| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Sisters and Brothers of America '

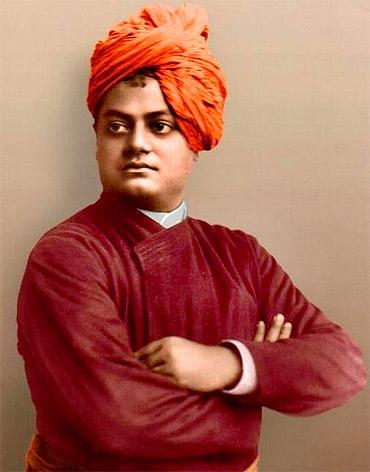

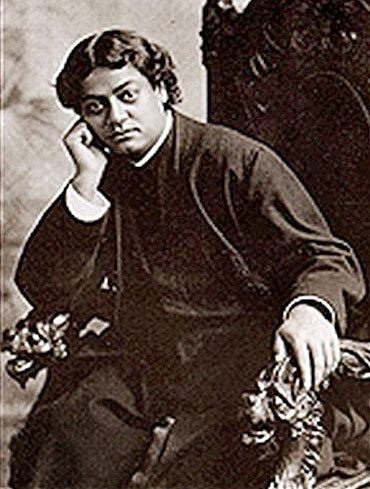

Swami Vivekananda's famous speech in Chicago at the Parliament of Religions played a key role in spreading Hindu philosophy in the West.

On Swami Vivekananda's 149th birth anniversary, Shashi Shekhar reconstructs the Indian spiritual leader's nearly decade-long stay in the US from a collage of original newspaper clippings that give a first-hand account of impressions of his life and teachings while in America.

A decade back on a first visit to the American City of Chicago, I was overcome by a desire to visit the hall where Swami Vivekananda had made his famous speech almost a century before.

Back then the Internet was not quite the powerhouse of information that it is today. There was very little information to go by to track down where exactly that speech was delivered and if there was any memorial at all of the events from that last decade of that Century.

More recently Swami Vivekananda's visit to the United States was brought forth to the mind while listening to a speech by Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi who sought to give a new meaning to the date September 11 marking the day when Swami Vivekananda delivered that famous speech in Chicago.

Thus began a digital quest to reconstruct the events of the 1890s during Swami Vivekananda's visit and stay in the United States. Thanks to the digital news archives of The New York Times and the Chicago Tribune among others we are able to today assemble a collage of original newspaper clippings from that decade that give a firsthand account of impressions if not insights to that visit and stay spanning nearly a decade.

The Chicago Tribune naturally has the most number of news items of the Swami's visit to the US while The New York Times gives some glimpses of his stay in the New York area. One also gains a peek into events that perhaps few are familiar with in the years leading up to the Swami's passing away and its immediate aftermath.

Most of the newspaper clippings are from the year 1893 when the Parliament of Religions was held in Chicago. In a curtain raiser that appeared in the Chicago Tribune dated September 11, 1893 with the title 'Study of Comparative Religions' one gets a perspective from a local Presbyterian Church on what to expect from the Parliament.

Please click on Next to read further.

Swami Vivekanand emphasised tolerance and rejected bigotry

It was interesting to note how the local clergy viewed the event as being no threat to Christianity, but an opportunity to witness, as the report put it, 'the grandest successes and the most pathetic failures in the highest plane of human endeavor.'

In a series of articles that appeared on September 12, 1893 one gets a detailed glimpse of the launch of the Parliament. In a report titled 'The Opening of the Great Parliament', the Chicago Tribune lists all of the major participants in the Parliament.

It may be a common misconception that Swami Vivekananda was the only Hindu in attendance when in fact there were many Indians.

Siddhu Ram from Punjab, Raghavji Gandhi, Reverend B B Nagarkar, P C Mazoomdar, Jinda Ram, Dharmapala, Professor G N Chakravarti were among others listed by the Chicago Tribune as being in attendance.

In fact P C Mazoomdar is quoted as one of the first speakers from India extending gratitude for the invitation to the Parliament, followed by Dharmapala speaking on behalf of the Buddhist community in India.

The report listed Swami Vivekananda being introduced in the afternoon session after a lunch recess. Another news report on the same day titled 'In a Common Cause' that appeared in the Chicago Tribune described Swami Viveknanda's attire that day as a 'single violent orange garment.'

