Photographs: Courtesy: PBS Frontline

In the fourth and concluding part of the series ProPublica's Sebastian Rotella talks about how Laskar-e-Tayiba operative David Coleman Headley was finally nabbed by United States law enforcement agencies, but only after he hoodwinked them for seven years. But the epilogue in the story is rather like the prologue: full of impunity and mystery.

Chapter 7: "Congrats On Your Graduation"

On the night of Nov 26, 2008, Lashkar-e-Tayiba David Coleman Headley was at home in Lahore when his handler Sajid Mir sent him a text message. It said, "Turn on your television."

The siege of Mumbai lasted three excruciating days. The 10-man attack team arrived by sea, landing at a fishermen's slum chosen by Headley for its strategic location. The young gunmen had never been to India. They were guided by Headley's videos and written reports, his provision of GPS coordinates and his work with a Pakistani navy frogman on the maritime approach.

Part 1: The American behind 26/11 -- and how the US did not stop him

Part 2: Headley, America's 'hip-pocket' source in Pakistan who backfired

Part 3: From Daood Gilani to David Headley: A Pak spy is born

Mir and other Lashkar bosses directed the slaughter by phone from a command post in Karachi. Their calls were intercepted by Indian intelligence and have been subsequently broadcast in international television reports.

Headley watched the coverage with his Moroccan wife; they had reconciled weeks earlier. He got a celebratory email from his Pakistani wife, whom he had moved with their children to Chicago in September. The wife knew about his reconnaissance and praised him in an email using coded language, according to court testimony.

"Congrats on your graduation," the wife wrote on Nov 28, according to court documents. "Graduation ceremony is really great. Watched the movie the whole day."

Headley was already thinking about his next mission.

In October, Major Iqbal and Mir had visited him at home, the first time he had seen his Inter-Services Intelligence and Lashkar handlers together, according to Headley's testimony. They wanted to take their holy war to Europe. They assigned him to scout the Jyllands-Posten newspaper of Denmark, a terrorist target because it had published cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed.

Headley visited his family in Chicago over the Christmas holiday. He learned that yet another tipster had gone to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, according to his testimony. It was a female friend of his mother, who had died earlier in the year. Apparently motivated by news of the Mumbai attacks, the woman contacted the Wilmington, Delware, FBI office, which passed the lead to the Philadelphia field office.

Interviewed on December 1, the tipster said Headley's mother had told her years earlier that her son was fighting alongside militants in Pakistan. The tipster said she believed he was still involved in militant activity. FBI agents reviewed records and found "most or all" of the warnings dating back to 2001, according to a senior US law enforcement official.

On Dec 21, agents interviewed Farid Gilani, Headley's cousin in Philadelphia. He deceived them by saying Headley was in Pakistan, according to testimony. The cousin called Headley in Chicago to alert him, according to testimony. In an email to a militant in Pakistan, Headley speculated that the FBI's interest was related to the allegations months earlier at the US embassy by his Moroccan wife, whom he called "M2."

"So I think that it is OK, just routine, because of what M2 said before," Headley wrote on Dec 24.

This story was co-published with PBS FRONTLINE.

...

Rise and fall of Headley: From LeT to Chicago jail

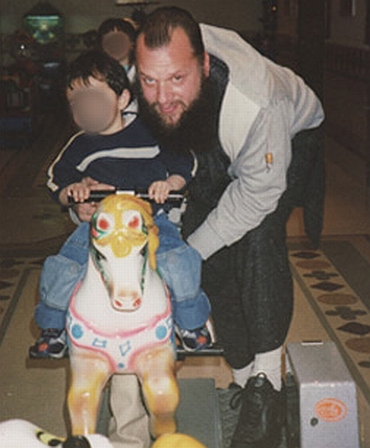

Image: Headley has had three wives -- some of the relationships overlapping -- but only had children with his Pakistani wife Shazia, with whom he had an arranged marriage in 1999Photographs: Courtesy: PBS Frontline

Lashkar had just pulled off a terror spectacular, killing six Americans. Headley was an American. Half a dozen leads over seven years painted a picture connecting him to Lashkar and the Taj Hotel.

Yet, the FBI did not go find him in Chicago. Agents put the inquiry on hold because they thought he was out of the country, officials say.

"It is surprising that after Mumbai the FBI didn't pick up on him," a senior US counterterror official said. "You would have thought they would have scrubbed records for anyone in the US with Lashkar connections and tried to work him as a source or investigative lead."

Headley went to Copenhagen, Denmark, in mid-January of 2009. There was no high life this time. He stayed at the Hotel Nebo, a discreet establishment behind the central train station on a strip frequented by prostitutes and drug addicts.

But his approach was the same. He did video surveillance, assessed target areas and took notes. He looked into renting an apartment as a safe house for an attack team. Using Tahawwur Rana's firm as a cover again, he talked to a young Danish woman about a possible job as a secretary, according to European counter-terror officials and interviews in Denmark.

