| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Al Faran's kidnappings were useful to expose Pakistan'

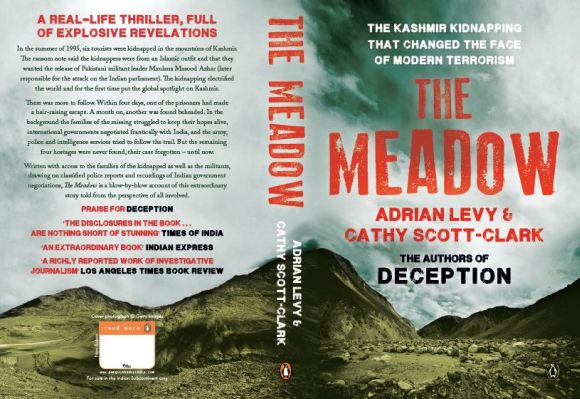

According to its descriptor on amazon.com, The Meadow, by Adrian Levy and Cathy Scott-Clark,is a 'shocking story of brutal kidnapping in Kashmir which marked the beginning of modern-day terrorism.

'In July 1995, 10 Western backpackers come to Kashmir in search of many things to take a trip of a lifetime. They have come in search of many things -- nirvana, exhilaration, a sense of self. But over the course of the next week, their holidays take a terrifying turn when they become entangled in a nail-biting hostage drama that will suck them into an alien world of jihad and Islamic fundamentalism. In the months that follow, their fates will become caught-up in a bloody struggle between India and Pakistan, fought out in the airless heights of Kashmir'.

In The Meadow Levy and Scott-Clark focus on the deadly Al Faran group which was responsible for the kidnappings of 1995, and also the reveal how the Indian government and the Army allowed the Western hostages to die, all as part of the larger political game.

In an interview with Vicky Nanjappa, award-winning author Levy, who has written three other investigative books, takes us through The Meadow.

The book deals with the manner in which the Indian government and the military allowed the hostages to die as part of a larger political game. What was the role played by the Indian government and when did you realise the same during your research?

The crux of the book is not that straight forward. First, Pakistan enabled an act of terror, which led to the abduction of six tourists in total, the barbaric beheading of one of them and the imprisonment of four others. The kidnappers' leadership was grown in Pakistan, funded and trained in Karachi, the Punjab and Muzaffarabad, before being infiltrated across the LoC, kidnapping tourists (as their initial targets -- foreign engineers -- had got away).

Indian intelligence recognised the crime from the off as an error on Pakistan's part. It was potentially a useful tool with which to expose its neighbour's proclivity for dabbling in Kashmir and making India bleed, at a time when the West was reticent to comment on Kashmir (and perceived the state's insurgency as a human rights issue).

'We were certain from the start that there would be a political dimension'

Rather than quickly solving the crime, as it had many others that came before it, a clique within intelligence and the Army made it run long so as to eke out maximum pain for Pakistan, fulfilling a key plank of the (former prime minister PV Narasimha) Rao doctrine, to frame Pakistan as a State sponsor of terror, winning an argument on the international stage where India had spectacularly failed before to get heard on terrorism and Pakistan.

In the end, when Al Faran had folded, exhausted, frozen and demoralised, State-sponsored renegades took over the hostages, to keep the crime running, men who had the support of a rogue element in the Valley's intel and military establishment.

These figures, led by Nabi Azad, had grown within a short time beyond control, and were as criminal as they were brutally effective. The same could be said of the J&K police's special task force or SoG, which worked with them.

We had no inkling of the ending when we began. We thought this was probably a dirty, opaque story and like many incidents in Kashmir, was likely to be complex, and fraught with difficulty. We thought too that this was an everyman tale, innocents packing their bags for a dream holiday that goes horribly wrong, people taking ordinary decisions, as we all do, that have unforeseen consequences. However, this being Kashmir, we were certain from the start that there would be a political dimension and indeed there was.

'Every stage of the talks was undermined by leaks'

How do you think India has gained or lost as a result of this incident? You have quoted (inspector general of police) Rajinder Tikoo as stating that there was a sabotage during the negotiations as the Indian Intelligence Bureau didn't want it.

