| « Back to article | Print this article |

The Mahakumbh: Where everyone is invited

The Mahakumbh to me has always evoked memories of what an older era of Hinduism must have been, its strength in its diversity and acceptance, its spirit resting not in priests but in individual bhakti, a faith totally alien to intolerance and bigotry, says CNN-IBN Deputy Editor Sagarika Ghose.

The waters of the Sangam are not deep but icy and electrifying. The long processions of Naga babas and priestly orders are richly colourful, spectacular, a satisfyingly 'Oriental' freak show for the Western media.

On the sandy banks of the river the pilgrim or kalpvasi undertakes his austere pilgrimage, performing small household rituals alone or surrounded by family.

The Mahakumbh is a paradox of the spectacular and the ordinary, of the mystical and the humdrum. For some the Kumbh is simply a large dusty village fair, for others it is a transcendental experience with a river, a moment of surrender and remembrance.

My tryst with the Kumbh began twelve years ago when I went to cover the Mahakumbh of 2001. Then as now I remain fascinated.

Makar Sankranti dawns foggy and dark on the banks of the Sangam. The gigantic human procession that proceeds for the shahi snan is in itself an uplifting experience: In a massive crowd one becomes an individual, with one's own unique relationship with the river and the sun.

The order of the bath is a slowly unfolding canvas of fantastical images: The different akharas of sadhus -- among others Mahanirvani, Niranjani and Juna -- bathe according to the order of their importance.

The Panchdasnam Juna Akhara are called the Hell's Angels of the Kumbh, performing tricks with their penises and dreadlocks, and dancing with their trishuls held aloft. When the Juna Akhara roars down towards the Sangam to bathe, crowds of pilgrims scatter in fear and awe.

Please click NEXT to see more...

Rent-a-Naga is a thriving business, some Nagas are educated professionals

The origins of India's naked ascetic sanyasis are shrouded in mystery. Most accounts say they were originally the fighting force of the priestly orders, taking the vow of brahmacharya in order to dedicate their lives to the protection of the priests.

G S Ghurye writes in his book Indian Sadhus that the naked Nagas are remnants of private armies that temple establishments maintained for protection and privacy.

The British outlawed the Nagas and since then they have become museum pieces from the distant past.

Today the Nagas -- and particularly the Juna Akhara -- have fallen into some disrepute with allegations of criminality being levelled against some of the babas. But the Mahakumbh is still their stamping ground, the place where they believe they regain some of the primacy in society that they may have had centuries ago.

Lines of ashrams and akharas stretch for miles in the 6,000 acre Kumbh Nagar. The entry to each akhara proudly announces its name in brightly painted banners. Inside the tented camps, sadhus sit around the dhunis (fireplaces) smoking ganja (marijuana) from their chillums or drinking slugs of asli ghee.

They come from a range of backgrounds. Some are rural youth whose families send them off to become Nagas for want of better employment.

Rent-a-Naga is a thriving business as many akharas want to show off their strength by the numbers of Nagas they can muster during the bath.

Some Nagas are educated professionals, who find themselves drawn to the life of the sadhu as a path towards individual fulfilment.

Please click NEXT to see more...

Baba Rampuri is an American who has been a sadhu for 43 years

Ashtkosal Raghunandan Bharti, a Naga, was once a BSc in chemistry from Benares University who decided to become a Naga to escape from the trap of domesticity his family had planned for him.

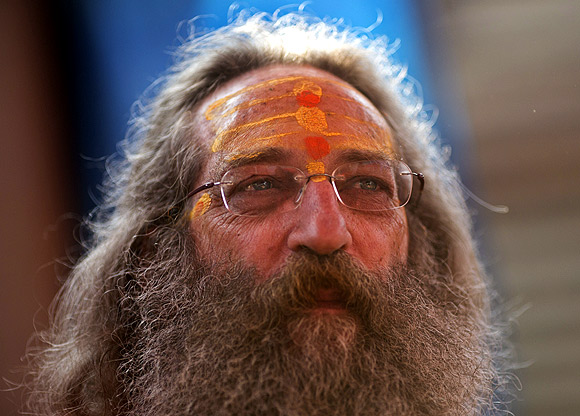

Baba Rampuri is an American who has been a sadhu with the Juna Akhara for 43 years, starting as a novice, to today when he has his own tent and his own followers. Baba Rampuri speaks fluent Hindi, has a long flowing beard and believes the Kumbh is the greatest celebration of Indian diversity.