On Jan 20, he went to the newspaper offices in historic King's Square.

"I looked up, and a gentleman, a businessman, walked through the door," recalled Gitte Johansen, who was the receptionist in the street-level lobby. "He looked as if he was, you know, he had a certain goal ... as if he had a meeting, for instance. So I let him through the second door. ... He was tall, light-tanned, business suit and tie, very friendly and very serious but in a friendly way, explaining to me that he was in Denmark because of his business. He had moved from US to Denmark, and he wanted to buy space in our newspaper for advertisement."

Headley met with an advertising representative in the lobby for about 15 minutes. He drove to the city of Aarhus, cased the newspaper building there and met with another advertising representative, according to investigators and newspaper employees.

Headley returned to Pakistan and met with his handlers. In March, they decided to put the plot on hold. Responding to foreign pressure, Pakistani authorities had arrested Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi -- Lashkar's military leader -- and a few other suspects.

Headley had grown disenchanted with Lashkar. He shifted to Al Qaeda with the help of a friend named Abderrehman Syed, a former Army major who had left Lashkar.

"He said they were conducting the ISI's jihad and we should conduct God's jihad," Headley testified.

Despite his declarations, Syed retained contact with an ISI colonel who had been his handler, according to investigative documents. Syed, in turn, became Headley's latest handler. He introduced him to Ilyas Kashmiri, a notorious Pakistani terror chief, who took over sponsorship of the Denmark plot, according to Headley's testimony and other evidence.

Kashmiri was enthusiastic. He gave Headley the names of militants in Britain and Sweden who could help with funds and weapons and possibly take part in an attack. Kashmiri said the gunmen should storm the newspaper, Mumbai-style, then put on a media spectacle.

He wanted them to behead hostages and throw the heads out of windows into King's Square.

Rise and fall of Headley: From LeT to Chicago jail

Image: Jyllands-Posten newspaper of Denmark, which the Lashkar planned to attackChapter 8: The Downfall

Back in Chicago that summer, Headley prepared for his second reconnaissance trip to Denmark.

He communicated with two Al Qaeda operatives in Britain referred to him by Kashmiri. Once again, Headley strayed into a law enforcement net. This time, though, he didn't slip out.

In July, British intelligence learned about his impending visit and notified the FBI. On July 23, the FBI passed a lead to US Customs and Border Protection for assistance: A man named David, possibly an American, a suspected associate of Lashkar and Al Qaeda, would soon fly to Manchester via Chicago and Frankfurt, according to US officials.

Border agency analysts began sifting through hundreds of possible candidates on passenger lists. The next day, another detail surfaced: The suspect would fly Lufthansa. An analyst quickly zeroed in and identified Headley because of his past travel and stops at secondary inspection. The FBI's Chicago field office took charge of the investigation and coordinated with European counterparts.

Headley's meeting in the English town of Derby on July 26 did not go well. The militants, known as Simon and Bash, didn't want to participate in the attack and couldn't supply weapons. They gave him about $15,000 (approx Rs 7.8 lakh) to finance the plot, according to his testimony and other evidence.

Headley continued to Stockholm to see a veteran militant named Farid. The reception was worse. An agitated Farid told Headley to leave him alone because Swedish police had him under tight surveillance, according to European counterterror officials. The officials say Farid declared: "Sorry, brother, I can't help you."

A discouraged Headley took a train to Copenhagen on July 31. Danish intelligence was waiting for him. Danish agents shadowed his every step. They monitored his calls and his visits to seedy neighborhoods to talk to drug dealers about acquiring guns. When he rented a bicycle, they followed on bikes, according to a senior European counterterror official.

"He rode up and down the street past an army barracks, filming with a video camera," the European official said. "That raised eyebrows."

Headley returned via Atlanta on Aug 5. He was on a watch list now. Airport inspectors questioned him, then let him go so the FBI could continue surveillance. Investigators soon came to suspect he had been involved in the Mumbai attacks. They dug into his past, debriefing his former DEA handler and reviewing records of prior inquiries, officials say.

The two-month surveillance operation drew high-level interest, according to Mudd, the former top FBI national security official.

"I remember hearing about the case and it immediately boiling up to the top of our morning threat briefings," Mudd said. "We sat down every morning with the director of the FBI and with the attorney general to talk about what's happening in the United States. ... And all of a sudden you have ... an (Al Qaeda-) affiliated organisation, Laskhar-e-Tayiba, that had a presence in the heartland of the United States and not only a presence but a man who'd been involved in a murder of 160-something people."

Rise and fall of Headley: From LeT to Chicago jail

Image: The Taj Mahal Hotel during the 26/11 attacksOn Oct 9, the FBI arrested Headley at Chicago's O'Hare Airport. He was bound for Pakistan with his Denmark videos in his luggage. He had planned to meet with his terror bosses and return to Denmark. He had been talking about an attack he could do himself, perhaps assassinating an editor, according to officials and testimony.

