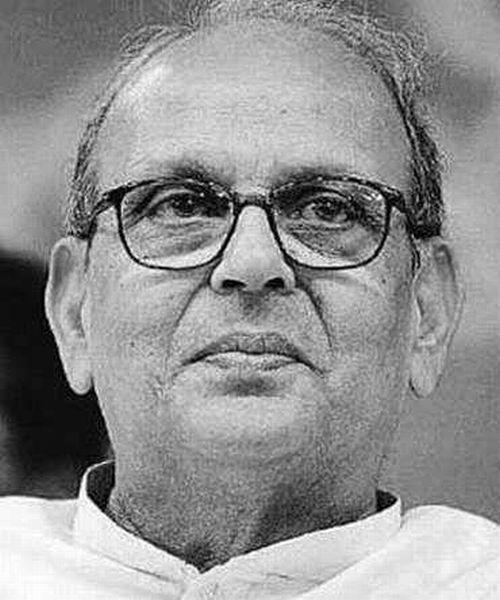

The common man had another hero 25 years ago in Vishwanath Pratap Singh, who sacrificed power in order to fight corruption before becoming the prime minister.

"I am standing before you in flesh and blood. If you want to physically assault me, you can do it now. You do not have to throw stones from a distance or shout at me from afar. Come here, do what you want. I am ready to face everything. I have the conviction that I am doing right when I seek to bring social justice and equality to this society and our country." With these words Vishwanath Pratap Singh, dressed in white, his eyes furious behind his large spectacles, moved from behind the lectern and to the front of the dais. He stood unprotected, daring potential attackers.

Venkitesh Ramakrishnan, then reporting for The Hindu, recalls the public meeting with searing intensity: "Until that moment, the predominantly Dalit-Other Backward Classes meeting was under constant brickbatting from a group of people who had taken cover in nearby buildings. Bottles and stones that came hurtling through the air had found two other important targets on the dais -- former Union ministers Sharad Yadav and Ajit Singh. Both suffered head injuries and were rushed to hospital for first aid.

It was at this moment that Singh stepped up. The silence hung in the air for what seemed an eternity; the assault too stopped. It was a rare instance of magical, emotive political oration that one had the privilege of witnessing. The meeting progressed without any further untoward incidents."

It was November 1990, days after Singh had been ousted as the prime minister of India. His action in accepting the recommendations of the Mandal Commission on job reservations for depressed classes had sent the country into a turmoil in which upper caste boys immolated themselves.

Alongside, Bharatiya Janata Party, having withdrawn its support to the Singh-led National Front regime, was sending waves of kar sevaks for a Ram Shila Pujan to lay the foundation for a temple in place of the mosque known as the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya.

Amid all this, Singh remained resolute, even when it cost him the prime ministership of the country. He would not compromise on his project of social engineering.

Please click NEXT to read further...

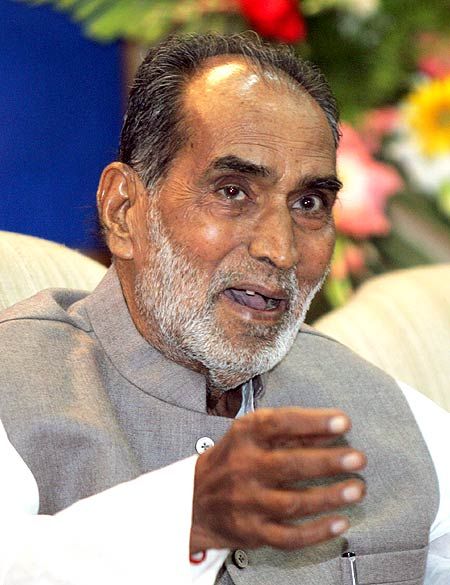

Singh was not a popular man. His direct rival -- in caste as well as power terms -- was Chandra Shekhar, also a Thakur, but much more outspoken, bluff and frequently rude in contrast to Singh's more deferential, reclusive personality.

