| « Back to article | Print this article |

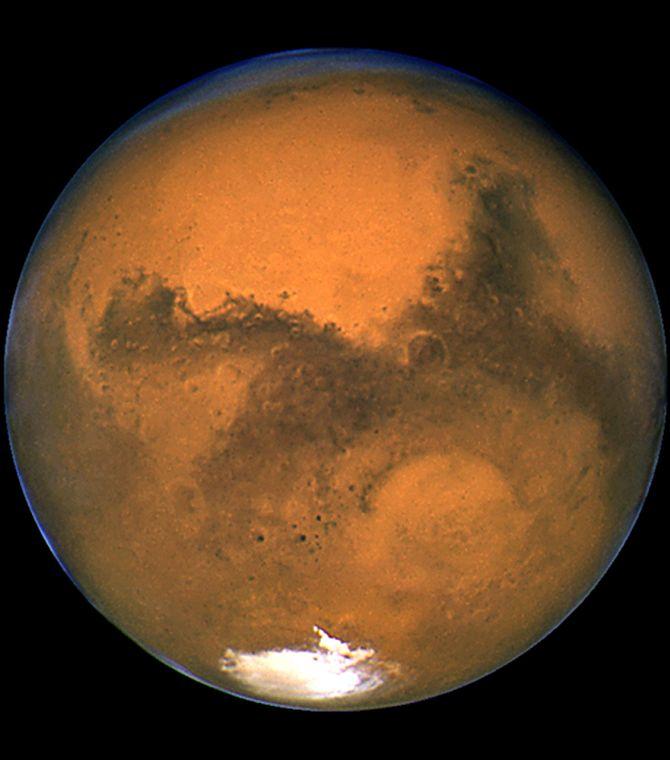

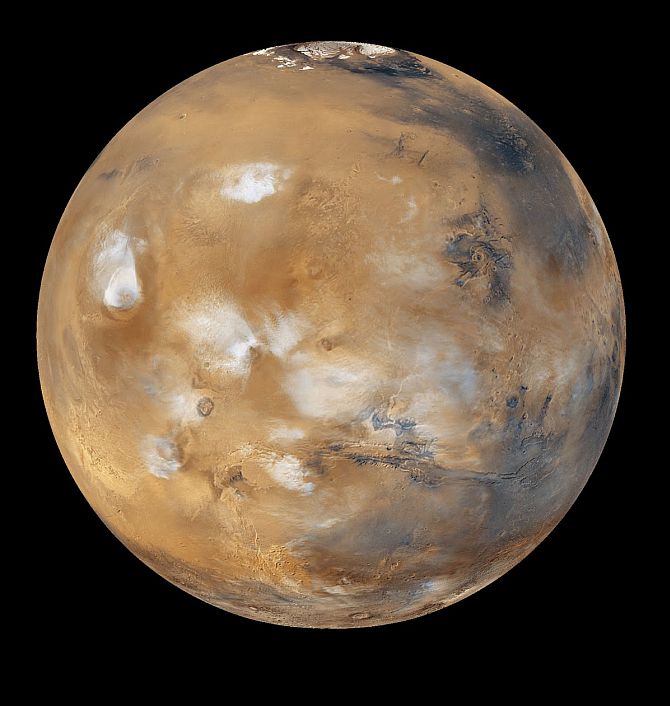

Why India needs to send a mission to MARS

Critics of the Mars mission are asking why India should spend Rs 450 crore on this esoteric mission when there are so many other national priorities. The argument is too simplistic. Moreover, the technological experience of this mission is going to help us in more earthly applications, says Dinesh C Sharma.

If everything goes as planned, an Indian spacecraft will be on its way to planet Mars early next month.

The mission has generated great interest in India and elsewhere given the success the Indian space agency has had with its lunar mission, Chandrayaan-1. However, there is confusion in the minds of people about the goal of this mission.

Is it about national pride, as widely projected? Or about proving a point to China which is surging ahead of India in the Asian space race? Or is it just an exercise to boost sagging morale and image of the Indian Space Research Organisation which faced the flak for the infamous Antrix-Devas deal?

The Mars Orbiter Mission -- India’s ever mission to another planet -- is more of a technology mission than scientific or strategic one.

India wants to demonstrate that it has developed necessary technology and know how to design, launch and manage an inter-planetary space mission.

Comparisons with the mission to the moon, Chandrayaan, are natural, but the fact is that the Mars mission is far more complex technologically yet less ambitious in its science goals.

Click on NEXT to read further...

