Photographs: Sumit Bhattacharya/Rediff.com

Sumit Bhattacharya listens in to conversations in poll-bound Kolkata.

"This kind of confrontational reports you write, always remember -- we have given you the right to do so," says an employee for one of the Communist Party of India-Marxist's many publications, to a journalist for a Kolkata daily at Alimuddin Street, home to the CPI-M headquarters, which, incidentally, has an unprotected wi-fi network.

"In 1972 (during the regime of Congress's Siddhartha Shankar Ray), everything you wrote would have to be approved by the government before publishing," adds the CPI-M reporter.

Meanwhile, a small art gallery in central Kolkata is holding an exhibition of paintings by Trinamool Congress chief Mamata Banerjee, the CPI-M's bete noir threatening to become its nemesis.

In no time, the gallery fills up with the likes of actress June Malya, artists Jogen Chowdhury and Subhaprasanna Bhattacharjee (both Trinamool sympathisers), cricket administrator Jagmohan Dalmiya, former state chief secretary Tarun Dutta, and others.

The exhibition, yet another ploy by the Trinamool to circumvent the Election Commission ban on microphones for political rallies till the school exams get over, hits headlines as celebs lap up Didi's 'art'.

"Chaitra ghurey gachhey (the season has turned)," says a West Bengal state government employee in a government agency office, discussing the upcoming election over tea and biscuits.

"It will be a tough fight. But what they were thinking -- that they would sweep the polls -- will not happen. If elections were held even six months ago, we would have been drubbed, but the season has turned," he says, in between rants about how his 'talented' son can't find a job.

"After all, he won't be able to labour away in a Marwari office, you see," adds the father.

...

Mamata 'magic', up close

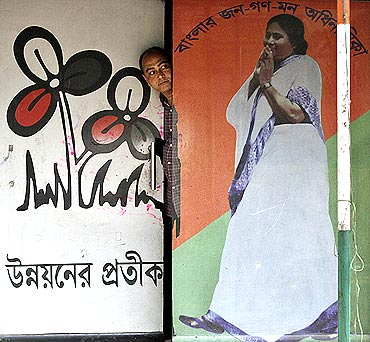

Image: A Trinamool Congress posterPhotographs: Rupak De Chowdhuri/Reuters

A day before, Garden Reach, Kolkata's dock area, is awash with green and red, the colours of the Trinamool Congress. Didi will walk through, on yet another one of her padayatras.

After frantic calls to Bobby Hakim, the local Trinamool MLA, we are allowed into the inner ring in the middle of the cordoned-off road. Then a black Maruti Zen arrives, and all hell breaks lose. Slogans are shouted, petals are showered, there is a near-stampede.

Didi emerges, clad in an ashen sari and with a sashay with the Trinamool slogan of Ma Mati Manush (mother, earth, mankind) embossed on it -- around her neck, and gets into crowd control.

"Boro korun, circle-ta boro korun (enlarge the circle)," she says as she pushes crowds back by just charging at the people, without touching anyone.

Photographers get into fistfights, one cameraman for a local daily screams at the top of his lungs at a police officer pushing the crowd back. We retreat.

On the footpath by the frenzied street, a middle-aged housewife begs to see the photographs we have managed to click.

"Didi is the only person who has consistently rushed to the voiceless's support, risking her life," she says -- as she looks at the blurred and hazy photographs of Didi -- about why she joined the Trinamool Congress a year ago.

"We are aware of everything," thunders state Housing Minister Gautam Deb, asked about the crowds at Didi's padayatras. "The biggest one had 25,000 people. We even know how many cars came from outside Kolkata It's easy to do padayatras. You don't have to talk to people, you don't have to answer any questions, just fold your hands and walk."

'You can't win Bengal by just winning in Kolkata, Howrah and North and South 24 Parganas'

Image: A CPI-M rally in Kamalgazi in South 24 Parganas districtPhotographs: Dipak Chakroborty

In Salt Lake, the now-upscale suburb of Kolkata, Gobinda Haldar is drunk on country liquor at midday, and desperate for conversation.

As he pedals his rickshaw, he rambles on without any asking: He lives in Dattabad (shanties along the arterial Eastern Metropolitan Bypass that sustain bhadralok Salt Lake with maids, drivers, watchmen, rickshawallahs, etc). His son rides a motorcycle, and is doing his BCom from a city college. His son has a girlfriend, and Gobinda thinks she is a nice girl.

Then Gobinda stops his rickshaw in the April Kolkata sun, and does a namashkar to a photograph of Subhash Chakraborty, the late CPI-M transport minister who was hugely popular in the area, which is plastered on a wall.

"Amar ma, (my mother)," he says without bothering about gender, going on to narrate how Chakraborty gave him the rickshaw for Rs 3,001, how he gave him Rs 30,000 to have a tiled roof in his house. Gobinda says he has land in Diamond Harbour, a distant Kolkata suburb. Why doesn't he go back there? "Why should I go back? I have a house. I need to pay only Rs 40 for it. And if I leave this house, there will be other problems."

What other problems, he will not say.

So, is he going to vote for the CPI-M? "Bolbo na, kano bolbo? Jodi boli CPM? Ki korbey (I won't say, why should I say? What if I say CPI-M? What will you do)," says the rickshawallah, suddenly defiant.

"Our internal calculations say we will manage to form the government," says a CPI-M party worker. "You can't win Bengal by just winning in Kolkata, Howrah and North and South 24 Parganas."

'Whoever goes to Lanka, becomes Raavan'

Image: Residential apartments under construction are reflected on the surface of a pond in KolkataPhotographs: Rupak De Chowdhuri/Reuters

A friend, who has become a father, narrates how his wife got the birth certificate for their little daughter Mahi -- named after the charismatic Indian cricket captain -- from the Kolkata Municipal Corporation.

His wife, says the friend, went to the KMC office and was told to come after 15 days and remind the clerks at the KMC office. She did that. Then they told her to come after another 15 days, explaining to her in detail about how many people had to clear the file.

She returned after 15 days, and was reprimanded for her impatience. "You obviously work in a private office," a woman clerk told her, "so you don't know that in government offices, this is the way it works."

Then, the clerk returned to singing songs from the 1970s hit Bengali suspense thriller Kuheli with a colleague. Exasperated, the new mother did an Anna Hazare. She squatted in front of the women's desk, and refused to budge until she got her daughter's birth certificate. She also called up an uncle who was a senior KMC official. She got the birth certificate in two hours after that.

The KMC is run by the Trinamool, Bengal's great hope for poriborton, or change.

"Jei jay Lankay, shei hoy Ravan, bujhlen (whoever goes to Lanka, becomes the demon king Ravan, get it?)," says Manas Haldar, a driver who lives in Keshtopur, another Dattabad-like shanty town near Salt Lake.

His village is 20 km from Nandigram, in the news for the violent theme of the elections. He says now if Nandigram's villagers who had fled during the violence try to return, "they" will chop off the villagers' hands, or smash their thumbs, so that they cannot be gainfully employed ever again.

"They assume that if you fled during the violence, you were with either the CPI-M, or with the other side, so either side will attack you," he says, adding how after India won the cricket World Cup, a villager who had gone to a nearby house to watch the match had his arms chopped off.

At a Kolkata neighbourhood bazaar, a middle-aged bhadralok is chatting up his neighbour. "Hawa to dichhe theeki," he says, "kintu bhalo hobey ki, (sure there is a wind blowing, but will it bring any good)?"

article