| « Back to article | Print this article |

The American behind 26/11 -- and how the US did not stop him

In the first of a four-part series, ProPublica's Sebastian Rotella reveals how David Coleman Headley turned from a United States Drug Enforcement Administration informant to a Lashkar-e-Tayiba operative, who played a key role in launching the most dreadful terror attack on Indian soil on November 26, 2008, and how America botched up chances to stop him. This story was co-published with PBS FRONTLINE.

Prologue: Justice Denied

During a meeting overseas last summer, a senior United States official and General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, the chief of Pakistan's armed forces, discussed a threat that has strained the troubled US-Pakistani relationship since the 2008 Mumbai attacks: the Lashkar-e-Tayiba militant group.

The senior US official expressed concern that Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi, a terrorist chief arrested for the brutal attacks in India, was still directing Lashkar operations while in custody, according to a US government memo viewed by ProPublica. Gen Kayani responded that Pakistan's spy agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate, had told prison authorities to better control Lakhvi's access to the outside world, the memo says. But Kayani rejected a US request that authorities take away the cell phone Lakhvi was using in jail, according to the memo to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and the National Security Council.

The meeting was emblematic of the lack of progress three years after Lashkar and the ISI allegedly teamed up to kill 166 people in Mumbai, the most sophisticated and spectacular terror strike since the September 11 attacks. The US government filed unprecedented charges against an ISI officer in the deaths of six Americans. Yet, Pakistani authorities have not arrested him or other accused masterminds. The failure to crack down on the jailed Lakhvi, whose trial has stalled, raises fears of new attacks on India and the West, counterterror officials say.

"Lakhvi is still the military chief of Lashkar," a US counterterror official said in an interview. "He is in custody but has not been replaced. And he still has access and ability to be the military chief. Don't assume a Western view of what custody is."

In the United States, stubborn questions persist about the case's star witness, David Coleman Headley, a confessed Lashkar operative and ISI spy. The Pakistani-American's testimony at a trial in Chicago this year revealed the ISI's role in the Mumbai attacks and a plot against Denmark. It was the strongest public evidence to date of ISI complicity in terrorism.

But the trial shed little light on Headley's past as a US Drug Enforcement Administration informant and the failure of US agencies to pursue repeated warnings over seven years that could have stopped his lethal odyssey sooner -- and perhaps prevented the Mumbai attack.

US officials say Headley simply slipped through the cracks. If that is true, his story is a trail of bureaucratic dysfunction. But if his ties to the US government were more extensive than disclosed -- as widely believed in India -- an operative may have gone rogue with tragic results. Both scenarios reveal the kind of breakdowns that the government has spent billions to correct since the Sept 11 attacks.

The Obama administration has not discussed results of an internal review of the case conducted last year, or disclosed whether any officials have been held accountable.

Click NEXT to read further...

The American behind 26/11 -- and how the US did not stop him

During an interview in Delhi, former Indian home secretary GK Pillai asserted that US authorities know more about Headley than they have publicly stated. Several senior Indian security officials said they believe that US warnings provided to India before the Mumbai attacks came partly from knowledge of Headley's activities. They believe he remained a US operative.

"David Coleman Headley, in my opinion, was a double agent," said Pillai, who served in the top security post until this past summer. "He was working for both the US and for Lashkar and the ISI."

The Central Investigation Agency, Federal Bureau of Investigation and DEA deny such allegations.

An investigation by ProPublica and FRONTLINE during the past year did not find proof that Headley was working as a US agent at the time of the attacks. But it did reveal new contradictions between the official version of events, Headley's sworn testimony and detailed accounts of officials and others involved in the case. The reporting also turned up previously undisclosed opportunities for US agencies to identify Headley as a terrorist threat, and new details about already-reported warnings.

US and foreign officials say his role as an informant or ex-informant helped him elude detection as he was training in Pakistani terror camps and travelling back and forth to Mumbai to scout targets. And three counterterror sources say US agencies learned enough about him to glean fragments of intelligence that contributed to the warnings to India about a developing plot against Mumbai.

In contrast, some US officials say spotting a threat is harder than it seems. Glimmers of advance knowledge are part of the landscape of terrorism. In cases such as the Sept 11 attacks and the 2004 Madrid train bombings, security forces had detected some of the suspects but not their plots.

"I just have to dispel some of these notions," said Philip Mudd, a former top national security official at the FBI. "We look at a grain of sand and say ... 'why couldn't you put together the whole conspiracy when you saw that grain of sand?' Well, you got to reverse it. Every day coming into a threat brief, you're not looking at a grain of sand and building a beach. You're looking at a beach and trying to find a grain of sand."

