Photographs: Archana Masih/Rediff.com

He regaled me with stories about the various occupants of the PMO during his decade and a half there, about their egos and their foibles. He gave me valuable advice on how I should discharge my duties both as media advisor and speech-writer that stood me in good stead throughout my four-and-a-half years in the job.

...

For a man who had the trust of the prime minister, he lived in a two-room DDA flat

Image: A policeman keeps vigil outside Parliament in New Delhi, inset, H Y Sharada PrasadPhotographs: B Mathur/Reuters

The era when one could happily say that the PM's media advisor kept in touch with just five top English newspapers was long gone. Not only had Indian language television and print become more important, but even English language television and print had burgeoned and the internet had arrived.

...

Nowhere has there been a bigger boom in media than in India

Image: The media covers the terrorist attack at the Taj Hotel in MumbaiPhotographs: Desmond Boylan/Reuters

'With the rapid growth of media in recent times, qualitative development has not kept step with quantitative growth. In the race for capturing markets, journalists have been encouraged to cut corners, to take chances, to hit and run. I believe the time has come for journalists to take stock of how competition has impacted upon quality. Consider the fact that even one mistake, and a resultant accident, can debar an airline pilot from ever pursuing his career. Consider the case that one wrong operation leading to a life lost, and a doctor can no longer inspire the confidence of his patients. One night of sleeping on the job at a railway crossing, an avoidable train accident, and a railway man gets suspended. How many mistakes must a journalist make, how many wrong stories, and how many motivated columns before professional clamps are placed? How do the financial media deal with market moving stories that have no basis in fact? Investors gain and lose, markets rise and fall, but what happens to those reporters, analysts, editors who move and make markets? Are there professional codes of conduct that address these challenges? Is the Press Council the right organisation to address these challenges? Can professional organizations of journalists play a role?'

...

Integration of business with politics is shaping news media

Image: A man reads a newspaper during a shave in KolkataPhotographs: Rupak De Chowdhuri/Reuters

But it is not just the integration of businesses that is having an impact on media. It is the integration of business with politics and politics with business that is now shaping news media, and not just at the national level.

...

The nexus between politics, business and media is very close

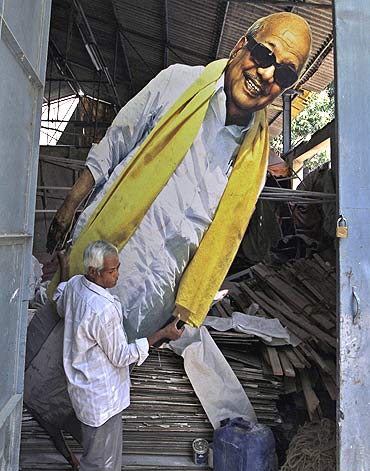

Image: The DMK as a party has acquired enormous control over the entire media businessPhotographs: Babu/Reuters

Indian media needs a framework of reference to define what constitutes a competitive structure, what policies amount to being restrictive trade practices, how can such practices be curbed and who curbs them. Has the time come for the Competition Commission of India to consider a framework for regulation of cross-media ownership, predatory pricing and other restrictive and unethical business practices, including the phenomenon of 'paid news', in the media and entertainment industry?

...

Professional editors are becoming an endangered species

Image: Former telecommunications minister A Raja is being investigated for the 2G scam and is in prisonPhotographs: Adnan Abidi/Reuters

Editors, who demand accountability from elected representatives of the people, are often quite happy to censor dissent and straitjacket diverse opinion within their own organisations. When such tyrannical editors are also owners or CEOs of their media establishments there is no internal court of appeal for a journalist.

...

The media may be turning populist

Image: Social activist Anna Hazare rests during a 'fast unto death' campaign in New Delhi April 8, 2011Photographs: Parivartan Sharma/Reuters

What is worrying, however, is that in response to such public anger and cynicism the media may be turning populist -- a standard response of a politician -- in an attempt to ingratiate itself to its critics. This too is a dangerous trend. Media populism is in part a response to public anger and, paradoxically, a response to public disdain and indifference.

...

Indian media must look within, introspect and rediscover

Image: Indian Sikh pilgrims wave to onlookers during the Baisakhi festivalPhotographs: Mohsin Raza/Reuters

That would be the best tribute we can pay to a great Indian, a truly renaissance man, a liberal scholar, a non-argumentative Indian like Sharada Prasad!

Dr Sanjaya Baru is the editor of the Business Standard

article