| « Back to article | Print this article |

'The day govt can enter Tadmetla Naxal movement will be over'

On Sunday, six personnel of the Central Industrial Security Force have been killed in a Maoist attack in Kirandul near Dantewada in Chhattisgarh. The incident comes days after the Chhattisgarh government secured the release of Sukma district collector, Alex Paul Menon, who had been abducted by Naxals.

Chief Minister Raman Singh tells Devjyot Ghoshal that the pressure created by the state's security apparatus in the last few years has created a situation where the development agenda can now take centre stage. But the actual turnaround in the situation will only come in the next three-four years.

The undivided Bastar district was a massive area covering some 39,000 sq km. Is there an issue of historical administrative neglect when it comes to the growth of the Naxal movement in Chhattisgarh and has the division of Bastar into seven districts helped improve the situation?

There is a huge backlog. (Undivided) Bastar could not have been administered by one or even three collectors. The collector of Sukma (the incumbent Alex Paul Menon was recently abducted by Naxals) can think of going to Chintalnar and Chintagufa today, but it was unimaginable that a collector, or a patwari, of Bastar would go that far earlier.

Now, the area under the collector of Sukma is such that he/she, despite the risks, will go to the interiors. It is the same in Dantewada, too.

Tadmetla, for instance, is like the national capital of the Naxals, and the day we (the government) can enter there, the Naxal movement will be over. The Central Reserve Police Force has already reached Chintalnar, which borders Tadmetla, and that shows how far we have got.

Right now, only the (paramilitary) forces have got there. Slowly, we will be able to ensure development in these areas, too. People are gradually finding about health care and education, and we have also been able to take our public distribution system there.

Some of these places had panchayat buildings, schools and anganwadis, but the Naxals destroyed the infrastructure, blew up roads and then mined them. We will have to build the infrastructure first.

'Naxals are scared of education'

Some are concerned that there is much focus on security and forces are being piled up. How do you view it?

In about 40,000 sq km, you can calculate, even if we deploy thousands of troops, they will be lost. For stretches up to 150 km in some places, there are no (police) outposts. If bridges, roads and schools are blown up by the Naxals, you need the presence of security forces to rebuild these. The residential schools are safe because there is a deployment in the surrounding areas. If the forces are withdrawn, no one will be able to stay or work in these areas.

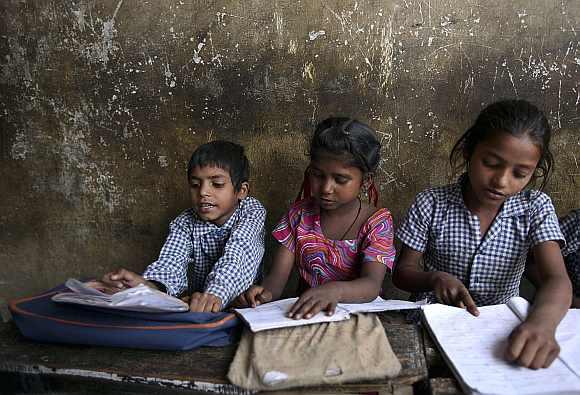

Education has been the focus of your government in recent years but there is a problem with finding enough teachers. What is your strategy?

We are now creating large, residential school. That is our long-term strategy. The Naxals are scared of it, which is why they want to blow them up. They are scared of education.

We are trying to bring in highly trained teachers. The problem is with the science subjects and English, as enough teachers for these are not available locally, and those from outside the state do not necessarily want to come. For the large residential schools, we are also looking at implementing centralised distance learning.

But the manpower problem isn't just limited to education; it is also impacting health care services. In some affected districts, less than 10 per cent of the allocated MBBS doctors are actually available.

We are now paying up to Rs 1 lakh (per month) to get doctors into these areas. Earlier, some districts did not even have a single doctor. Now they are getting paid more than what some earn even in Raipur. We have paramedics, including those trained under the three-year programme, who are working in the affected areas. We are trying to fill up all the empty posts.

But for conducting surgeries and specialised areas such as gynaecology, we need trained, qualified doctors. However, this is a shortage that the entire country is facing and not Chhattisgarh alone. This is why we are mobilising 108 -- the emergency response ambulance service, Sanjeevani -- in these areas, so that patients can be easily moved to medical facilities where they can be operated on.

'Security pressure will help prioritise social schemes'

During the Salwa Judum movement and the period immediately after, there was an inordinate focus on security in the Naxal-affected region. Is the focus now shifting towards ensuring development in these areas?

As far as Salwa Judum is concerned, it was a representation of pent-up anger against the Naxals. It was their (tribal population) own movement. No government, neither the Bharatiya Janata Party nor the Congress, can start a revolution there. No one has the strength to provoke people in the Naxal-affected areas. The angst is still there, but it isn't identified as Salwa Judum anymore.

Till the presence of the government, through police stations and outputs, is not strengthened in those areas, we can't do a whole lot more because people are continuing to live in fear of the Naxals.

Initially, our police strength was so weak that we had 20,000-25,000 policemen who didn't even know what guerrilla warfare was, and if you sent them to the frontlines, what would they be able to do? We created a jungle warfare school, improved the training and slowly the casualty figures are now coming down. Till you don't create this security pressure, no one will be willing to sit down for dialogue or discussions.

This problem needs time to solve. You can't enter into the affected areas, shoot the Naxals and come out overnight. They live among the common people, and are difficult to identify. I think after the pressure that we have created in the last six-seven years, we will now be able to give priority to all the social sector schemes.

'There will be a huge turnaround in Naxal situation in 3-4 years'

Yet, in implementing development programmes, many of those directed from the Centre, your district collectors have to fight the system as much as fighting the Naxals?

You can't think of Punjab and Haryana, and design programmes that will work in Bastar, Dantewada and Bijapur. After Jairam Ramesh became the rural development minister, some programmes have been modified. In education, I've said it doesn't make sense to open schools every three, five or seven km. We need large, residential schools here, instead.

In making roads, for instance, not only do you need the presence of security, but also flexibility in the tender process, which is now coming through. We need de-centralisation if proper implementation has to take place.

Almost everyone concedes the fight against Naxalism is a long one. But given your experience in Chhattisgarh, how protracted do you think this struggle is likely to be?

Twelve years ago, Andhra Pradesh started dealing with the problem, and now there is an 80 per cent drop in violence in the state. For us, given the work that we have done so far, there will a huge turnaround in the situation in another three-four years.

TOP photo features of the week

Click on MORE to see another set of PHOTO features...