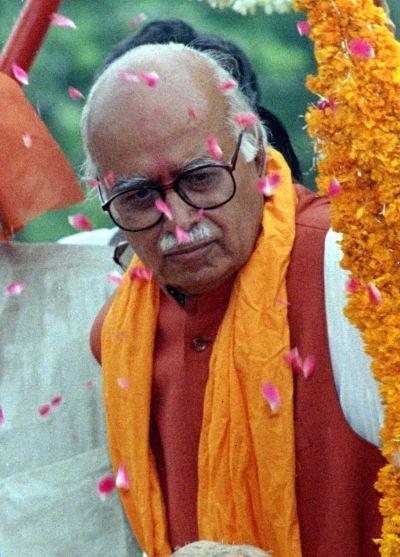

Photographs: Kamal Kishore/Reuters Aditi Phadnis

The BJP was leveraging Hindu religious leaders who'd banded under the Vishwa Hindu Parishad for building a Ram temple at the site of a masjid, notes Aditi Phadnis.

L K Advani's place in modern Indian political history is secure on the strength of his having presided over the biggest Hindu consolidation the country has seen. Like it or not, it happened.

He led the Ram Janmabhoomi campaign that led to the destruction of the Babri Masjid in the early 1990s, declaring at the same time when this happened that "it was the saddest day" in his life because party workers had run amok.

Later, he had no word of regret when Muslims in Gujarat were butchered in a pogrom in 2002, whereas Atal Bihari Vajpayee at least made some placatory noises (like asking the state government to do its duty).

That is why he is seen as a divisive figure, though Advani insists he is no bigot. He rarely goes to temples or wears external signs of being a Hindu. Indeed, people who meet him say they see a thoughtful and well-read individual, even a liberal, looking for ideas and for people to give them shape through action.

Edited excerpts from Political Profiles Of Cabals & Kings

Please ...

The organic link between BJP and RSS

Image: Advani addressing a campaign rally in BhopalPhotographs: Raj Patidar/Reuters

His is a long journey that began in Karachi where he began his career by joining the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh when still in his early teens. After Partition, he worked for some years in Rajasthan before moving to Delhi city politics and being asked by the Sangh to help the new-born Bharatiya Jana Sangh (as the BJP was known before 1979) to get moving.

He was the organic link between the BJP and its parent, the RSS, and has been more of a builder of the party than Vajpayee, familiar as he was with party workers at the local level in many parts.

In many ways, this was the pre-1989 Advani, a complete organisation man. This was a period of consolidation of the Hindu 'feeling' and for his energy and endeavour, even his worst enemies in the party will give Advani nine marks out of 10.

In 1986/87, Advani became president of the BJP for the first time. The party declared Hindutva (Hindu-ness) as its central credo. In 1989, the party entered into an electoral coalition with the Vishvanath Pratap Singh-led Janata Dal, having set up candidates strategically.

By now, Hindu nationalism had acquired definite brush strokes. The BJP was arguing that this was reflected in popular support to it -- its seats went up from two in 1984 to 86 in 1989, prompting scholars to ask if there was a Hindu vote in the making in India.

The BJP was leveraging Hindu religious leaders who'd banded under the Vishva Hindu Parishad for building a Ram temple at the site of a masjid, while being part of the support for the V P Singh government.

Please ...

'Moderate' Vajpayee and 'hardline' Advani

Photographs: Reuters

The focus was on Advani -- Vajpayee had withdrawn. Between 1989 and 1990, Advani had come into his own. As Vajpayee pretty much sat and sulked, it was Advani's time to seek his place in the sun.

The moment came in October 1990, when then chief minister of Bihar, Lalu Prasad Yadav, had Advani arrested there on charges of spreading communal hatred.

In the 1991 general election, although the BJP was unable to form a government, it became the principal opposition in the Lok Sabha. By now, Vajpayee was quite marginalised; there was already talk that Vajpayee was the 'moderate' face of the BJP, while Advani represented the 'hardliners'.

Advani did not bother to deny this, for it sent up his stock with the parent organisation, the RSS.

Between 1989 and 1996, there was another Advani in evidence. The man who had been 'spiritual' rather than 'religious' for most of his life, was now an aggressive, unapologetic Hindu -- but personally likeable and very much a team man. Each member of the team brought a little to the table in terms of making friends. The seeds for the concept of the National Democratic Alliance were laid around this time.

Decisions were taken by consensus; there was no such animal as an 'Advani man'.

As a result of the dynamic he had set in motion, Advani made a whole lot of new friends. These were men and women who saw a future for themselves in politics through the Hindu radicalisation route. They were professionals, those who fancied a role in public life and were dissatisfied with the Congress regency but might not have been Hindu-minded.

It is not that he forgot the tried and tested Sangh -- but the demands of mobilising a broader based movement were such that it devoured fresh political talent.

Please ...

The difficult years

Image: Advani with his family campaigning in Kanyakumari in 2004Photographs: Kamal Kishore/Reuters

But catastrophe followed. In the late 1990s, his name figured in the diaries of a little known businessman, listing political payoffs, some of them in violation of foreign exchange laws.

Advani was alleged to have received Rs 35 lakh from the businessman between April 1988 and March 1990. The government referred the case to the Central Bureau of Investigation. Advani declared that he would not contest another election till his name was cleared.

An editor with strongly anti-BJP leanings wrote in his column at the time: "If L K Advani is corrupt, I'm a banana".

The charge was scarcely believable. But it hurt Advani deeply. After all these years, was he going to have to stand up in court to proclaim his integrity? But what was even more upsetting was those very individuals who had seen him as India's great rising Hindu hope now ran shy of being seen with him. The party did not come to his defence.

