| « Back to article | Print this article |

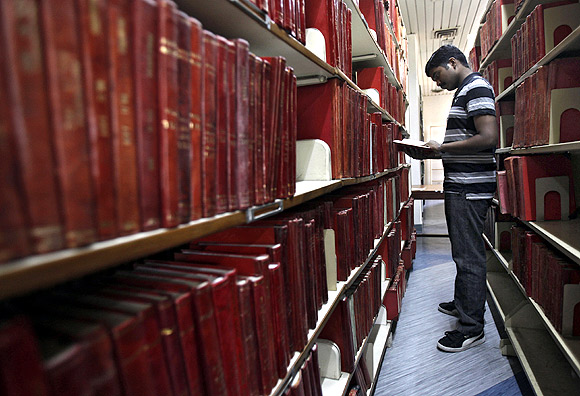

'Everyone wants to be English-speaking in India'

'English has become the most aspirational language for India's poor and disadvantaged. Anyone who has any desire to improve their prospects and wants upward mobility, the first thing they do is try to learn English.'

Writer Zareer Masani explains Thomas Macaulay's legacy in a fascinating interview with Rediff.com's Archana Masih.

'If you're an Indian reading this book in English, it's probably because of Macaulay,' says the blurb on the book cover of Macaulay, Pioneer of India's Modernisation by Zareer Masani.

Thomas Babington Macaulay, the British politician who introduced the English language as a medium for education, spent just four years in India, but has left behind a highly debated legacy. That is why even 178 years after English was introduced in Indian schools, he continues to be both admired and reviled in India.

Masani, who has an Oxford DPhil with a thesis on Indian nationalism, says that though largely forgotten in the land of his birth, Thomas Macaulay's legacies are alive and hotly contested in the Subcontinent -- and it is time for a balanced reprisal of his contribution.

The author of three other books on India and son of freedom fighter and politician Minoo Masani -- a member of the Constituent Assembly that drafted the Constitution -- Zareer Masani spends time between Mumbai and London.

In an engaging conversation with Rediff.com's Archana Masih , Masani explains why Thomas Macaulay still remains relevant and widely debated in India's history.

Many Indians don't see English as a foreign language, but as a language of their own, in that case won't we perhaps say that the Indians of today are more of Liberalisation's Children rather than Macaulay's Children? And that the relevance of the term 'Macaulay's Children' has receded in present-day India?

No, because liberalisation also stems from Macaulay's thinking.

If you go back to Macaulay's thinking in the 1840s, he saw English as a global language.

He also saw capitalism as a global phenomenon that would increasingly involve free trade across the world, globalised markets, people would need to communicate with each other much more across the world and English was going to be the vehicle for that.

Therefore, he advocated English for Indians because it was going to be the world language. He foresaw that.

In a way, it is part of the whole liberalisation process and you can say that the kind of policies we had in the 1940sm 1950s was an aberration from this kind of progression towards a free market, globalised economy which would involve India in a global market where English would be the language of communication.

So in a way we are back on track as it were.

What do you see Macaulay's legacy today -- barring in the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata, I don't think he has any portrait or plaque in India?

We are seeing it very dramatically in the way English has become the most aspirational language for India's poor and disadvantaged. Anyone who has any desire to improve their prospects and wants upward mobility, the first thing they do is try to learn English.

Even in rural India there is a great demand for English medium schools, even though the English they are taught is of a very poor standard which is a problem India needs to address.

The goal we are seeing is that everyone wants to be English-speaking (in India).

I think that is his legacy in a way that it is no longer seen as a preserve of the elite, English is expanding almost to the extent that Hindi is. The numbers are increasing quite dramatically year by year.

'There was never really a concept of India as a national entity'

In your book you say that Macaulay's institutional legacies are the glue that have held India together. Could you explain that?

The very concept of India, the word India is very Western, colonial concept. There was no concept of India before that.

There had been various kingdoms and rulers that had ruled parts of India, the majority of India, even the whole of India, but there was never really a concept of India as a national entity.

That was a colonial construct and with that came the whole language of the nation State at a time when Britain was the leading nation State in the world.

That was then taken on by Indian nationalists who were educated at Western universities about Western ideas of national sovereignty.

That concept took root out of Western education that there could be a nation State of India. That concept would not have existed otherwise.

Unlike China which had a concept of China that went back a couple of thousand years, there was never really a concept of India. The Mughal Empire was a collection of conquered territories ruled by a dynasty.

What about post-Independence, how have Macaulay's legacies made India stronger after 1947?

The Constitution is based on principles that really go back to the Whig enlightenment in England. The chapter on fundamental rights in the Indian Constitution is very closely based on the kinds of rights that Britain without having a written constitution had enshrined.

The main author on the chapter on fundamental rights was Dr Ambedkar who chaired the committee which my father was a member of that drafted the chapter on fundamental rights.

Ambedkar was a great admirer of Macaulay and his thinking. I think the Constitution is permeated by that, at least the fundamental rights section.

Then the whole federal part of the Constitution that you can have states that are autonomous and have their own languages and regional identities with a federal Centre.

Then, of course, English was retained as a link language of the central government.