Shekhar too had walked out of the Congress like Singh, and had gone to jail during the Emergency, but unlike Singh, had never flourished under the patronage of Sanjay Gandhi (whom he detested). So when Singh announced he was forming the Jan Morcha after his fallout with the then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, Shekhar was dismissive about 'Raja Saheb'.

But even Shekhar had to concede Singh had given up a lot in life. The politician, as a child, had been adopted by the raja of Manda, Raja Bahadur Ram Gopal Singh, and became heir to a vast estate. He was a lonely child guarded by two gunmen, with guardians and tutors to educate him. After a brief period of study at Colonel Brown Cambridge School in Dehradun, he went to Allahabad for higher studies and later, to Poona University.

Singh flirted with politics as a student, becoming president of the students' union at Udai Pratap College in Varanasi in 1947-48 and then the vice-president of Allahabad University Students Union.

It was in Allahabad that he became active in power politics, catching the eye of Sanjay Gandhi who recommended him highly to 'Mummy', Indira Gandhi, and getting him the chief ministership of Uttar Pradesh in 1980 on the strength of his innate honesty.

He resigned from that job two years later when a gang of dacoits created havoc, killing, among others, his brother. Singh said he didn't deserve to be in the job.

Please click NEXT to read further...

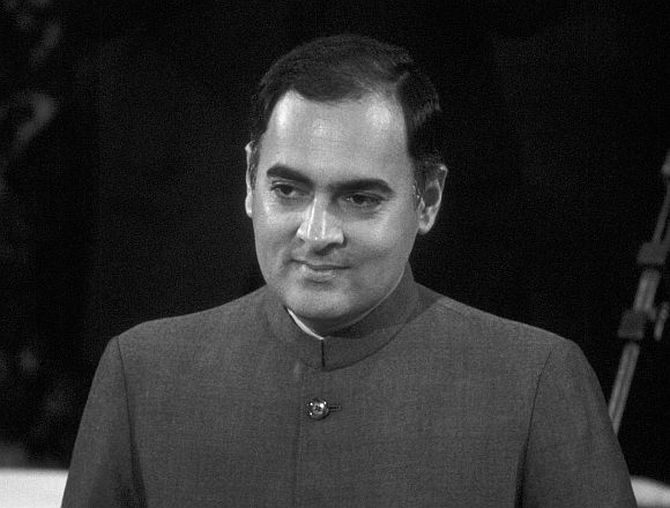

In 1984, Rajiv Gandhi became prime minister following his mother's assassination and consolidated his power with a massive electoral victory. This is when Singh began to be noticed in Delhi. Rajiv appointed him the finance minister.

Some of his interventions were unorthodox: he announced lower tax rates for gold, thus bringing down smuggling -- and for every kilo of smuggled gold apprehended by the Customs, a portion of the contraband was rewarded to them. But the big story of the 1980s and 1990s was corporate warfare, many allege, fanned by Singh because of the compulsion he felt to clean Indian politics.

In late 1986, Bhure Lal, then an officer in the Enforcement Directorate, informed Rajiv that Singh was investigating the illegal activities of many wealthy Indians, including Amitabh Bachchan and his brother, Ajitabh. Rajiv was confused: he had given no such directions and he was hearing this for the first time. It was suggested to him that this was Singh's personal agenda aimed at ridding himself of a rival in Allahabad (Amitabh Bachchan had contested the Lok Sabha election from Allahabad in 1984 and won).

Next came to light two sloppily forged letters allegedly written by the head of American detective agency (Fairfax) supposedly carrying out a probe into a corporate house and addressed to Lal. In the letters, the agency referred to its investigations into the bank accounts of the Bachchan brothers and the family of Rajiv's wife in Italy. They had a dramatic effect on the prime minister. He immediately shifted Singh from finance to defence.

Around the time, the first whispers started of something terribly wrong in the deal the government had signed to procure 155 mm Howitzer field guns from the Swedish company, Bofors. Singh, as defence minister, started an enquiry into another deal, that on the procurement of the HDW submarines.

