| « Back to article | Print this article |

Naxal movement has shown tremendous grit

From an agrarian movement to 'Jan Militia', the Naxal movement has assumed worrying proportions for the State today. Veteran cop Mahendra Kumawat, in a write-up in the Seminar magazine, assesses the Naxal phenomena and states that negating the romantic appeal of Maoism and convincing the teeming millions that their problems would be addressed could lead to a lasting solution to the issue.

In its 43 years of existence, the Naxal movement has shown tremendous grit and resilience. What began as a small agrarian rebellion against the local landlords at Naxalbari in West Bengal is now a full-blown insurgency, at least in Bastar and parts of Orissa and Jharkhand.

The Union home ministry reports that their influence spans 223 districts across 20 states, although of course, the degree of activity varies vastly.

The situation has become grave owing to the recurring attacks by the Maoists against the symbols of our democratic state -- such as the elected representatives, electricity stations, transmission towers, railway tracks, jails, armouries, police stations, schools -- and the killing of a large number of security personnel, suspected police informants, and so on.Click next to read on...

Naxal violence increased threefold in 2009

The merger of People's War Group and Maoist Communist Centre in September 2004 led to the formation of a new united outfit called the Communist Party of India-Maoist.

The programme of the CPI-Maoist, christened as New Democratic Revolution affirms, 'The revolution will be carried out and completed through armed agrarian revolutionary war, that is protracted people's war with armed seizure of power remaining as its central and principal task.' It also 'supports the struggle of the sub-nationalities for self determination, including the right to secession.'

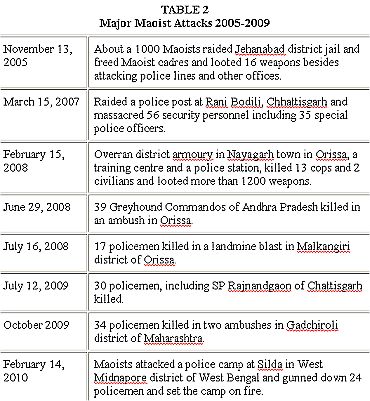

This merger has given a new impetus and momentum to the Maoist insurgency. The increased intensity of violence, coupled with the spatial growth of the movement has added a new dimension to the challenge being faced by the state. While 100 policemen died in Naxal violence in 2004, the causality figure increased threefold in 2009 with more than 300 security force personnel killed in ambushes and landmine blasts. (Table 1)Precision attacks by Naxals are alarming

What has alarmed the State are the well-planned and well-conducted attacks carried out with military precision.

To recount a few: On November 13, 2005, about a thousand Maoists raided the Jehanabad district jail. They freed 389 prisoners and simultaneously attacked police lines and offices of the district administration and looted weapons.

The attack discredited the State and exposed ineptitude of the state administration, including the police.

On the night of March 14, 2007, in a stunning attack on a police post at Rani Bodli in Chhattisgarh, the Maoists massacred 55 policemen and special police officers and injured 12 others.

Since then a number of such attacks have been carried out in Orissa, Jharkhand, Bihar and Maharashtra, and most recently in Midnapore (WB) claiming the lives of 24 policemen.

Maoists have R&D units for latest weapons

A number of factors have contributed to the growing influence of the Maoists and their increased intensity of violence and stepped up mass mobilisation.

First, the merger of the two most potent groups -- the PWG and the MCC -- has given synergy to the new outfit in terms of strength, capability, and resources, both human and material, for launching attacks on the security forces. The combined strength of the CPI-Maoist is estimated to be 15,000 armed cadres, which is huge compared to the 3,000 militants in Kashmir at the peak of the militancy.

Second, the merger has provided a large swathe of India -- from Bihar to Andhra Pradesh -- for the Maoists to move, both for operations and safe havens. While state police forces are restricted by jurisdiction and a lack of interstate coordination, the Maoists are not. This gives them an upper hand and the ability to carry out audacious attacks across the states at will.

Third, while the Naxals in the late 1960s used bows, arrows, axes, pistols and small bombs to annihilate 'class enemies', the Maoists (Naxals in their new avatar), have an array of sophisticated and lethal weapons which include AK-47s, light machine guns, INSAS rifles, self-loading rifles, grenades, mortars, rocket launchers, among others.

These have been acquired through raids on police armouries and snatching of arms of the policemen killed in ambush, apart from the supply of weapons by the LTTE and Nepalese Maoists. The easy availability of explosives in the Red Corridor has facilitated the laying of landmines to kill troops with most devastating effect. The Maoists have R&D units which fabricate and upgrade weaponry, including improvised explosive devices, which have added to the strike power of the Maoists.

Maoism has a romantic appeal

Consequently, the People's Liberation Guerrilla Army is being upgraded to the People's Liberation Army. To ensure direct participation of the masses in armed activities, the Maoists have also been attempting to promote armed mass action as a part of their military campaign.

Fifth, the recent attempts by the government to bring in industries to the mineral rich areas of Chhattisgarh, Orissa and Jharkhand has led to a displacement of tribals and their intensified exploitation, raising serious issues of land acquisition mechanisms, compensation and so on. The Maoists have been effectively able to exploit these problems of the tribals for their own political objectives.

Sixth, the lack of consensus among the states about the Maoist problem is reflected in a lack of coordination in dealing with the challenge. The Naxals have taken full advantage of this situation.

Seventh, the mineral rich areas of central India which are also the pockets of Naxal influence provide them with large funds by way of extortion and levies from contractors, businessmen, transporters, siphoning off of development funds, voluntary contributions and looting of treasuries and banks. These funds, estimated to the tune of Rs 1,000 crore a year are being utilised for increasing their cadre strength, procurement of arms, R&D work, information and publicity, besides running the organisation.