The highlight of Swami Vivekananda's opening remarks reported by the Chicago Tribune was his emphasis on tolerance. In fact Swami Vivekananda's rejection of bigotry needs to be reproduced in full for the benefit of many who swear by him in the present times to introspect and reflect:

'...Sectarianism, bigotry and its horrible descendant fanaticism have filled the earth with violence, drenched it often and often with human gore, destroyed civilisation and sent whole nations into despair. Had it not been for this horrible demon, society would have been much farther advanced than it is today ... this parliament that is assembled is the death knell to all fanaticism, death knell to all persecution with the sword or the pen and to all uncharitable feelings between brethren wending their way to the same goal but through different ways...'

Please click on Next to read further.

Swami Vivekananda debunked spirituality and vegetarianism

The next extensive reportage on Swami Vivekananda comes nine days later from the Chicago Tribune on September 20, 1893.

The report titled 'Hindoo criticizes Christianity' carries extensive excerpts from Swamiji's speech under the sub-section titled 'Christianity is Intolerant'.

The report quotes Vivekananda saying '...I have sat here today and I have heard the height of intolerance... Blood and sword are not for the Hindu who's religion is based on the law of love...' The report then goes on to carry an extended discourse from the Swamiji on Vedanta with these closing remarks that are significant even today.

'...The Hindoo religion does not consist in struggles and attempts to believe a certain doctrine or dogma, but in the realizing not in the believing, but in the being and becoming. The whole struggle in their system is a constant struggle to become perfect... this becoming perfect... constitutes the religion of the Hindoos...'

In a report titled 'Colored Methodists in Session' that appeared in the Chicago Tribune on September 23, the attendance to Swami Vivekananda's speech and the response of the audience was described as:

'...Hall3 was crowded to overflowing and hundreds of questions were asked by auditors and answered by the great Sanyasi with wonderful skill and lucidity. At the close of the session he was met by eager questioners who begged him to give a semi-public lecture somewhere on the subject of his religion..'

One reads of Swami Vivekananda's travels in the United States on and off over the next few years in assorted news clippings that appear in The New York Times listing social events at private residences and public lectures.

Of particular curiosity was an event in New York City in May of 1894 when Swamiji spoke on vegetarianism to an audience of fifty where he debunked the idea of spirituality and vegetarianism:

'...Some of the greatest propagandists of vegetarianism do not believe in God or in the existence of the soul...'

Please click on Next to read further.

One hopes there is renewed interest in his teachings as we near his 150th birth anniversary

In February of 1895 we learn from The New York Times of regular Sunday evening addresses by Swamiji in the Brooklyn area near New York City. The same story also reports that interest in his lectures increased into a demand for additional sessions.

We also learn of the existence of a formal entity titled 'Swami Vivekananda Educational Work.' In March of 1896 The New York Times interviews an American disciple of Vivekananda who was ordained into asceticism.

In April of the same year The New York Times carries a short review of a new publication on Vedanta by Swamji.

In May of 1897 a lengthy letter to the column appears in The New York Times by a Charles Higgins of the 'Brookly Ethical Association' that critiques common misconceptions around Swami Vivekananda in response to a piece by a Mr Blauss, correspondent of The New York Times, that among other things described the Swamiji as a 'Philosophical Quack.'

In November of 1899 The New York Times reports on the Swamiji's third visit to New York and a lecture in New York City followed by a lengthy book review of Swamiji's latest book of Vedanta in July of 1902 soon after which Swamiji passed away.

It is only four long years after his death, in January of 1906 that we see a strange story appear in The New York Times of the unfinished legal matter of the late Swami's will.

On January 17, 1906 The New York Times in a report that is wrongly titled 'Buddhist's Old Will' narrates the story of how for three long years lawyers struggled with how to dispose Swami Vivekananda's will.

The will, the report said, had been executed by the Swami on July 6, 1900 during a visit to the United States. The will talked of dividing his estate among five of his disciples.

The story goes into quite some detail on how for two years the executors in the United States attempted to communicate with the executors in India including reproducing a letter from Sister Nivedita.

The story concludes with a glimpse of the complexities encountered by an early 20th century American legal system in dealing with the will of a Hindu Swami who had renounced kith and kin.

As we near Swami Vivekananda's 150th birth anniversary in 2013 one hopes there is renewed interest in his life and teachings. This digital quest to discover firsthand accounts from a period his life that saw him receive global fame and attention is a small step towards rekindling that interest.

Shashi Shekhar is a social media commentator on Indian politics and public policy. His blog can be found at http://blog.offstumped.in