| « Back to article | Print this article |

Why India must remember Sardar Patel

Leaders of today can pay homage to Sardar Patel by being realists, calling a spade a spade, having sound advisors, playing to our strengths etc, says Sanjeev Nayyar.

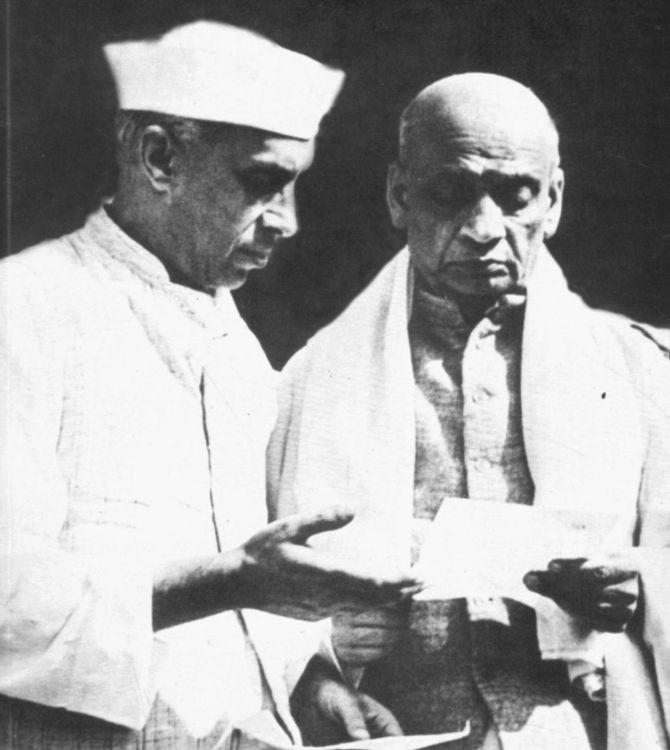

Bharatiya Janata Party leader Narendra Modi's statement that it would have been better if Vallabhbhai Patel had become India’s first prime minister, created a political storm. The Congress claims Patel is theirs, so how could the BJP appropriate his legacy?

Instead of looking at the political side, the article seeks to provoke thought by exploring how some of Nehru’s decisions, that Patel opposed, have impacted the geo-political situation in the Indian subcontinent. This is done through a series of questions, insights and Patel’s views on Jammu and Kashmir and Tibet.

The article draws extensively from the book Patel A Life by Rajmohan Gandhi. I quote from book's preface, 'But the opinion of some that the Mahatma had been less than fair to Vallabhbhai was a factor in my decision to attempt to write the latter’s life. If a wrong had been perpetrated, some reparation from one of the Mahatma’s grandsons would be in order'.

The Congress is on a weak wicket when it says that due credit was given to Patel. Rajmohan Gandhi wrote, 'Falling in 1989, the centenary of Nehru’s birth found expression on a thousand billboards, in TV serials, in festivals etc. Occurring on October 31, 1975 – four months after Emergncy had been declared – the Patel centenary was, by contrast, wholly neglected by official media and by the rest of the official establishment'.

Actually the Congress's attitude was not new.

'That there is today an India to think and talk about,' President Dr Rajendra Prasad wrote in his dairy on May 13, 1959, 'is very largely due to Patel’s statesmanship and firm administration. Yet, we are apt to ignore him'.

Click on NEXT to read further...

Why India must remember Sardar Patel

How did Vallabhbhai become Sardar?

It was during the battle of Bardoli, in April 1928, that someone referred to Patel as the peasant’s Sardar. The appellation caught on. It was due to Patel’s success in fighting the British that the Vallabhbhai of April became Sardar in June and a triumphant general in August.

Is it true that Gandhi nominated Nehru to be independent India’s first prime minister?

Aware that the next the Congress president would be India’s first de facto premier, Azad wanted to continue as president. If Gandhi had his own reasons for wanting Nehru, the party wanted Patel, in whom it saw -- as veteran leader J B Kriplani would later say -- 'a great executive, organiser and leader'.

Even though Gandhi had indicated his preference for Nehru, the party wanted Patel. Twelve of the 15 PCCs had nominated him. Knowing that no Pradesh Congress Committee had proposed Nehru, Gandhi asked Kriplani to propose Nehru’s name during a working committee meeting in Delhi.