The J&K police, the security advisor to the governor, and others tried to solve the crime, and nearly all concluded they were impeded by external forces. Every crucial stage of the secret talks between India and Al Faran was undermined by a pattern of leaks so persistent and accomplished, dealing in highly classified information, that it had to stem from a very high level. Politicians and civil servants reflecting on this period recall that they were sidelined by the military and intelligence factions that ran the show. This suggests and they believe that some in intelligence were behind the leaks -- rather than the odd drunk policeman as one reporter has lately suggested.

The feeling within the Al Faran inquiry itself was that it was being sabotaged from without. This view was widely held, and debated. And then hushed up. An inquiry into this episode might discover the names of the leakers and then grill them, on their intentions.

Prior to this, the IB and R&AW, as well as some in the Army, knew of the hostages' whereabouts for almost the entire time they were in the Warwan Valley -- some 10 or 11 weeks. The police discovered this by interviewing villagers there and sampling statements from a network of informers and agents they had in place. IB/Army acquired photos of the hostages so detailed that according to some of the agents who saw them they could see the sweat in their brow as they played ball games, to alleviate their boredom.

Villagers in the Warwan reported on numerous occasions the hostages' presence to the Rashtriya Rifles. On at least one occasion, documented by the police, villagers complained to they were beaten and detained by soldiers of the Victor Force who told them to mind their own business.

What India 'gained' from all of this was to create a visceral image of Kashmir in the West as a cradle of terrorism rather than a paradise Valley. However, as many senior police and intelligence officers conceded, what was lost in all of this war and gamesmanship was humanity.

'Some in Narasimha Rao's inner circle must have known something'

You have pointed out that Indian politicians had said the entire kidnapping incident was not in their control as there was governor's rule in the Valley. How true do you think this statement was?

I think there is a good deal of truth in this. The political setup had been quashed. The governor in J&K was in charge. He was surrounded by military and intelligence factions who presented an often distorted and conflicting view of the Valley. War creates distortion. But here intelligence fed the governor and then acted on their own intelligence too, without oversight of any kind.

Compare this to 1999, and the hijacking of Flight 814. In 1999 the politicians were in charge, and consulted Intelligence Bureau and Research and Analysis Wing, some agents advising them to sacrifice the passengers on the jet, as "that many people die every month in India".

However, the advice was over-ridden. Instead, watching the teary demonstrations outside the prime minister's house in Delhi build, and families threaten to immolate themselves, noisy families who never shut up, while the families in 1995 were told by all in power to say nothing and keep quiet, the government rolled, fearing the political price of not doing so, and ordered the release of Masood Azhar, as well as (Mushtaq) Latram (Zargar) and Omar Sheikh.

Senior contacts in the 'civil service' in Kashmir and Delhi were out of the loop. Some in Rao's inner circle must have known something.

Did you manage to get names of those in the political circles and also the Indian security establishment who were responsible? Who do you think from New Delhi in the PV Narasimha Rao government was controlling the situation?

An inquiry needs to establish this precise question. Who sabotaged Tikoo's negotiations? Who sabotaged the operation to free the hostages? An independent hearing that seeks out all those connected might resolve that question.

'Al Faran settled for Indian money, but this deal was exposed'

It is stated that India's agenda was to show that terrorism in Kashmir was backed by Pakistan. What is the thinking in Pakistan regarding this and what did you find during your various interviews conducted with those close to the Al Faran group?

There has been no official comment on the findings of the book in Pakistan yet, although there was concern at the time about the Al Faran case. Federal investigators and Benazir Bhutto in 1995 expressed dismay to us about the beheading of one of the hostages, Hans Christian Ostro, describing the killing as "a watershed". That kind of act was unknown before then, and yet afterwards it would become part of the grammar of the so-called terror war.

The impression we gained from police statements and eye-witness, as well as from mujahids in Pakistan, was that Al Faran or Harkat al Ansar, as it was, would have rolled over and released the hostages, but was prevented from doing so. However, the Al Faran team, former Harkat al Ansar people say, was divided, with one faction siding after a time with the hostages. Some in the party together with villagers from the Warwan seem also to have assisted the hostages with an escape bid and to get their messages out -- some of which, incredibly, eventually reached Srinagar.