Eighth, at times when counter-insurgency operations are carried out, the human rights of the locals are not respected and that proves counter-productive. Lalgarh is a case in point where police operations ended up creating more Maoists in the form of 'Jan-militia'.

Ninth, Maoism has a romantic appeal, especially to the disadvantaged sections of society and a few intellectuals, given the widespread perception about the effectiveness of a possible totalitarian government that the Maoists intend to form. Sympathetic support of Naxalism from left-wing intellectuals and the human rights community also accord some legitimacy and glamour to the movement.

Mao's dictum has been the credo of the Naxals

Lastly, the 'positive' contribution of the Naxal movement to the Adivasis and Dalits, such as curbing feudal practices and social oppression, confiscation and redistribution of surplus ceiling land, higher agricultural wages, reduction of stranglehold of landlords, moneylenders and contractors, protection from harassment by forest department officials and the police, among others, has given the Maoists an image of being 'saviours'.

This has significantly contributed to the growth of the movement into newer areas. Clearly, the activists who support this movement do not realise that if a totalitarian communist government does assume power this illusion will not materialise, for historically they have only led to the death and impoverishment of millions.

Since the beginning, Mao's dictum -- 'power grows out of the barrel of a gun' -- has been the credo of the Naxals. Their principal objective is to capture state power through force.

In view of this philosophy and use of violence to achieve their objectives, the Naxal movement has always been considered a serious security threat by the state and so the strategies evolved to contain it have been security-centric, except in West Bengal and Kerala, where during the first phase of the movement in the 1960s, progressive land reforms also played an important role in dealing with it.

The salient features of the current policy of the government of India are: (i) deal sternly with the Naxalites indulging in violence; (ii) address the problem simultaneously on political, security and development fronts in a holistic manner; (iii) ensure interstate coordination in dealing with the problem; (iv) give priority to faster socio-economic development in the Naxal affected prone areas; (iv) supplement the efforts and resources of the affected states on both security and development fronts; (v) promote local resistance groups against the Naxalites; (vi) use mass media to highlight the futility of Naxal violence and the consequent loss of life and property; (vii) evolve a proper surrender and rehabilitation policy for the Naxalites; and (viii) discourage affected states from any peace dialogue with the Naxal groups unless the latter agree to give up violence and arms.

There are no young policemen to take on the armed guerrillas

The Naxal movement has continued to grow in spite of the comprehensive policy due to the poor implementation of the schemes by the states. The administrative and security establishments in the states have lacked commitment, dedication and, above all, competence to deliver.

There has been decades of neglect of the state police forces in the states worst affected by the Naxal problem. The police-population ratios of the affected states are very low. As against the international norms of 250 policemen per 100,000 and national average of 143, Bihar is a low 79, Jharkhand 164, Chhattisgarh 134, UP 94, and Orissa 100. Policemen in these states operate under abysmal working conditions with little technical support, antiquated weapons and hardly any training in jungle warfare.

In fact, Bihar has the dubious distinction of not even having a training academy for its officers. Moreover, there has been no fresh recruitment in Bihar and Jharkhand for almost 14 years, which means there are no young policemen to take on the armed guerrillas who are young and agile.

In such a situation, after every major Naxal attack, the standard response of the chief ministers of these states has been to ask for more central forces. The central forces, raised for different mandates like guarding our borders, are trained differently and find themselves at a disadvantage given their ignorance of the terrain and lack of intelligence.

Tribals are bearing the brunt of insurgency and counter-insurgency

The state's encouragement of vigilante groups such as Salwa Judum as part of the counter-insurgency strategy has only led to fratricidal war between the tribals. Maoists and Salwa Judum members have killed each other, often brutally.

It is a sad paradox that it is the tribals who are mainly bearing the brunt of insurgency and counter-insurgency and are dying in hundreds when both the state and Maoists claim to be fighting for them. This approach of the state has come under severe criticism not only from the civil society but also the Supreme Court of India and has proved to be counterproductive.

In spite of a host of development schemes such as National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, National Rural Health Mission, Sarva Siksha Abhiyan, Integrated Child Development Scheme, Backward Tribes Initiative and plethora of legislations, the condition of adivasis in Naxal affected states remains appalling.

Displacement, and in some cases multiple-displacement, of tribals without proper resettlement and rehabilitation due to mining projects and industry has further compounded their misery. In Bihar 3.5 per cent of the land owing community continues to own large chunk (33 per cent) of the land, placing a question mark on the sincerity of successive governments about land reforms.

The Maoist challenge is complex and formidable

On the other hand, the state, despite the policy to use mass media to highlight Naxal violence, and with all means to do so, has done precious little to convince the tribals and activists about the advantages of a democratic republic over a totalitarian regime which the Maoists seek to establish by force.

The Maoist challenge is complex and formidable. It cannot be contained by security measures alone. The state must follow a multi-pronged strategy. While the armed Maoists will have to be subdued by the security forces, though with a human face, the state must end the multifaceted exploitation of tribals and Dalits and make them partners in progress. Only inclusive growth will stem the tide.

The human rights activists and left-wing intellectuals must be engaged in debate and convinced that, notwithstanding all the shortcomings, we are a democratic republic which can redress problems of the teeming millions with freedom, liberty and equality and not the warped and failed ideology which talks in terms of armed insurrection and violence which has been junked even in the county of its origin. The state must wrest back the lost territory from the Maoists. But only when it can successfully wrest back the hearts and minds of the masses, would there be a lasting solution.