| « Back to article | Print this article |

Why India MUST analyse China's world view

Former Indian foreign secretary Shyam Saran, while delivering the Second Annual K Subrahmanyam Memorial Lecture, speaks on what India needs to know about China's world view. The concluding part of the two-part series.

Read the first part here

In dealing with China, therefore, one must constantly analyse the domestic and geopolitical environment as perceived by China, which is the prism through which its strategic calculus is shaped and implemented.In 2005, India was being courted as an emerging power both by Europe and the United States, thereby expanding its own room for manoeuvre. The Chinese response to this was to project a more positive and amenable posture towards India.

This took the shape of concluding the significant political parameters and guiding principles for seeking a settlement of the border issue; the depiction of Sikkim as part of India territory in Chinese maps and the declaration of a bilateral strategic and cooperative partnership with India.

In private parleys with Indian leaders, their Chinese counterparts conveyed a readiness to accept India's permanent membership of the United Nations Security Council, though it was not willing to state this in black and white in the joint statement. Since then, however, as Indian prospects appeared to have diminished and the perceived power gap with China has widened, the Chinese sensitivity to Indian interests has also eroded.

Please click NEXT to read further...

A temporary phase of backlash for China

It is only in recent months that the tide has turned somewhat, when China has been facing a countervailing backlash to its assertive posture in the South China Sea and the US has declared its intention to 'rebalance' its security assets in the Asia-Pacific region.

There has been a setback to Chinese hitherto dominating presence in Myanmar and a steady devaluation of Pakistan's value to China as a proxy power to contain India.

At home, there are prospects of slower growth and persistent ethnic unrest in Xinjiang and Tibet. A major leadership transition is underway adding to the overall sense of uncertainly and anxiety.

We are, therefore, once again witnessing another renewed though probably temporary phase of greater friendliness towards India, but it's a pity that we are unable to engage in active and imaginative diplomacy to leverage this opportunity to India's enduring advantage, given the growing incoherence of our national polity.

I will speak briefly on Chinese attitudes specific to India and how China sees itself in relation to India. While going through a recent publication on China in 2020, I came across an observation I consider apt for this exercise.

The historian Jacques Barzun is quoted as saying:

"To see ourselves as others see us is a valuable gift, without doubt. But in international relations what is still rarer and far more useful is to see others as they see themselves."

It is true that through their long history, India and China have mostly enjoyed a benign relationship. This was mainly due to the forbidding geographical buffers between the two sides, the Taklamalan desert on the western edges of the Chinese empire, the vast, icy plateau of Tibet to the south and the ocean expanse to its east. Such interaction as did take place was through both the caravan routes across what is now Xinjiang as well as through the sea-borne trade routes across the Indian Ocean and South China Sea, linking Indian ports on both the eastern and western seaboard to the east coast of China.

Please click NEXT to read further...

Tibetan revolt gave strategic dimension to Indo-China differences

India was not located in the traditional Chinese political order consisting of subordinate states, whether such subordination was real or imagined. In civilizational terms, too, India, as a source of Buddhist religion and philosophy and, at some points in history, the knowledge capital of the region, may have been considered a special case, a parallel centre of power and culture, but comfortably far away.

During the age of imperialism and colonialism, India came into Chinese consciousness as a source of the opium that the British insisted on dumping into China. The use of Indian soldiers in the various military assaults on China by the British and the deployment of Indian police forces in the British concessions, may have also left a negative residue about India and Indians in the Chinese mind.

This was balanced by several strong positives, however, in particular the mutual sympathy between the two peoples struggling for political liberation and emancipation throughout the first half of the 20th century.

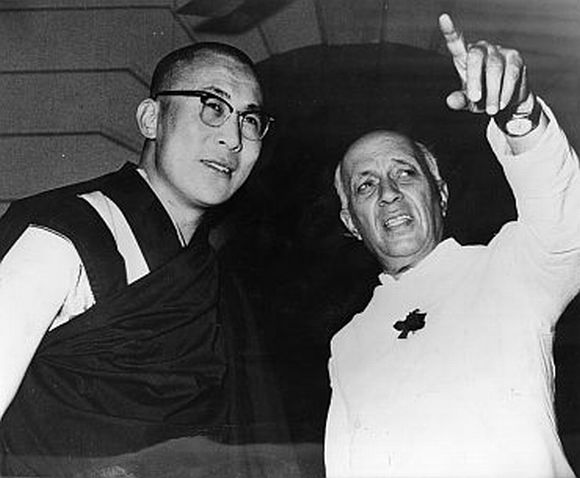

To some extent, these positives continued after Indian independence in 1947 and China's liberation in 1949 and were even reinforced thanks to Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's passionate belief in Asian resurgence and the seminal role that India and China could play in the process.