Why India needs to send a mission to MARS

Similarities between the two missions end with the fact that both are orbiters and use similar launch vehicles. The upgraded version of the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle-XL will be used for the launch next month. PSLV has emerged as ISRO’s workhorse with a history of successful launches in the past two decades.

The major test for MOM, therefore, begins after the launch. Sending a man-made object to orbit around the red planet, which is located some 400 million kilometers away from the earth, is fraught with unknown dangers and is a major technological challenge.

It means propulsion systems and the capability of the satellite to withstand pressures of outer space for long periods are totally different from all earlier missions.

Chandrayaan too was challenging but it had to cover a distance of only 4 lakh kilometers in order to reach an orbit around the moon.

The journey time for MOM is estimated to be about 300 days, compared to 5.5 days it took Chandrayaan to reach the lunar orbit. For the satellite to cruise through such a long journey, it has to be rugged and be able to withstand cosmic radiation.

Several American and Soviet missions to the red planet launched in 1960s could never complete their journeys. Secondly, the trajectory to reach Mars is complicated.

After its launch from the Satish Dhawan spaceport at Sriharikota next week, the spacecraft will circle in an orbit around the earth six times before escaping from the earth’s gravitational force and entering into a Martian Transfer Trajectory. After this, it will enter an elliptical orbit of 372 km by 80,000 km around Mars.

Click on NEXT to read further...

Why India needs to send a mission to MARS

The spacecraft will be manoeuvred through onboard propulsion system which will be triggered at designated intervals to propel MOM into desired orbit. Signals will be sent from the Indian Deep Space Network at Byalalu, 40 km from Bangalore, to fire onboard motors at precisely calculated points to accelerate the velocity of the spacecraft.

Planning and execution of crucial manoeuvres is as important and critical as the launch itself. While it took just 1.3 seconds for a signal to be sent to Chandrayaan, it will take 20 minutes to reach MOM.

The technology part of MOM is more challenging than the lunar orbiter, but its science part appears to be far more modest. The Mars orbiter will carry compact science experiments -- five payloads totalling a mass of 15 kg.

These include the Mars colour camera, methane sensor for Mars and thermal imaging infrared spectrometer. The payloads are designed to collect data for atmospheric, particle environment and surface imaging studies.

Chandrayaan had as many as 11 payloads -- totalling 100 kg -- including those from American, European and other space agencies. It also had moon impact probe which was dropped on the lunar surface. The scientific goals of the Mars mission are, thus, much less ambitious.

Click on NEXT to read further...

Why India needs to send a mission to MARS

The methane sensor is billed as a key scientific payload as it is designed to collect data about possible presence of methane on the Martian surface, which in turn, is supposed to be an indicator of the presence of life forms on the red planet.

Like the finding of water signature by Chandrayaan, Indian scientists are hoping that MOM will give clues about life on Mars. But these hopes have been dashed recently by NASA scientists who have reported that Curiosity Rover, which collected data over period spanning Martian spring to late summer, could not detect any methane.

Still hopes are not lost. Who knows, there could be surprises from MOM.

The Mars mission has also triggered debate on the Asian space race and comparison of India’s space programme with that of China.

Massive funds are being pumped into China’s highly ambitious space venture which includes setting up of a space station on the lines of the International Space Station currently managed by the US and Russia.

China has already sent humans to space and plans more manned missions in near future.

The goal of the Chinese space programme is to establish its supremacy in outer space. On the other hand, India’s space programme is more tuned to national needs and scientific exploration.

Click on NEXT to read further...

Why India needs to send a mission to MARS

ISRO wants to establish itself as a robust space agency capable of designing, building and launching a range of communication and remote sensing satellites, and launch vehicles. It is yet to prove its capability in the field of heavier launch vehicles.

The effort to demonstrate indigenously developed Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle with cryogenic engine has not yet been successful. ISRO is keenly interested in scientific experiments too. Lunar and Martian orbiters are in line with this goal.

The agency is working on satellites for astronomical observations (Astrosat) and to study the sun’s corona (Aditya) as well as second mission to the moon (Chandrayaan-2). This is unlike the Chinese programme which is riding on national pride and superpower dreams.

Critics of the Mars mission are asking why India should spend Rs 450 crore on this esoteric mission when there are so many other national priorities. The argument is too simplistic. What ISRO is spending on this critical mission is much less than a day’s oil subsidy. Moreover, the technological experience of this mission is going to help us in more earthly applications.

India already has its own communication, broadcasting, remote sensing, navigation, research and rescue, meteorological and educational satellites all devoted for various national programmes.

ISRO is, in fact, one of the most cost-effective science agencies we have. With eyes set on the red planet now, it is on the right path.

Dinesh C Sharma is a science journalist and author based in New Delhi