| « Back to article | Print this article |

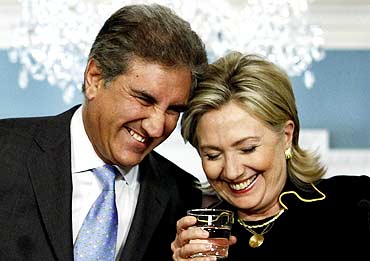

'US had two separate policies for Pak'

Nawaz is director of the South Asia Centre at the Washington, DC-based Atlantic Council, and author of Crossed Swords: Pakistan, its Army, and the Wars Within.

In an interview with rediff.com's Aziz Haniffa, Nawaz said for the first time, the parallel military track which led to much distrust between Washington and Islamabad, would be a thing of the past.

How significant is the fact that for the first time, a Pakistani army chief participated in the US-Pakistan strategic dialogue, which has traditionally been a dialogue -- for decades -- between the State Department and the Pakistani foreign ministry?

It's a good omen because it means that there won't be a parallel track -- military to military relationship -- which was often the criticism in the past. That the US had two separate policies in effect, one that was part of the military to military relationship and the other that was the political.

'ISI chief reports directly to the Pakistan PM'

The military obviously plays a very critical role in all aspects of foreign policy, particularly dealing with Afghanistan, with Kashmir and the nuclear issue. These are the three main issues for a couple of decades now -- the military has had a very powerful role to play.

Inter Services Intelligence chief General Ahmad Shuja Pasha, who recently received an extension, was also an integral part of the strategic dialogue.

In terms of General Pasha's involvement, he has been here (in Washington, DC) before with the prime minister (Yousuf Raza Gilani) or the foreign minister (Shah Mahmood Qureshi). And, because the director general of the ISI reports to the prime minister, he has a direct relationship with the civilian government.

US Special Representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan Richard Holbrooke defended Kayani's inclusion, saying, 'If we have a strategic dialogue in our country, we are going to include the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff or some other representative. So we are very pleased that General Kayani is part of this delegation. We think that it's one country, one government, one team.' Isn't this a clear acknowledgement that the army calls the shots in Pakistan?

I believe it avoids any second guessing. It avoids confusion and adds a certain element of clarity to the discussions -- so that nobody can say later on that he or his institution wasn't part of the discussion.

'Pak govt has not come up with a war plan'

Can't it be argued that the US is basically saying that while there is a civilian government in place, it's really the Pakistani military that matters and Washington has got to deal with it to further not just the US-Pakistan strategic dialogue, but Washington's own interests in the region -- the so-called US-led war on terror?

This is reflecting the situation on the ground in Pakistan -- that the military is organised and disciplined and powerful and is playing a lead role in the fight against the insurgency.

Also that the civilian government has obviously not been well organised and as strong in coming up not just with a strategy, but with a war plan.

And, that I hope will emerge now because as they get to discussing these issues with the military, it will be important for the civilians to take charge.

In terms of the dialogue itself, the fact that it's going to be broad-based, isn't there a likelihood that it could miss out on the things that really matter in the immediate context -- forging ahead in tangible terms of the core issues?

It's a broad-based dialogue because you have to look at security, you have to look at economy, at trade, so many issues. And that's important.

You can't simply only have a dialogue on the military aspects alone. So, they'll have to look at regional issues, bilateral issues, all of them come into play. So, it has to be all encompassing, and that is the expectation.

'For the first time, the US has strategic ties with both India and Pak'

Holbrooke also asserted that this dialogue with Pakistan is not taking place at India's expense, and referred to the strategic dialogue that the US has with New Delhi too. But you don't have the Indian Army chief and intelligence chiefs being major players in such a dialogue.

For the simple reason that India is not a frontline State. If India was bordering Afghanistan, India's military would obviously have the same kind of relationship with the US military that the Pakistani military does. I don't know what the concern in India is.

It's very important to recognise that for the first time in history, the US has strategic relationships with both India and Pakistan and it's important for it to use that relationship behind closed doors to convince both of these countries to work with each other and to avoid making Afghanistan a cockpit.

So if that happens and particularly if the Indian and Pakistani dialogue proceeds to at least return to the level at which it was under (former Pakistan president Pervez) Musharraf, then there is hope that India and Pakistan will be able to work together in Afghanistan too.

Last fortnight, India's Foreign Secretary Nirupama Rao made it absolutely clear that there would be no return to the composite dialogue unless and until Pakistan totally eliminates the terrorist infrastructure within its territory. Evidently, it was also a message to the powers that be in the US who have been encouraging a return to the composite dialogue.

Rao also made the point a couple of times that what the Government of India is saying and doing is what the people of India want. However, the polls done by The Times of India and the Jang group in Pakistan -- the newspaper group that runs The News also -- indicates that 70 percent of people in India and Pakistan that were polled want peaceful relations with the other country. So there seems to be a disconnect between what the bureaucrats are saying and what the people are saying.

I believe this is an opportunity for a statesman like Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to take the lead and revive the level of discourse that had occurred with General Musharraf, who seemed the most improbable person to reach such a level of understanding with India.

The most improbable person because he was an army chief and he was also the army chief on whose watch the two countries nearly came to war because of Kargil. So if he could shed the past and agree to work with India, I think it should be possible for the elected leaders of India and Pakistan to work together -- the civilian leaders.

It's an opportunity that should not be missed, rather than getting into the weeds and re-fighting all the old quarrels of the past.

It's a great opportunity for the leaders of India and Pakistan to sort of leap over these hurdles.

'32 or 34 of India's strike airfields are aligned against Pak'

But there is a veritable consensus among the experts and analysts -- and even the Pentagon and the US intelligence -- that Pakistan still perceives India -- and not the internal turmoil -- as the primary threat.

I believe Pakistan recognises at all levels now -- both civilian and the military -- that the immediate threat to Pakistan is internal. But that doesn't mean that the potential of India (as a threat) has been totally removed. That won't happen till a number of things happen, and one most definitely has to be some kind of a change in the posture of the Indian military vis-a-vis Pakistan.

If currently nine corps are poised along the India-Pakistan border that gives a very different signal to the Pakistani military.

They are not going to lower their guard. I believe something like 32 or 34 of the strike airfields are also aligned against Pakistan. So that is the potential that worries the Pakistan military, because their job is to defend Pakistan.

Now if you remove the causes of any conflict, and if you remove the causes of hostility, then it wouldn't matter where they are. But, for the time being, because a number of these issues remain unresolved, this obviously does concern the Pakistanis. That doesn't mean that they don't recognise the immediate danger from within.