However, there was also another, hardline faction within Al Faran, led by a foreign fighter known as The Turk, that was more pragmatic and battle-hardened. This faction was behind the decapitation of Ostro, something for which it was admonished by its handlers in Pakistan, who saw it as a senselessly cruel act that would play terribly in the Western press, which it did.

The Al Faran ultimately gave in, they say too. They settled for Indian money. This deal was exposed and sunk so as to prevent it happening. They then let it be known that they would offer the hostages up for free. At this stage renegades were instructed by their handlers to try and buy the hostages from Al Faran.

'At present youth in Kashmir are shunning the gun'

Looking at Kashmir today, what are your views on the militancy there and also what sort of a role are both India and Pakistan playing?

The Indian Army says that foreign militancy has dipped to about 125 fighters, with total militancy standing at 400-odd fighters. Is this a militancy at all? And yet, emergency legislation to counter a fully-fledged militancy remains in place, the AFSPA, the PSA etc, 'lawless laws', as Amnesty calls them, that prevent the judiciary operating freely and that undermine India's claim to establishing equanimity in the state. The militarisation of the Valley remains as well, a place where the security forces admit that not a single prosecution has succeeded against them since 1989, although approximately 59 court-martials have taken place against nameless soldiers, for unknown crimes. These issues remain live in the mind of the international community.

At present youth in Kashmir are shunning the gun. The figures show that as do our extensive interviews in the Valley. How long will this window of opportunity remain open, especially after the non starter of the interlocutors sent from Delhi? Already, a section of society in the Valley is visibly moving very rapidly towards radical forms of Islam, that are not organic to the Valley, which are offering 'respite' to alienated teenagers, and also moving them towards a kind of conservative, hard line religiosity never seen before in Kashmir and that could wreak havoc if no real normalcy prevails.

On the Pakistan side, there is far greater instability now than ever, with the military in a bruising conflict with its US sponsors, and the civilian government staggering from crisis to crisis, especially with the judiciary. A destabilised Pakistan is disastrous news for peace in Kashmir, and post-Mumbai there is little cause for cheer in Pakistan-India relations.

'Post the 2010 agitations, an opportunity presented itself'

Based on your experiences which country (India or Pakistan) would you fault for the state that Kashmir is in?

I don't want to get involved in a blame game. However, Britain evidently played a disastrous role at Partition. Pakistan repeatedly has used Kashmir as its default bargaining chip, a substitute for any progressive foreign policy. India has failed to act imaginatively or boldly in the Valley, other than its creative use of intelligence assets etc, throwing money and little else into the equation. Where are the big ideas to outflank the default positions of succession (to Pak) and Islamism?

Post the 2010 agitations, an opportunity presented itself but that too has been lost.

The information that has been put out in this book is shocking. Could you tell us a bit about the difficulties and pitfalls faced by you and Cathy-Scott while going about your work for this book?

We spent several years on this, dipping also into 18 years of prior work in the region that has aided us in developing really good contacts on both sides of the LoC. We travelled extensively across J&K, interviewing hundreds of eyewitnesses, former intelligence agents and their assets, police officers serving and retired, politicians and civil servants, renegades and their families, army officers (retired), jihadis in Pakistan, former militants in Kashmir, intelligence and investigative agents and officers in Islamabad, Karachi, Lahore and Peshawar, as well as their opposite numbers in Delhi, Jammu and Srinagar.

Some of the work was done while we were carrying out other reporting duties.

We have been working in Kashmir as writers and foreign correspondents, for The Sunday Times and then the Guardian, since the era of the kidnappings, following events unfold in J&K and across the subcontinent.

We reported and investigated Pakistan's intervention in Kashmir, its backing of the armed struggle and its subtler steering of the political scene, too. We heard it from Indian intelligence agents and saw for ourselves in Pakistan that jihadeers were getting up steam to stoke Kashmir.

'J&K became a proving ground for the intelligence agencies on both sides'

We also reported in detail India's response, and how in this state of constant emergencies the law (and often moral judgements) was subverted to satisfy the supposed security demands of two countries fighting a proxy war. The same had been true in our protracted non-war in Northern Ireland, where we subsequently discovered that our security services had lost their moral compass, on many occasions, so desperate had our government been to win.