That event added another layer to Advani's friendships. If earlier, his new friends were Hindu radical professionals, now he needed advisors who had not the party's, not Hinduism's, not Ayodhya's, but Lal Krishna Advani's personal and political interests at heart. They became friends in need.

Though he was exonerated in the case, its effects lingered. Over a period of time, decision-making within the BJP had become democratic out of necessity. But this system came to be supplanted by groups of those who supposedly had Advani's ear, post-Hawala.

They said and did what they thought Advani wanted. Everything else was secondary. So, past presidents like Murli Manohar Joshi were cut to size publicly. Not because it was good for the party but because they thought that's what Advani would want. The BJP never really understood how power passed from the party to consultants.

Please ...

The disconnect grew deeper

Image: Advani with Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and other NDA partners in 1999Photographs: Reuters

To cite an example: Ahead of the 2004 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP's relationship with the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (a natural ally in view of its anti-Congressism) in Tamil Nadu unravelled principally because of constant sniping between the party's local unit and the DMK.

Lulled by seemingly pro-Hindu moves made by rival Jayalalithaa, the Tamil Nadu unit of the BJP kept rubbishing the DMK. The personal affection between Karunanidhi and Vajapayee alone kept the relationship going as long as it did.

No one in the party sought a debate on what the TN unit of the party was doing, neither asking nor pulling it up. Angered, the DMK pulled out of the NDA. The BJP paid a heavy price for doing away with internal debate. If it had stayed with the DMK, it might have been able to form a government.

The core of the BJP thus weakened and the periphery became stronger. When Advani responded to the demands of the periphery, the RSS attacked him, instead of recognising that he was doing/saying what he was to keep the movement together, at the cost of weakening the Hindutva family.

The disconnect grew deeper as the BJP came to power at the Centre in 1996 (thirteen days) and 1998 (13 months). It then came to power with 300-plus seats in 1999. This should have been Advani's finest hour. He was appointed home minister and treated as the indisputable number 2.

Please ...

A record less than stellar

Image: Former Home Minister L K Advani inspecting the site of a bomb blast in Mumbai in 2003Photographs: Sherwin Crasto/Reuters

Maybe his judgment was coloured by the extreme loneliness of being out of the circle of power just a few years earlier. Maybe it was on advice of family -- the only circle of strength and protection around Advani in those testing months.

From 1999 to May 2004, he played number two to Vajpayee but his advisors stood with him to a man. There was much talk during this period, possibly because both leaders had their own 'advisors' that there was to be a split in the BJP. The Cassandras were proved wrong.

There were plenty of points of friction, however. The central one being the appointment of Vajpayee's friend and advisor, Brajesh Mishra, as the principal secretary to the prime minister and National Security Advisor.

Mishra was quick to point out that it was the prime minister he was principal secretary to, not the government. Advani and his advisors did everything possible to dislodge Mishra from his post but to no avail.

But what did happen was, as home minister, Advani began to drift away from the Sangh and the VHP. They thought now that they had the government, the Ram Temple was in their grasp. Instead they found Advani casual, even dismissive, about the Ram temple project.

As home minister his record was less than stellar -- although he saw himself as a second Sardar Patel, an uncompromising leader and India's first home minister. When Advani stepped down after six years in the home ministry, as many as 160 districts in the country had some or the other Maoist challenge building up. Clearly, he had failed to nip the problem in the bud.

Please ...

The biggest surprise

Image: Advani visits Pakistan's Grand Faisal Mosque in Islamabad during his 2005 trip to that countryPhotographs: Mian Khursheed/Reuters

The biggest surprise of his long career, came with his laudatory remarks about Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan.

Advani was on a visit there, in 2005. All he did was to pay tribute to a man who had built Pakistan singlehandedly. All the RSS saw was how Advani had been 'brainwashed' by his new friends. The irony was, many of these new friends, themselves overzealous new converts to the BJP cause, were the first to turn on Advani with ferocious fury and charge he had sold out.

The BJP was confused. On Jinnah, were they to listen to Advani, or to the RSS? More fundamental questions were raised. Was the BJP to continue to subserve the function it was founded for -- politics? Or was it to stand aside and let the RSS abandon its traditional role of social service as the way to create a Hindu constituency, supplanting the BJP's autonomy in political decision-making?

There was a suggestion that Advani was going soft in his old age. More sinister motives were imputed to him: that he was deliberately trying to improve his image and make it acceptable to a broader mass of people. Advani himself believes that he merely spoke the self–evident truth.

The fact is, the Jinnah episode was merely a cumulation of the distance that had grown between Advani and the Sangh. He felt the Sangh should have stood by him during the days of the CBI probe. The Sangh believed he should not have been as cavalier with them as he was when the BJP was in power.

Please ...

The tension continues

Image: Advani with Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi during a campaign rally in Gandhinagar.Photographs: Amit Dave/Reuters

Whatever the reason, Advani found he had few friends willing to stand by him and the RSS was clearly upset with him. He had to offer his resignation from the presidentship in 2005 and then slowly work his way back to the centre of things, finally being named the party's prime ministerial candidate in the 2009 elections.

Even then, many in the BJP felt naming him as PM at the age of 82 was a tactical error. Even then, there was opinion in favour of Narendra Modi instead.

One key to Advani then and now is that he remembers the unexpected defeat of 2004 and the need to get the party to focus on winning enough allies to form a coalition that can control more than half the seats in the Lok Sabha.

Though, after 2005, the Sangh and he kissed and made up later, the whole episode left the BJP shaken. The Sangh's explanation is too many tactical alliances had eroded the Hindutva base of the party. So, these compromises, struck to increase Lok Sabha seats, had to stop.

Advani can see that Hindu purity is no longer the only brand differentiator in coalition politics. The Sangh is unable to accept this. This tension continues.

article