| « Back to article | Print this article |

It took the deaths of 23 children for change to come to this village

Archana Masih in Dharmasati Gandaman, Bihar

Five months after 23 children died from eating poison-laced school lunch, the tragedy has resulted in the construction of a new school, a creche, a health centre, roads and drainage system.

The long forgotten village is finally being turned into a model village, but the grief of its loss is far from over.

Green grass covers the grave where Vinod Mahato's child lies buried. The grave is a mound outside a small structure that once was a school.

Another grave lies a few metres away, right in front of the school. Ahead by the pond, more graves lie in a quiet cluster across the brick lined village road.

'On this road, on that day, children were staggering and vomiting. It was as if they were drunk. They were holding their stomachs and were crouching in pain," recalls an old woman in Bhojpuri, the local dialect.

The children had just eaten the school-provided midday meal of soyabean nuggets and rice. The deadly meal contaminated by pesticide took the lives of 23 children in the small village of Dharmasati Gandaman in Bihar's Saran district five months ago.

The incident shocked the country, showing the criminal neglect that permeates the government's school programme in some places.

India has the largest food programme serving 114 million children. It ranks 12th among 35 lower-middle-income countries covering 79 per cent of its total number of school-going children, according to the World Food Project.

Bihar provides the meal to 10 million children in 70, 238 schools everyday.

"I was passing by the school before lunch and saw that the children from my home were punished outside. I brought them home instead. Seeing them leave, some other kids who were also punished came along. By doing so they missed that deadly meal and lived," remembers the woman, who like that day, is passing by the school, where repairs are now on.

Kindly click Next to read further...

The enormous pain of losing 3 children in a day

It has taken a monumental tragedy such as this for change to finally come to this village. A new school building is being constructed, also an anganwadi (creche), a primary health centre, two roads and a canal.

Transformers for electricity have been installed and villagers say three of the transformers have started working.

The road leading to the village, local residents add, was built in record time once news of the tragedy brought the media and government officials to this unknown village. The Indira Awaas Yojana, a housing scheme for those living below the poverty line, has also been promised.

"This village is now being developed as a model village, but it has come at a great cost to us," says Akhilanand Mishra, who lost his five-year-old son in the tragedy.

Ashish Kumar, 5, had just taken a bite and on finding the food bitter had spat it out. "But that was enough to take his life," says his father, "He died on the way to the health centre in Mashrak," 10 to 12 kilometres away.

A wall bearing several plaques with information about upcoming government initiatives stands at the entrance to the village.

Chief Minister Nitish Kumar did not visit the village after the tragedy because of a reported foot injury. The villagers hope he will come when the new structures are inaugurated.

Vinod Mahato stands quietly among the crowd near the school. A labourer in his late 20s, he works on the site where the health centre is coming up.

From his work site he can see the grave where his son lies in final rest. The grave is like a sacred shrine to him. Whenever he stands beside it, he takes off his chappals, making sure his bare feet don't touch the edges.

Mahato's loss is enormous, he lost three children that day.

Arti, 9.

Shanti, 7

Vikas, 5

Kindly click Next to read further...

'I keep seeing their faces'

Like many of his fellow villagers Vinod Mahato worked as migrant labour in Ludhiana. A phone call from someone in his family informed him about the tragedy.