The Australian historian, Kama Maclean in her book Power and Pilgrimage: The Allahabad Kumbh Mela writes that the Kumbh is not as ancient, or as Puranic as presumed to be, but is a post 1857 phenomenon, a festival created to escape British regulations, a less than 150-year-old event transposed on an older Magh Mela or bathing ritual which had traditionally taken place on the banks of the Ganga at Allahabad.

Whatever its exact origins, diversity, plurality, multiplicity are the defining features of the Mahakumbh; thousands of sects, religious orders, priests, Jain monks, Buddhist nuns, even a group of Christians, all are welcome.

On the banks of the Sangam stands the Allahabad Fort, Emperor Akbar's largest fort, which the creator of the Din-i-Ilahi or Sulh-i-kul built, as if to say, I too am here.

The Mahakumbh upholds the spirit of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, or the whole world is my family. Every religion is welcome; every god finds its place in the pantheon.

Please click NEXT to see more...

The pilgrim gives the Kumbh its unique peaceful character

Ideologies of intolerance would be hideously out of place in the Mahakumbh where tolerance and co-existence are constant features.

The Naga babas are fiercely opposed to intolerance and religious disharmony and say they will always oppose those who play politics in the name of dharma.

Almost 80 lakh (8 million) took a dip in the Sangam this Makar Sankranti and the crowds are expected to double for the Shahi Snan of Mauni Amavasya (February 10). A Harvard University study has emphasised how remarkable it is that such a huge crowd remains relatively conflict-free.

This is probably because at the heart of that massive crowd is the kalpvasi. Jostling on bridges, standing in a patient line for toilets, packed into boats to float towards the Sangam, the kalpvasi remains quiet and dignified and it is he who gives the Kumbh its unique peaceful character.

The stampedes and deaths that have occurred at Kumbh Melas -- 430 died in a Kumbh Mela in Haridwar in 1820 -- and moments of mad frenzy, are generally aberrations at a gathering where meditation, bathing twice or thrice a day and performing small pujas take place in an atmosphere of calm goodwill in the mellow winter sun of North India.

Please click NEXT to see more...

Brahmins and Dalits bathe in the same Sangam

The Mahakumbh is the Ganga's kingdom. There is complete spiritual egalitarianism here. Brahmins and Dalits bathe in the same Sangam.

Investment bankers and lawyers from the West take a dip alongside rustic pious folk from across India.

The pace of the river, slow, calm and majestic dictates the pace of life on the banks. The smells of incense, ghee, frying jalebis, agarbatti, sindoor and the ever-present cannabis waft in the air.

There are no big brands advertised at the Kumbh, it retains a rustic, rural and downmarket identity, even though luxurious tents and five star facilities for celebrities and famous ashram devotees are slowly becoming more prevalent.

The majority of people at the Mahakumbh are working and middle class, drawn not necessarily from India's metros.

The other large contingent is the Western yoga devotees and gurus for whom the Kumbh provides a source of solace in a way that their own religions do not.

Sadhvi Bhagwati of the Parmarth ashram is an American with a PhD from Stanford. She says the life of hectic modernity, with pills to sleep and pills to wake up, has ceased to provide happiness in the West. Walk into a shopping mall, she says, and try and see if you can actually find anyone smiling.

I visited the Kumbh as a journalist, but always find myself becoming somewhat of a pilgrim, drawn to the strange intoxication of the Sangam. The open-ness and tolerance of Sanatan Dharma in its true form, the myriad sects and ways to truth, the unassuming kalpvasi, ever-ready with a smile and words of help, the Mahakumbh to me has always evoked memories of what an older era of Hinduism must have been, its strength in its diversity and acceptance, its spirit resting not in priests but in individual bhakti, a faith totally alien to intolerance and bigotry.

Sagarika Ghose is Deputy Editor CNN-IBN. Her novel Blind Faith is based on her experiences at the Mahakumbh of 2001.