So without English I don't see how the central government would have actually governed the higher civil service, the judiciary -- how else would the people in Assam be linked to Tamil Nadu through the same central government.

Though Hindi is claimed to be the official language of India, de facto really the effective lingua franca is English.

'Persian was linked with the supremacy of the Mughals'

It is said that within 30 years after English was introduced, Persian almost disappeared as the official language.

Persian was the court language. It was used as an official language. It was used for poetry and high flown literature at the princely courts.

It was not a language that most people spoke unless you were Mughal courtiers. In that sense it was quite easy to replace.

If you compare English today with Persian, though English is not the official language -- the state languages have become the official court languages -- but English is used widely in the economy, everyday lives, films, media. Persian was much more restricted.

The adoption of English marked the death of Persian, don't you think that the British could have kept it alive by giving it some sort of patronage as well?

Yes, they could have and there was a lobby, but the resources at that time were very limited. They were going to spend so much on Indian education, should it go to Persian, Sanskrit and Arabic or should it go to English?

And Macaulay's view which prevailed was it should go to English.

It could have gone to Persian, Sanskrit and Arabic, but I suppose if it had I don't know if Persian would have survived because it was linked with the supremacy of the Mughals.

India inevitably would have evolved into a Hindu majority and there would be much more Hindu nationalism which would probably emphasise Sanskrit and languages derived from Sanskrit, so I don't think Persian would have survived either way. By now, it would have died out anyway.

'In India there is a kind of Brahamanical legacy'

Macaulay's Children, (a term used for Indians who received an elite English education in India) were at least in the past, thought to be the Indian elite, removed from the reality of India.

Many of them joined the Indian bureaucracy and were thought to be disconnected with the masses that they governed. Do you agree?

I don't think it meant that you were cut off from the rest of India. The ICS (Indian Civil Service, the ancestor of the present-day Indian Administrative Service) officers spoke Hindustani, were interested and studied deeply anthropology and local customs more than the civil servants today.

When the civil services were Indianised which happened during the last 30, 40 years of the Raj and after Independence, they were bilingual and were fully able to communicate with the people in the districts they were administering. They were not at all cut off.

I am not referring to language, but more about their way of thinking, their mindset?

That is a class phenomenon. Whatever language you speak, you can be cut off by class. It doesn't mean you are any more in touch if you are a wealthy upper class Indian who speaks Hindi, but doesn't speak English.

I don't think that makes it any more sensitive to people at the bottom of the hierarchy. I don't think language cuts you off, elitism obviously has existed throughout.

When Macaulay came to India one of the things that most struck him was how completely cut off the elites were from the ordinary people.

That huge gap which was much bigger than anything in England at that time between the power of the rich and the poor -- in fact you had actual slavery in India and people could be literally owned by the nobility.

It was that kind of arbitrary power that the Indian elite had and I think that has been moderated by Western education. People have been made aware that they do have rights whether they are rich or poor, that concept of human rights came from Western literature.

It didn't exist in Indian thought because Indian thought from the time of the Upanishads and the Vedas emphasised on hierarchy.

The Brahmanical culture was that if you were part of the elite you were completely cut off, you would not even let the shadow of the people lower down fall on you.

In India there is a kind of Brahamanical legacy which I don't think is to do with Western education or English.

That is part of India's class and caste system which overlap.

'English has been an emanicipating language'

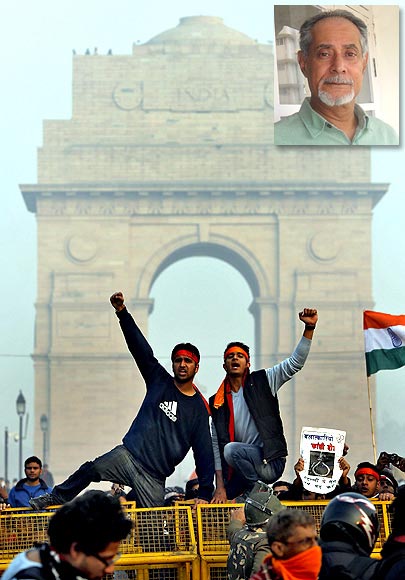

You talk of the gap between the rich and poor that existed at that time, but that gap still exists and one can say that the political elite is far removed from the people they govern?

Absolutely, but that is sort of entrenched in India's history and culture. We can't blame English education for that.

If anything, English has been an emanicipating language, even today the kind of challenges that are coming to an unaccountable corrupt government comes through empowering people through a global language of human rights, becoming part of global communities.

The Internet is playing a very important role making people aware of the struggles going on in other parts of the world for basic civil rights.

English again is a very important window on the world for India's disadvantaged communities I would argue.

You mention how the quality of English has deteriorated. When did the quality start suffering?

I think when the quantity started increasing. I don't think that the quality is any significantly worse than it was in elite schools.

In the 1950s when people like me were going to school, I think English was being very well taught as it had been during the colonial period in the convent schools which had very good English teachers.

At that time the British used to say upper caste educated Indians speak better English than their English counterparts.

At the top the standard has remained pretty high, where it has declined is in the newer schools that have sprung up and also in the former vernacular mediums which have introduced English because they have not put emphasis on good quality teachers.

Part II of this interesting interview: 'I don't think Rahul has a vision for India'