However, such sentiments were soon overlaid by the challenges of national consolidation in both countries and the pressures of heightened Cold War tensions. With Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1950, India and China became contiguous neighbours for the first time in history.

When the 1959 revolt in Tibet erupted and the Dalai Lama and 60,000 Tibetans sought and received shelter in India, the differences between the two sides on the boundary issue, took on a strategic dimension, as has been pointed out most recently by Henry Kissinger in his book On China.

Please click NEXT to read further...

China's 'overconfidence' phenomenon vis- -vis India

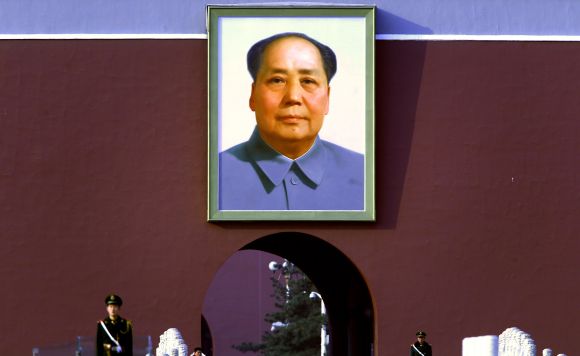

The 1962 war was not so much about the boundary as it was a Chinese response to a perceived threat to China's control over Tibet, however misplaced such perception may have been.

The comprehensive defeat of Indian forces in the short war and the regional and international humiliation of India that followed allowed China to conveniently locate India in its traditional inter-state pattern, as a subordinate state, not capable of ever matching the pre-eminence of Chinese power and influence.

Since 1962, most Chinese portrayals of India and Indian leaders in conversations with other world leaders or, more lately, in articles by some scholars and commentators, have been starkly negative.

An Indian would find it quite infuriating to read some of the exchanges on India and Indian leaders in the Kissinger transcripts.

In recent times, Chinese commentaries take China's elevated place in Asia and the world as a given, but Indian aspirations are dismissed as a 'dream'. There are repeated references to the big gap between the 'comprehensive national power' of the two countries.

India's indigenous capabilities are usually dismissed as having been borrowed from abroad.

In an interesting research paper entitled 'Chinese Responses to India's Military Modernisation', Lora Salmaan refers to the 'over confidence' phenomenon that characterises Chinese comparisons of their own capabilities vis-a-vis India.

She points outs that Indian claims of domestic production and innovation are frequently dismissed by Chinese analysts by adding the phrase 'so-called' or putting 'indigenous' or 'domestic' under quotes. She concludes that: "These rhetorical flourishes suggest elements of derision and dismissiveness in Chinese attitudes towards India's domestic programmes and abilities."

This dismissiveness also colours Chinese analysis of Indian politics and society. The usual Chinese refrain is that India is chaotic and undisciplined and does not have what it takes to be a great power like China. In an article entitled "Why China is Wary of India", the commentator Peter Lee relates an interesting story of what transpired at a Washington Security Conference:

"A Chinese delegate caused an awkward silence among the congenial group at a post-event drinks session when he stated that India was 'an undisciplined country where the plague and leprosy still exist. How a big dirty country like that can rise so quickly amazed us'."

Please click NEXT to read further...

The two stands in Chinese perception about India

Currently, there are two stands in Chinese perceptions about India. There are strong, lingering attitudes that dismiss India's claim as a credible power and regard its great power aspirations as 'arrogance' and as being an unrealistic pretension.

The other strand, also visible in scholarly writings and in the series of leadership summits that have taken place at regular intervals, is recognition that India's economic, military and scientific and technological capabilities are on the rise, even if they do not match China.

India is valued as an attractive market for Chinese products at a time when traditional markets in the West are flat. China is also respectful of India's role in multilateral fora, where on several global issues Indian interests converge with China.

I have personal experience of working closely and most productively with Chinese colleagues in the UN Climate Change negotiations and our trade negotiators have found the Chinese valuable allies in WTO negotiations.

