| « Back to article | Print this article |

Why democratic dividend must be reaped in Kashmir

Although the high voter turnout in the ongoing panchayat elections in Kashmir is not the end of all its problems, but if followed up with bold political steps and imaginative administrative measures, these elections can provide a platform for what an average Kashmiri needs during the summer of 2011 -- a chance to lead a regular socio-economic life, writes Sushant K Singh.

Despite vocal calls by various militant groups and separatist Kashmiri leaders, the first four phases of polling in the local body elections in Jammu and Kashmir have witnessed a voter turnout of nearly 80 percent.

Defying all expectations, almost 90 percent of the electorate turned up for voting in the separatist stronghold district of Kupwara during the first round of polling. The elections have, by and large, been peaceful.

This seems to be a significant turnaround after the violent protests last summer which brought the urban areas of Kashmir Valley to a standstill. Those protests were then portrayed by many commentators as an indictment of the Indian "occupation" of Kashmir.

Please click NEXT to read more...

A direct consequence of the decline in militancy in Kashmir

To understand the significance of these voting figures, consider this fact: Very few sarpanch and panch constituencies in Kashmir Valley actually went to the poll during the last panchayat elections in 2001. Polling took place in 208 out of 2,348 constituencies in Baramulla, 152 out of 1,695 constituencies in Kupwara and 53 out of 759 constituencies in Srinagar.

No poll was held in any of the 1022 constituencies of Badgam. The terrorist violence was at its peak in the state at that time, and the calls given by the Hizbul Mujahideen and the Hurriyat Conference, invoked enough fear in the minds of the candidates and the electorate to keep them away from the polls.

This turnaround, from 2001 to 2011, is a direct consequence of the decline in militancy in Kashmir. While militancy, which was essentially rural in nature, has been effectively pacified by the security forces, this has led to a change in tactics by the separatists.

Separatists' changed tactics isn't the complete face of Kashmir

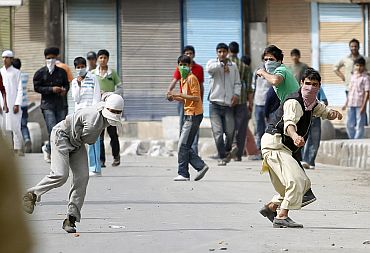

Since 2008, the separatists have shifted their focus to protests, shutdowns and demonstrations -- often involving organised stone-pelting against the security forces -- in the urban areas of Kashmir Valley. The urban bias of the media coverage, both national and international, has resulted in presenting a rather lopsided picture of the prevailing situation in Kashmir.

Many Indian commentators welcome the high participation of Kashmiris in the local polls as a vindication of Indian democracy and a proof of Kashmiris' disposition to be a part of the Indian Republic -- a de facto referendum in India's favour.

In contrast, most Kashmiri commentators, including the mainstream political leadership of the state, are guarded and often opposed to openly making any such proclamations. In fact, their stock answer is to dissociate these elections from the larger "Kashmir problem".

Many fear Centre's complacency

This somewhat unconvincing but partially true explanation is driven by two fears. Firstly, if the mainstream political leadership of the state claims victory after the high polling percentage in initial rounds, it may lead to a concerted blowback from the separatists and militants to derail the future rounds of polls.

It is indeed prudent to make any claims after all the phases of elections conclude successfully in June.

The second, and the more damaging apprehension, is based on the experience in the aftermath of successful assembly and parliamentary polls of 2008 and 2009 respectively.

After more than 60 percent voters participated in those elections, the Indian State claimed that all was well in Kashmir and sat on its haunches. No political or economic steps were initiated by the Centre to build upon the hope generated by those elections.

Many people fear the same complacency from the Centre again, if these elections are universally acclaimed to be a sign of a normal Kashmir.

Serious questions against 'true representatives' of Kashmir

It is not a secret that despite its public stance, the Jamaat- e- Islami is contesting these elections in a big way.

Even if it is conceded that people have not explicitly voted in favour of India by turning out in such vast numbers, by defying the unequivocal call of the separatists for poll boycott, they have certainly raised serious questions against those who claim to be the real representatives of the Kashmiris.

These elections vindicate the findings of the Freedom House -- UNHCR's Freedom Index for 2010 where Kashmir was rated higher on both Political Rights and Civil Liberties than Pakistan Occupied Kashmir and even Pakistan. PoK was in fact rated as "Not Free" by the Freedom House.

These elections provide an opportunity for India to educate the many international experts who tend to take the name "Azad Kashmir" (The Free Kashmir) for PoK rather literally, while pillorying India for its policies in Kashmir.

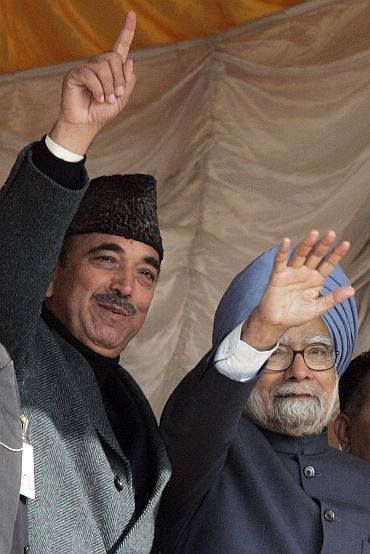

Challenge for Omar is to build upon this success

The challenge for (Omar) Abdullah is to build upon this success, devolve greater financial and administrative powers to these local bodies, politically engage the newly elected leaders, and closely involve these new stakeholders in governance.

The release of an additional grant of nearly Rs 1,000 crore, held back by the Centre due to absence of elected local bodies, will provide the state government with greater resources and flexibility to deploy these resources via these newly-elected local bodies.

It is nobody's claim that successful panchayat elections will solve the Kashmir problem. But, if followed up with bold political steps and imaginative administrative measures, these elections can provide a platform for what an average Kashmiri needs during the summer of 2011: peace, security and normalcy -- and a chance to lead a regular socio-economic life.