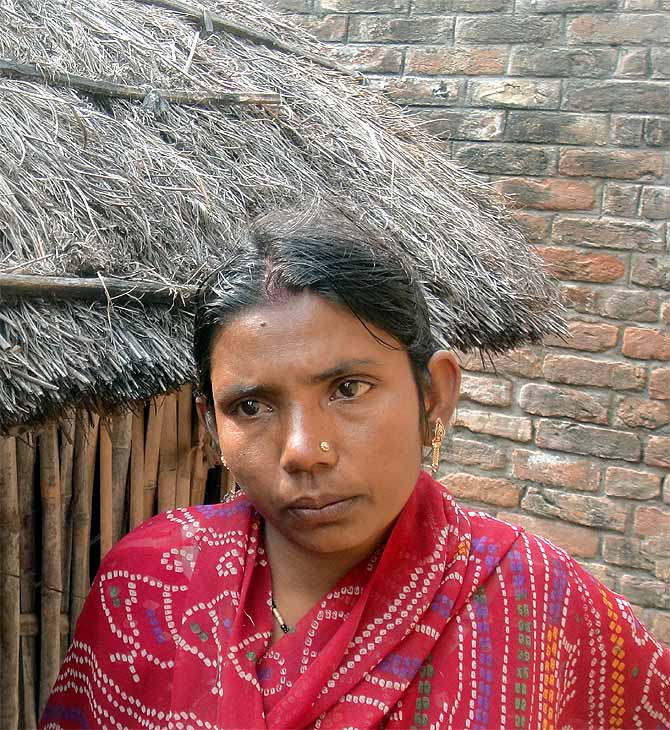

His wife Bucchi Devi, 25, carried one of the children in her arms till the main road until she found a vehicle to take them to hospital.

Vinod boarded a train the moment he heard the news. No sooner had he started the journey, he heard his son had breathed his last.

His daughter died a few minutes after reaching Patna, the state capital.

Time was lost in transporting the children to the district hospital in Chhapra, 55 km away and then to Patna, another 75 km ahead, because both the health centre in Mashrakh and the hospital in Chhapra were ill-equipped and unable to treat the lethal toxic.

Sixteen children died in Chhapra. Four died en route to Patna. Three died in Patna, highlighting the poor access to health care in India's villages.

Nine hours after reaching Patna, Vinod Mahato's other daughter also died.

That morning, his wife had sent the three children to school. The next morning, they were all dead.

After a three day train journey, when Vinod reached the village, his children had already been buried.

He did not get to see them.

Bucchi Devi carries their surviving two-year-old child in her arms. Her eyes are glazed; sadness seems to consume her entire being.

She stands outside her hut, with a small door that needs one to bend waist-down to enter.

"Since I lost my children, I can't sleep at night. My head always remains heavy and my heart feels as if it is racing. I keep seeing their faces," she says, tears running down her cheeks.

A relative says Bucchi Devi hardly eats and had to be taken to a doctor for saline drips two days ago. "She has become so weak," says her sister-in-law, "Grief has transformed her into someone else."

Kindly click Next to read further...

Many children have not resumed school

Five months after the tragedy, several children who survived the killer meal whom Rediff.com, met have not resumed school.

Only 14 have enrolled in the middle school, where a midday meal of khichdi with palak and mashed potatoes is being cooked by two lady cooks who are paid Rs 1,000 a month.

To keep away from any kind of contamination in storage like in the Gandaman case where toxic insecticide was found in the cooking oil, the headmaster says he buys the daily food requirement from the village bazaar.

Many of the classrooms do not have desks and chairs though new classrooms are being constructed on the premises. Except a couple of children, the children are not in uniform.

Parents of the children who survived the midday meal in Dharmasati Gandaman say their children are still scared to go to school. "We will send them once the new school building comes up," says a parent.

Some say the middle school has refused to admit the children, an accusation the headmaster denies, showing the register with the names of only the few that turned up. A resident adds that the quality of education is so poor in the government school that some villagers are forced to send their wards to a private school.

Kindly click Next to read further...

The school that wasn't

As they play around their huts, the children say they miss the classmates they lost that day in school.

But what they call a school could hardly be called one.

It was a one room community centre that functioned as a school. It accommodated children from Classes I to V, with two teachers (one was on maternity leave) and two cooks who prepared meals in the verandah.

Bihar returned approximately Rs 500 crore (Rs 5 billion) sanctioned by the Centre for construction of kitchen-sheds and storage facilities the previous financial year. It had spent only 50 to 60 percent of the money sanctioned for mid-day meals, Apoorvanand wrote on Rediff.com shortly after the tragedy.