New information about the case comes partly from the DEA. After months of silence, DEA officials recently granted an interview with a ProPublica reporter and went over a timeline based on records about their former informant. The DEA officials said Headley's relationship with the anti-drug agency was more limited than has been widely described.

The American behind 26/11 -- and how the US did not stop him

The DEA officially deactivated Headley as a confidential source on March 27, 2002, according to a senior DEA official. That was weeks after he began training in Lashkar terror camps in Pakistan and six years before the Mumbai attacks. The senior official denied assertions that Headley had worked for the DEA in Pakistan while he trained with Lashkar in 2002 and beyond.

"The DEA did not send David Coleman Headley to Pakistan for the purpose of collecting post-9/11 information on terrorism or drugs," the senior DEA official said.

The denial adds another version to a murky story. Officials at other US agencies say Headley remained a DEA operative in some capacity until as late as 2005. Headley has testified that he did not stop working for the DEA until September 2002, when he had done two stints in the Lashkar camps.

Some US officials and others involved say the government ended Headley's probation for a drug conviction three years early in November 2001 to shift him from anti-drug work to gathering intelligence in Pakistan. They say the DEA discussed him with other agencies as a potential asset because of his links to Pakistan -- including a supposed high-ranking relative in the ISI.

A senior European counterterror official, who has investigated Headley in recent years, thinks the American became an intelligence operative focused on terrorism.

"I don't feel we got the whole story about Headley as an informant from the Americans," the official said. "I think he was a drug informant and also some other kind of an informant."

The transition from registered law enforcement source to secret counterterrorism operative would help explain the contradictory versions. But the duration and nature of intelligence work by Headley, if it was done, remain unknown.

Federal prosecutors and investigators declined to be interviewed on the record for this story. Pakistani officials, who also refused to be interviewed, have said they have cracked down on Lashkar and have denied that the ISI was involved in the Mumbai attacks.

Nonetheless, ProPublica and FRONTLINE talked to US and foreign counterterror officials and other well-informed sources while reporting in the United States, India, Pakistan and Europe. A number of those officials and sources requested anonymity for their security or because they were not authorised to speak publicly about the sensitive case.

Headley was a wildly elusive figure who juggled allegiances with militant groups and security agencies, manipulating and betraying wives, friends and allies. He played a crucial role in an attack that had resounding international repercussions. And his unprecedented confessions opened a door into the secret world of terrorism and counterterrorism in South Asia -- and closer to home.

The American behind 26/11-- and how the US did not stop him

Chapter 1: "The Prince"

David Coleman Headley is not his original name.

The 51-year-old was born Daood Gilani in Washington, DC. His father, Syed Saleem Gilani, was a renowned Pakistani broadcaster. His mother, Serrill Headley, was a free spirit from a wealthy Philadelphia family. They moved to Pakistan when he was a baby, but the parents divorced and Serrill returned alone.

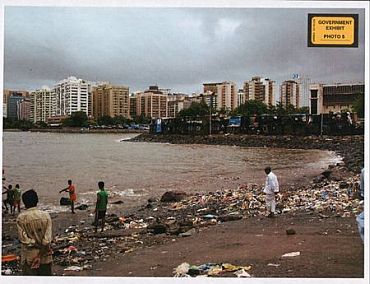

Headley grew up in an environment of Pakistani nationalism and Islamic conservatism. During a war with India in 1971, a stray bomb hit his elementary school in Karachi, killing two people. The incident stoked his hatred of India, according to his later accounts.

Headley attended the Hasan Abdal Cadet College, where he met his friend Tahawwur Rana. During testimony at Rana's trial this year in Chicago, Headley said he was proud of studying at the elite military school, though he did not graduate. He described Rana as a "very good" student and himself as "very bad."

Rana's wife recalled an anecdote about Headley's approach to morning prayers.

"Dave, he knocks on all the doors of students and he says, 'Get up, get up, it's time for prayer'," Samraz Rana said in an interview. "And then when everybody gets up, he went to his room and went to sleep, you know. So he was laughing, he was like that."

Headley clashed with his Pakistani stepmother. At 17, he returned Philadelphia to live with his mother. She owned the Khyber Pass, a trendy club that featured tarot readings and jazz and folk music. Her son helped manage the bar. He was tall and smooth and had a striking characteristic: One eye was brown, the other blue.

Employees nicknamed him "The Prince."

"I think he was in culture shock," said Djuna Wojton, a friend of his mother. "He spoke like with almost a British accent. And he was very well-mannered and very proper and polite."

