi really like? Kidwai offers a glimpse: 'At his 12 Tuqlaq Road residence, Rahul mostly wore kurta pyjama during his meetings with Congress workers but in the evenings he was often seen in jeans and T-shirt.

'Visitors at his residence are greeted with a notice board stating two rules: 'No autograph', and 'Do not touch feet'.'