The tragedy has initiated compulsory tasting of food before serving it to the children and a dedicated midday meal in-charge at the block level. Guidelines that already existed, but as the tragedy revealed were not followed.

Two months ago, the Press Trust of India reported that Bihar Education Minister P K Sahi had suggested a review of the cost of the midday meal scheme, saying that funding was grossly inadequate to ensure quality food.

Sahi said it was not possible to provide midday meals where the per unit cost comes to just about Rs 3.60. His suggestions were supported by education ministers from Chhattisgarh and Uttarakhand.

The expenditure of the midday meal is shared by the Centre and the state 75:25.

Bihar has allocated 23 per cent of the state budget to education. It is the highest sum set aside for education by any state in the country, a senior official in the chief minister's secretariat told Rediff.com

In spite of that, the state has to drastically improve school infrastructure and move beyond proclamations to ensure that education policies are implemented properly.

By not doing so, it fails its children every day.

Kindly click Next to read further...

'I will not leave the family... whatever remaining family I have'

The state government offered parents a compensation of Rs 200,000 for every dead child. Vinod Mahato received Rs 600,000 for his three children and has put away Rs 500,000 in a fixed deposit.

Mahato decided not to return to Ludhiana to earn a living and now works for Rs 200 a day on the construction site of the primary health centre.

"I will not leave the family... whatever remaining family I have," he says.

Meena Devi, the headmistress and the lone teacher at the school, has been charged with murder and is in jail. Her home is locked and neighbours say they don't know where her children now live.

Her husband Arjun Rai was also chargesheeted for buying the pesticide that got mixed with the midday meal.

The block education officer was removed. No other heads rolled.

A charred jeep belonging to the circle officer that was burnt by angry villagers in response to the tragedy lies by the road near the home.

Meanwhile, Dharmasati -- named after women who committed sati by committing themselves to the funeral pyre of their husbands -- still mourns its loss.

This year, many homes did not celebrate Diwali and Chhat, Bihar's most important festival.

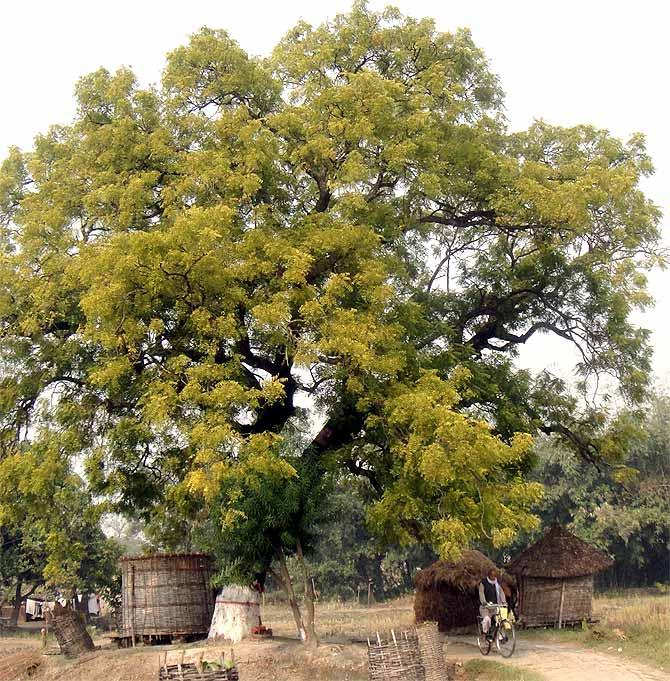

The village with around 400 families is quiet surrounded by green fields. Small pyramids or sun temples dedicated to Chhat Puja dot the entrance, where the new school, creche and health centre are being built. Villagers pass the wall bearing the names of all the new projects ever yday.

As bricks are offloaded and men put brick upon brick, Dharmasati's villagers hope that the children's tragic deaths have bequeathed a better village for the living.