Headley enrolled at Valley Forge Military Academy & College but did not last long there. He studied at a community college and slid into heroin addiction. His first encounter with the law happened during a visit to Pakistan when he was 24. He used his friend Rana, then a Pakistani army medical student, as an unwitting shield.

The two drove to the tribal areas, where Headley bought half a kilogramme of heroin and smuggled it back to Lahore, according to the DEA and Headley's testimony. He thought Rana's military ID card would prevent a police search if they were stopped, according to his testimony.

Days later, police in Lahore arrested Headley for drug possession, according to his testimony and US officials. He somehow beat the charges.

In 1988, police caught him at the Frankfurt, Germany, airport en route to Philadelphia with two kilos of heroin hidden in a suitcase. The DEA took over, and he made a deal on the spot. His partners in Philadelphia got eight and 10 years in prison. He got four years.

It would become a pattern, said former CIA officer Marc Sageman, a respected terrorism expert who was a consultant for Rana's defence.

"He just turns around immediately and betrays everybody when it's convenient for him," said Sageman.

Struggling with addiction, Headley spent six months in prison for a probation violation in 1995. He moved to New York, where he bought and operated video stores. Despite his criminal record, he managed to avoid prosecution a year later when police on Long Island arrested him for allegedly assaulting and threatening the former boyfriend of his new Canadian girlfriend, according to Nassau County authorities.

The American behind 26/11 -- and how the US did not stop him

Chapter 2: Informant and Militant

Headley overcame his addiction but not his taste for drug money.

In early 1997, the DEA arrested him in a sting at a Manhattan hotel. He signed up as a confidential DEA informant and was out on bail by August. In January 1998, the DEA sent Headley to Pakistan to dispel suspicions among traffickers about his absence. He used his wealthy father's house in Lahore to meet with suppliers, and gathered useful intelligence during his first and only DEA-funded mission in Pakistan, the senior DEA official said.

"This was the only trip at the DEA's behest," the senior official said.

During his first 16 months as an informant, Headley infiltrated Pakistani heroin trafficking networks, generating five arrests and the seizure of 2½ kilos of heroin, the DEA says.

There were warning signs, however. He broke the rules by trying to set up dealers with jailhouse phone calls that were not monitored by agents, according to court records. He angled for leverage with his handlers, according to a close associate from that period.

"The DEA agents liked him," the associate said. "He would brag about it. He was manipulating them. He said he had them in his pocket."

One defendant was acquitted on grounds of entrapment, a rare finding in a drug case. Ikram Haq was a mentally impaired Pakistani immigrant. His lawyer, Sam Schmidt, convinced the jury that Headley conned his client into a heroin deal.

"My impression of him was a person who was in many ways a sociopath," Schmidt said, "that he would be able to say anything that he thought would work to his benefit."

Headley served another eight months in prison. He became a more devout Muslim behind bars, according to his associate. Soon after his release in 1999, probation officials permitted him to travel to Pakistan for a few weeks for an arranged marriage. His new wife remained in his family hometown of Lahore.

Headley returned to New York and resumed work for the DEA in early 2000. That April, he went undercover in an operation against Pakistani traffickers that resulted in the seizure of a kilo of heroin, according to the senior DEA official.

At the same time, Headley immersed himself in the ideology of Lashkar-e-Tayiba. He took trips to Pakistan without permission of the US authorities. And in the winter of 2000, he met Hafiz Saeed, the spiritual leader of Lashkar.

Saeed had built his group into a proxy army of the Pakistani security forces, which cultivated militant groups in the struggle against India. Lashkar was an ally of al Qaeda, but it was not illegal in Pakistan or the United States at the time.

Saeed made a statement that was Headley's epiphany: "One second spent in jihad is superior to 100 years of worship and prayer."

In New York, Headley recruited for Lashkar, prayed intensely and studied Arabic, according to his associate and other sources. Headley talked about getting ready for jihad overseas. He prepared to sell his stores, underwent laser eye surgery and took horseback riding lessons, which he said would be useful for mountain training camps.

"He was living on the Upper West Side," the associate said, "sleeping on the floor, eating rice and beans, acting really weird. He started collecting money for Lashkar, saying how great it was."

Headley later testified that he told his DEA handler about his views about the disputed territory of Kashmir, Lashkar's main battleground. But the senior DEA official insisted that agents did not know about his travel to Pakistan or notice his radicalisation.

On Sept 6, 2001, Headley signed up to work another year as a DEA informant, according to the senior DEA official.