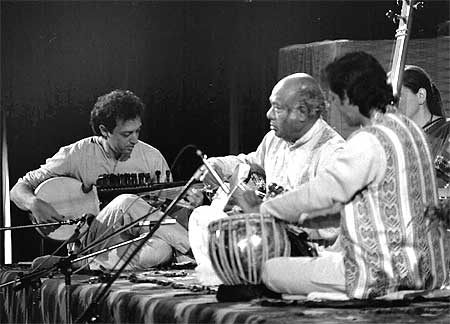

Ken Zuckerman recalls how he discovered sarod maestro Ali Akbar Khan during his odyssey in search of music.

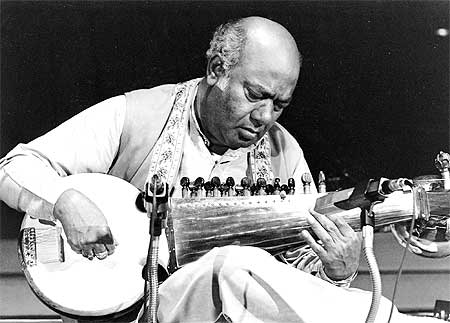

Thirty-seven years ago, I embarked on a life-altering musical and spiritual odyssey with the great maestro, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. The beginning of this journey was a clearly defined moment, filled with astonishment and inspiration. His passing away on June 18, 2009, was quite another kind of moment, one which shocked and saddened the entire music world. Now the odyssey will go on, perhaps without his physical presence, but certainly with all the precious lessons, experiences, and memories that have accumulated during all these years.

I am flooded by recollections of the time I spent with Khansahib, from the first moment I saw him perform in 1971, still as a teenager, to the last incredibly poignant lesson he gave us only hours before he passed away. I was just one of many curious Westerners who, somewhat by accident, were put in contact with his music. But at one moment during that first concert, it was as if a bolt of lightning hit me with the power of the music so deep, so compelling, and so spontaneous. I had to find out where this came from. I made the pilgrimage to California, and as soon as I began studying, I knew that this was the music I had been searching for my whole life.

My expectation of the Ali Akbar College was that it would be some kind of holy place like an ashram. However, what I first encountered was Khansahib, dressed in a Western flannel shirt and smoking a cigarette, teaching a large ensemble of singers and instrumentalists. It was surreal; and the melody, which he was in the process of composing, had the same beauty and hypnotic power as the music I had heard during that first concert.

I registered for the summer session of 1972, grabbed a sitar and sat myself down as close as I could get to the master. It began to hurt after 10 minutes; the pain was excruciating by the first half of the two-hour class. But I was too afraid to budge an inch in front of him. Then, I lost all sensation in my legs, and by the end of the class I could hardly stand up. Wow, I thought, this might be more difficult than I imagined. Then it got better, and then it got worse.

As soon as I began to get more used to the sitting position, my fingers started hurting (and sometimes bleeding), from the thin steel strings cutting into them. And the wire plectrum digging into my right index finger -- this was torture. At the same time, seeing Khansahib playing became even more captivating and I was tempted to switch from the sitar to the sarod. But I hesitated -- what a shame after a whole year of study, to have to go all the way back to the beginning. (Little did I suspect that in fact, I was still at the very beginning.) Then one night I had a dream in which Khansahib said to me, "What are you waiting for, just start playing the sarod." I did so the very next day.

I had many dreams about Khansahib, and once he surprised me by telling me that he had a dream that I was in. In the dream it seems he was learning from his father and was having trouble remembering one of the musical phrases. At one point he thought, "Oh, it doesn't matter, I can get the notation from Ken." How many times I had the same thought during his classes and was so thankful for some of the other students who had the notation!

One day, after having studied for several years, Khansahib surprised me by greeting me with my name. I was so happy and touched that in spite of the hundreds of students coming and going, he was getting to know me at the same that I was becoming more and more immersed in his teaching. Then there was the time when during a vocal class, he requested each one of us to sing alone. As if that weren't terrifying enough, he insisted that we each use the microphone, and he made sure that the volume was turned all the way up.

There was no escape, although we all wanted to melt and disappear into the carpet. One by one we all tried, and after I sang he said, "Very good. You are better, but you must get better still." It was a rare compliment, the first and one of the few he ever gave me directly. After cherishing it for a moment, I again dove into what seemed like an ocean of his knowledge, so often with a feeling that I would never get much deeper than the surface. Years went by and whenever I felt like I made a little progress, I immediately had the sinking feeling that the ocean was getting deeper all the time. Sometimes I despaired that I would fail, but he always taught us with such patience and inspiration that the pure joy of working in his presence renewed my hope.

In 1985, after seeing the growing interest in Indian music in Switzerland, Khansahib recommended that I open a branch of the Ali Akbar College in Basel.

I felt so honoured that he would trust me with this endeavor and at the same time, I was afraid of the challenge. In December, just after the birth of my first daughter, he arrived for the first of what would turn out to be many memorable seminars and European concert tours. But there were some growing pains and I made some mistakes. One evening Khansahib was so upset that he spent several hours lambasting me. He even constructed a "composition" as musically as one of his performances. The main theme was, 'But Ken, how could you do this to me?'

After each variation, during which he would elaborate how I had messed things up, he would always come back to the main theme, 'But Ken, how could you'. I was devastated and at one point broke down in tears. Then, almost as if he was waiting for that breaking point, he said, "Ken, I'm doing this because I love you and I want you to grow." I replied that he could have just told me what he wanted earlier. Then he said, "It doesn't matter what I say, you have to know what I want." I looked at him, first in disbelief, and then I understood that he was inviting me to change my entire view of the world. I slowly realised that Khansahib was demanding me to perceive something more subtle than just his words, to hear more of the microtones in between the notes and to sense the rhythms that are hidden in the shadows of the beats. From then on, everything was different, and I felt closer than ever to him and his teaching.

I, and for that matter all those who learned from Khansahib, could spend years just remembering everything we experienced with him. But what about the future? When I think back on what we learned for all these years, I wonder how can we ever thank this man for everything he has given us!

I remember his words, which have always been so inspiring to all of his students and disciples, and which now take on an even more challenging meaning: "My father learned from a great teacher and we always keep the tradition of things, like a father to son, or students and disciples. Therefore I want to keep what my father learned; I don't want it to die. It must spread all over the world."

What better way to thank Khansahib than to pass on to others, whatever we were able to learn from him.

And so the odyssey will go on.

Ken Zuckerman has been a disciple of Ustad Ali Akbar Khan since 1972. He lives in Switzerland where he directs the Ali Akbar College of Music in Basel. He is also a professor at the Music Conservatory of Basel, where he gives courses in North Indian classical music and Western music from the Middle Ages. He performs extensively in Europe, India and the US.