In such settings Chinese comfortably defer to Indian leadership. I have also found that on issues of contention, there is reluctance to confront India directly, the effort usually being to encourage other countries to play a proxy role in frustrating Indian diplomacy.

This was clearly visible during the Nuclear Suppliers Group meeting in Vienna in 2008, when China did not wish to be the only country to oppose the waiver for India in nuclear trade, as it could have since the group functions by consensus.

China may have refused to engage India in any dialogue on nuclear or missile issues, but that does not mean that Indian capabilities in this regard are unnoticed or their implications for Chinese security are ignored.

It is in the maritime sphere that China considers Indian capabilities to possess the most credibility and as affecting Chinese security interests. These two strands reflect an ambivalence about India's emergence -- dismissive on the one hand, a wary, watchful and occasionally respectful posture on the other.

Needless to say, it is what trajectory India itself traverses in its economic and social development that will mostly influence Chinese perception about the country.

Please click NEXT to read further...

Analysing the Chinese prism

Additionally, how India manages its relations with other major powers, in particular, the United States, would also be a factor.

My experience has been that the closer India-US relations are seen to be, the more amenable China has proved to be. I do not accept the argument that a closer India-US relationship leads China to adopt a more negative and aggressive posture towards India.

The same is true of India's relations with countries like Japan, Indonesia and Australia, who have convergent concerns about Chinese dominance of the East Asian theatre. I also believe that it is a question of time before similar concerns surface in Russia as well.

India should be mindful of this in maintaining and consolidating its already friendly, but sometimes, sketchy relations with Russia. The stronger India's links are with these major powers, the more room India would have in its relations with China.

It would be apparent from my presentation that India and China harbour essentially adversarial perceptions of one another. This is determined by geography as well as by the growth trajectories of the two countries.

China is the one power which impinges most directly on India's geopolitical space. As the two countries expand their respective economic and military capabilities and their power radiates outwards from their frontiers, they will inevitably intrude into each other's zone of interest, what has been called 'over-lapping peripheries'.

It is not necessary that this adversarial relationship will inevitably generate tensions or, worse, another military conflict, but in order to avoid that India needs to fashion a strategy which is based on a constant familiarity with Chinese strategic calculus, the changes in this calculus as the regional and global landscape changes and which is, above all, informed by a deep understanding of Chinese culture, the psyche of its people and how these, too, are undergoing change in the process of modernisation.

Equally we should endeavour to shape Chinese perceptions through building on the positives and strengthening collaboration on convergent interests, which are not insignificant. One must always be mindful of the prism through which China interprets the world around it and India's place in that world. It is only through such a complex and continuing exercise that China's India challenge can be dealt with.

Sometimes a strong sense of history, portions of which may be imagined rather than real, may lead the Chinese to ignore the fact that the contemporary geo-political landscape is very different from that which prevailed during Chinese ascendancy in the past.

Merely achieving a higher proportion of the global GDP does not guarantee the restoration of pre-eminence.

Ancient China was not a globalised economy. It was a world in itself, mostly self sufficient and shunning the less civilized periphery around it. Today, China's emergence is integrally linked to the global economy. It is a creature of interdependence.

Similarly, today the geopolitical terrain is populated by a number of major powers, including in the Asian theatre.

A reassertion of Chinese dominance, or an assumption that being at the top of the pile in Asia is part of some natural order, is likely to bump up against painful ground reality, as it has since 2009, opening the door to the US rebalancing.

The recent reports of a slowing down of Chinese growth should also be sobering.

On the Indian side, the failure to look at the larger picture often results, by default, in looking at India-China relations inordinately through the military prism.

This also inhibits us from locating opportunities in an expanding Chinese market and in promoting a focus on the rich history of cultural interchange and the more contemporary pathways our two cultures have taken in fascinating ways. This covers music, dance, cinema, literature and painting. Chinese successes in development and its focus on infrastructure do have lessons for India which should be embraced.

And if China, for its own reasons, is willing to invest in India's own massive infrastructure development plans, why not examine how this could be leveraged while keeping our security concerns at the forefront? There are many areas of grey and it is for dispassionate strategists on both sides to explore and help shape a future for China-India relations that aspires to be as benign as it has been for most of the past.

TOP photo features of the week

Click on MORE to see another set of PHOTO features...