As soon as Nehru’s name was proposed, Kriplani withdrew his nomination and handed Patel a fresh piece of paper with the latter’s withdrawal written on it.

Patel showed the sheet to Gandhi, who despite his preference gave Nehru an opportunity to stand down in Patel’s favour.

Gandhi said: 'No PCC has put forward your name. Only the working committee has.' Nehru responded with silence. After obtaining confirmation that Nehru would not take second place, Gandhi asked Patel to sign the statement that Kriplani had prepared. Patel did so immediately.

Of the many reasons for nominating Nehru, Gandhi knew that his selection would not deprive India of Patel’s services though the reverse might not be true.

In the run-up to independence, Patel’s Working Committee colleagues acknowledged his crucial role. On May 11, 1947, Sarojini Naidu called him 'the man of decision and man of action in our councils'.

Said Kriplani, 'When we are faced with thorny problems, and Gandhi’s advice is not available, we consider Sardar Patel as our leader'.

Yet, Nehru became India’s first prime minister.

Click on NEXT to read further...

Why India must remember Sardar Patel

What about Kashmir?

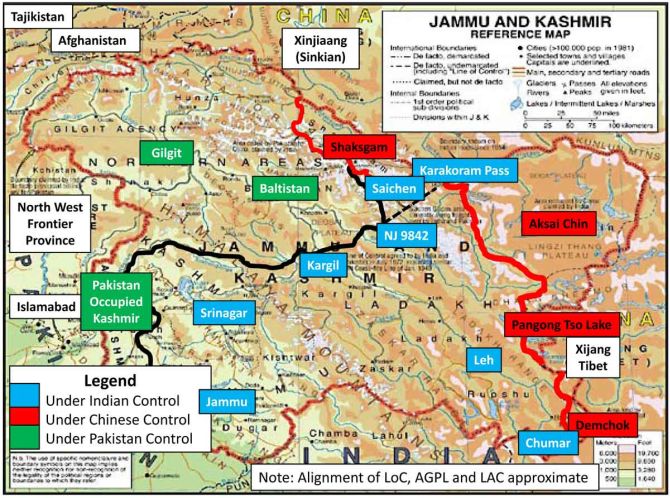

The princely state of Jammu and Kashmir shared a border with Afghanistan and Russia.

'Patel’s lukewarmness about Kashmir had lasted till September 13, 1947. His attitude changed later when he heard that Pakistan had accepted Junagadh’s accession.' Why he changed his mind is beyond the scope of this article.

On October 22, 1947, about 5,000 armed tribesmen from Pakistan entered Kashmir. Patel said the enemy must be driven back. Meanwhile attempts to create a workable framework between Kashmir Maharaja Hari Singh and Sheikh Abdullah failed. Patel supported Hari Singh and Nehru, Abdullah.

On December 2, 1947, Nehru wrote to Hari Singh that Sheikh Abdullah should be the prime minister of Jammu and Kashmir and should be asked to form the government.

With this letter, Nehru took over the shaping of India’s Kashmir policy so far played by Patel as minister of states. Perhaps, Nehru allowed his Kashmiri roots and sentiments to get the better of common sense on this issue.

Nehru decided to refer the Kashmir question to the United Nations. Patel was strongly against such reference and preferred ‘timely action’ on the ground. At the UN, Junagadh and allegation of ‘genocide’ against Muslims were introduced. The question of vacating the aggression in Kashmir was turned into ‘the India-Pakistan dispute’.

If the Pakistanis were driven out of Jammu and Kashmir, and not only the Valley, India would have shared a border with Afghanistan, virtually Russia (Tajikistan today) and have close proximity with the energy rich Central Asian Republics.

Further, occupation of Gilghit-Baltistan has opened multi-dimensional spheres for co-operation/collusion with China now and in the future.

Therefore, Karakoram Highway that connects China with Pakistan was made and an upcoming rail link will eventually link China with the Pakistani port of Gwadar.

Click on NEXT to read further...

Why India must remember Sardar Patel

The moot point is, was it possible to drive the Pakistanis out of princely state of J&K?