Some of this research went into our book Deception: Pakistan, the United States and the Secret Trade in Nuclear Weapons of 2007, which charted how the US had secretly abetted the Pakistan nuclear programme, creating a volatile regional landscape that today we are still learning to deal with. We recounted how George Bush's "axis of evil" was partially enabled by the US itself that had had a lot to do also with unravelling the epoch of terror we are still living in now.

We covered massacres and cold-blooded killings in J&K perpetrated by militants, Kashmiri jihadis, foreign fighters, and Indian soldiers and spies. We witnessed Pakistan's adventurism in the Kargil heights, but we also gradually saw how all sides lost their humanity in the melee that no one was winning.

The lack of oversight and accountability, through the judicial and parliamentary systems, which were often held in abeyance, led to massive abuses of power in J&K: rapes, murders, abductions, torture, disappearances. And seldom was a guilty party prosecuted or put on trial. J&K became a kind of proving ground for the intelligence agencies on both sides of the Line of Control, a place from where they have been reticent to leave.

While in the West, torture, renditions, political judgement and human rights abuses are now seized upon and rigorously investigated, igniting massive debates as to what defines our humanity, nothing of the sort has happened in Kashmir or elsewhere in India where the non-war (that has in recent years all but been extinguished in J&K) has been poorly reported and analysed, its real cost still unknown, any debate about its continuance framed by allegations of treason and heresy.

That changed somewhat after 2005 when the earthquake opened up vast areas of the Valley. Out of the disaster, which enabled lawyers and reporters to travel freely everywhere, rose the first accounts of unmarked and mass graves. An open discussion about the disappeared in Kashmir took flight too. By 2008, it became clear that the two issues were likely inter-related, leading to the first credible reports on the missing and the unlawfully buried, the scale of which gave some clue as to the full horrors of what had taken place in this non-war. How much had Pakistan thrown into the Valley to set it on fire? How far had India gone to quell the insurgency and rebuff its neighbour? How badly had the residents of the state suffered, caught in the firing line? The price appeared unconscionable on all sides.

'Numbers were not the story in the kidnappings'

People also started to talk about Kashmir's most puzzling missing case: the Al Faran episode. New eye-witnesses, old hands who had investigated it. A sea-change also took place within the Indian establishment where former and serving police and agents began to open up, as if they too felt that enough was enough. For some the Al Faran case represented justice delayed, for others, justice denied, and for another faction it was a myth that needed to be dispelled. People we tracked down were relieved to talk and said they had been sitting guiltily on secrets for 16 years.

Only six people were directly affected in this case, and many tens of thousands of souls have been victims of the Kashmir crisis. Why pay undue attention to these six only? We were asked this over and over as we began investigating. But we sensed that the numbers were not the story and that through this one small case of six trekkers who were abducted, a reader could see much of the entire Kashmir imbroglio. This one seemingly insignificant crime, when compared to the daily tragedies of Valley life, was a prism through which to assay the cost of the war.

Do you feel these revelations of the manner in which the Indian establishment reacted to the kidnappings would strain India's relations with the US, the UK or Germany?

I don't think it will do on an official level, as trade comes before everything. However, I do think it has revealed something of the truth about the Kashmir imbroglio, the cost to all sides, India and Pakistan, and what has been done in the name of winning.

How has your book been received overseas?

The book has caused consternation and some pain in the United Kingdom and the United States as it delves into matters that are still raw and touches on a wider relationship (between the UK and India) that remains tense, in a familial sense.

The book is not yet out in India and so we await a response which I am certain will be as divided as is public and institutional opinion on Kashmir generally.

However, the book is far more nuanced than some people evidently imagine, and contains a subtler and more balanced analysis than some people are giving us credit for.

For example, the director general of police in Srinagar, (Kuldeep) Khoda, described it recently as "rubbish". Given that he has not read it, nor studied the evidence, or been involved in the initial inquiry, I think it would be fair to say that this constitutes an uniformed response.Top photo features of the week

Click on MORE to see another set of PHOTO features...