A pressured Rajiv sacked Singh, who chose to resign from the Congress as well as the Lok Sabha. But the investigation into Bofors had aroused national passions.

"Gali gali mein shor hai, Rajiv Gandhi chor hai" (Everywhere there is talk of Rajiv Gandhi being a thief), was the dominant slogan of the time.

Please click NEXT to read further...

Singh had made corruption and his fight against it a household word. The unkind would say he made capital of his anti-0corruption crusader image. He launched the Jan Morcha on October 2, 1987, with disillusioned Congressmen like Arun Nehru and Arif Mohammed Khan. His pictures in the newspapers -- a self conscious, bare-chested Singh, legs tucked under him, sitting in an 'S' posture -- conjured up the images of Mahatma Gandhi.

Later, forced by political compulsions to accommodate leaders like Devi Lal and NT Rama Rao, he formed the Janata Dal and the rallying cry was: "Raja nahin faqir hai, desh ki taqdir hai (He’s not a king but a seer, he’s the future of the country)”.

The 1989 general elections were fought on the issue of corruption. Rajiv's party lost by a huge margin, but the government that came to power was besieged by a serious identity problem: was it left, right or centre?

Singh, the late Jansatta editor Prabhash Joshi once wrote, was like the sage Dadheechi, who enabled the devas to fight the righteous fight by making a donation of his bones with which to craft a weapon.

Please click NEXT to read further...

Unfortunately, as prime minister, Singh had to battle on a several fronts. Nor was he a man easy to understand. One battle was when the Larsen &Toubro controversy erupted in which state-owned Life Insurance Corporation was alleged to have sold its shares to private parties to assist in their takeover of the company.

Singh put a stop to this. When the matter moved to court, DN Ghosh, former chairman of State Bank of India, became chairman of L&T, replacing the private-sector chairman.

Journalist Mark Tully says of Singh: "He was neither liked nor trusted by his colleagues because he went against the grain.

Inevitably, he was accused of hypocrisy. There were those who said he had resigned as chief minister of Uttar Pradesh because Indira Gandhi was about to sack him -- something he always denied. Then again, his campaign against tax evasion and corruption in defence purchases was seen as a ploy to launch himself as a rival to Rajiv.

He confounded his critics by never seeking office after he was ousted, but remained in public life by campaigning for causes he believed in. He was shy, with a slightly nervous laugh, but to those who knew him he fully justified his public image of honesty, being open to discussion of any aspect of his career and willing to accept criticism."

Please click NEXT to read further...

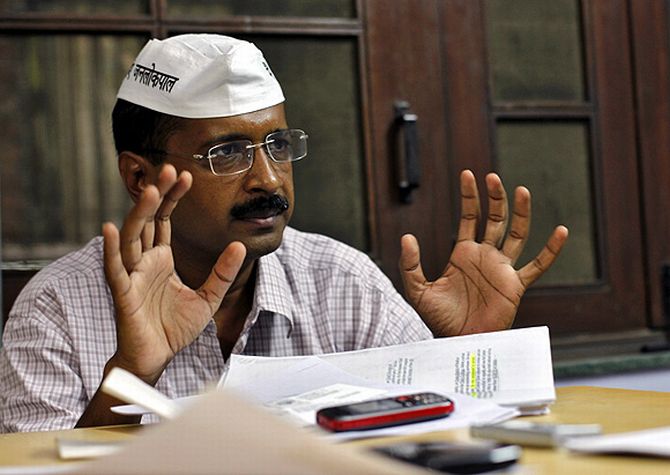

The parallels with current events are inevitable: just as Singh represented the underclass, empowered the subaltern and believed that it was more important to be honest than to be prime minister, there is another person with similar views on the horizon: Arvind Kejriwal.

The difference, however, is that Singh believed in rising above stereotypes, addressing complex ideological challenges in Indian society. We are yet to hear any of that from Kejriwal and his Aam Aadmi Party.

Click on MORE to see another PHOTO features...