Major General Sheru Thapliyal wrote, 'Indian forces therefore had to operate in Jammu and Kashmir under serious handicaps. The enemy could not be beaten by decisively local actions. For decisive victory, it was necessary to bring Pakistan to battle across the international border as was done in 1965. Nehru, the apostle of peace, must have hoped that Pakistan’s aggression in Jammu and Kashmir would be a temporary aberration, that all enemy forces would be peacefully withdrawn from the state under the impartial advice of the UN and that thereafter India and Pakistan would have lived as friendly neighbours.' Read full article HERE (external link).

When the Constituent Assembly considered special status for Kashmir in 1949, Patel followed Nehru’s wishes. The realist that Patel was, he did not trust Sheikh Abdullah. That is perhaps why in private conversation he said ‘Jawahar royega’ (Jawahar will cry). Three years after Patel’s death, Nehru dismissed and arrested Abdullah.

Patel was unhappy with many of Nehru’s steps on Kashmir but never spelt out his own solutions. Seeing the way he handled the merger of Hyderabad (Operation Polo), a ruthless yet carrot-and-stick approach backed up by swift army action could be the way Jammu and Kashmir might have been cleared of the Pakistanis.

Unlike Nehru, Patel was not overtly bothered about international opinion. Perhaps, Sardar thought it was pointless to apply his mind on an issue that was purely Nehru’s baby.

Would terrorism in Jammu and Kashmir have started in 1989 if the entire princely state had become part of India? Anyone’s guess. Note that 43,273 lives were lost, between 1989 and August 19, 2012.

Click on NEXT to read further...

Why India must remember Sardar Patel

And what about Tibet?

Patel wrote to Nehru on June 4, 1949: 'We have to strengthen our position in Sikkim and Tibet. The farther we keep away from the Communist forces the better. I anticipate that as soon as the Communists have established themselves in the rest of China, they will try to destroy Tibet’s autonomous existence. You have to consider carefully your policy towards Tibet in such circumstances and prepare from now for that eventuality.'

While the Chinese were planning the invasion of Tibet, Nehru was aggressively campaigning the cause of Chinese entry into the United Nations.

Excerpts from Patel’s letter to Nehru dated November 7, 1950: 'The Chinese government has tried to delude us by professing peaceful intentions. During this period of correspondence, the Chinese must have been concentrating for an onslaught on Tibet. The tragedy is that the Tibetans put faith in us and we have been unable to get them out of the meshes of Chinese influence. Their actions indicate that even though we regard ourselves as friends of China, the Chinese do not regard us as their friends. The undefined state on the frontier has the elements of potential troubles between China and India. For the first time after centuries, India’s defence has to concentrate on two fronts simultaneously'.

The letter ended with a suggestion that 'we meet early and decide'. The meeting never took place.

How might Patel have dealt with the Chinese invasion of Tibet?

Patel would have strengthened the Indian army garrison in Tibet (it was a contingent of Maratha Light Infantry posted there until 1950), increase the cost of conquest thereby ensuring that the Chinese did not conquer it as easily as they did.

Patel might have tacitly supported the Tibet Liberation Movement, not accepted Chinese sovereignty over Tibet and revitalised the century-old cultural links between India and Tibet.

He realised the importance of retaining Tibet as a buffer between India and China... The minute India lost that buffer, the consequences are there to see.

To be fair to Nehru, it was difficult for him to know how the future would shape out. Having said that, Nehru surrounded himself with glamorous collaborators and ignored warnings of the impending threat.

'Two great Indian leaders warned Nehru and the nation against the impending danger which would come as a result of the liquidation of Tibet’s independence -- one was Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar and the other Veer Savarkar'.

Click on NEXT to read further...

Why India must remember Sardar Patel

Conversely this is what then home secretary V P Menon said about Patel:

'Having selected his men, Patel trusted them entirely to implement his policy. Sardar never assumed that he knew everything and he never adopted a policy without full and frank consultation.'

It is very difficult to undo the past, but in hindsight the Indian subcontinent would have been a different place had Patel become India’s first prime minister.

Leaders of today can pay homage to Sardar Patel by being realists, calling a spade a spade, having sound advisors, playing to our strengths etc. Our policy should be guided by a policy of enlightened self-interest.

High principles must be backed by sound armed strength to see they are brought into practice.

Hope the Statue of Unity constantly reminds us of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel’s virtues.

The author is a national affairs analyst and founder of esamskriti.com