Headley's former DEA handler came to Chicago for the arrest. The drug agent's presence sent an unspoken message: time to cooperate. FBI agents read Headley his rights, and he started talking. He kept talking for 15 days.

His interrogation and later trial testimony provided unprecedented evidence on Lashkar, the ISI, Al Qaeda, plots, targets, leaders, methods. Supervised by agents, he communicated with people overseas in attempts to lure Mir out of Pakistan and set a trap for a militant in Germany, according to testimony.

None of it worked. So Headley turned on Rana, his old friend. He revealed that Rana had helped him use his immigration firm as cover during the Mumbai and Denmark plots. He testified against Rana at the Chicago trial, which ended with a conviction on two of three counts of material support of terrorism.

Headley agreed to a plea bargain that spared him from the death penalty and extradition to India, Denmark or Pakistan. He now faces a maximum sentence of life in prison. According to investigators, he has steadfastly protected one person: his Pakistani wife, Shazia.

"His condition when he spoke to us was that he accepted no questions about Shazia," said the Indian counterterror official familiar with the Indian interrogation of Headley. "He said: 'She is the only one who has given me four children. Despite my philandering, she has been faithful. She has been loyal to me. She is a devoted Muslim. I admire her.'"

Rise and fall of Headley: From LeT to Chicago jail

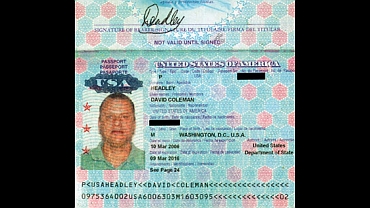

Image: Daood Gilani applied for a name change in 2005; six months later, he was David Coleman HeadleyPhotographs: Courtesy: PBS Frontline

Epilogue: Questions And Contradictions

The epilogue has been like the prologue: a trail of impunity and mystery.

In addition to Major Iqbal, Mir and two other accused Lashkar masterminds were indicted this year by US federal prosecutors. Despite abundant evidence, Pakistan has not arrested or charged them -- or half a dozen other top suspects, officials say.

The targeting of the West in Mumbai and Denmark has raised fears that Lashkar could become a more formidable threat than a diminished Al Qaeda.

"Now we wonder if they think about the political ramifications of an attack on the US or the West," a US counterterror official said. "The presumption has been that they did, or that ISI did and controlled their targeting with this mindset. Is it really a constraint now? Do they really worry about a crackdown if they do another attack on the West? What would be going too far for them?"

Pakistan's Federal Investigative Agency, the equivalent of the FBI, is in charge of the investigation. But in reality, no one in Pakistan is trying to arrest Major Iqbal, Sajid Mir or the others, US and Indian officials say.

Pakistani officials deny that Major Iqbal was an ISI officer. That only makes it harder to understand why he has not been arrested. It raises questions about the potential knowledge and involvement of ISI chiefs.

The director of the ISI during the period in which the Mumbai plot developed, Gen Nadeem Taj, stepped down two months before the 2008 attacks as the result of pressure from foreign governments concerned that he was soft on militants, according to Western officials. Taj previously was the top military officer in the garrison city of Abbottabad during the period that Al Qaeda's Osama bin Laden established himself in hiding there, officials say.

"We, as a government, want to say that the Pakistanis are in our corner," said Faddis, the former CIA counterterror chief. "Obviously, it's way more complicated than that. And there are a whole bunch of folks in Pakistan and in the ISI who are not at all on the same sheet of music with us here. So even when they have cooperated with us over the years, it is often basically because they've been forced to. ...Then we have a number of individuals within ISI who are very sympathetic to the folks that we are targeting."

The official US version of the case presents contradictions as well.

Rise and fall of Headley: From LeT to Chicago jail

Image: On Oct. 9, 2009, as Headley attemped to go back to Pakistan, federal agents arrested him at Chicago's O'Hare AirportPhotographs: Courtesy: PBS Frontline

In response to ProPublica stories last year detailing the 2005 tip about Headley, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence led a multiagency review of Headley's contacts with the US government. But the DNI has declined to discuss the findings or any consequences. During the review process, agencies pointed fingers at each other, according to knowledgeable officials.

Although the litany of warnings about Headley paints a grim picture, officials at the FBI and other agencies assert that the allegations lacked specificity. They say Lashkar was not seen as a major threat before Mumbai. They cite the sheer volume of terror-related leads, especially after the Sept 11 attacks. And they say some problems in tracking threats revealed by the case have been corrected as systems have improved.

But the questions linger. And the man at the centre of the labyrinth is fittingly contradictory and enigmatic.

Headley slid among personas and cultures with ease, not completely at home in any of them. He spouted hateful anti-Semitic and anti-Indian rhetoric but loved the films of the Coen brothers and Bollywood. He veered from caring and generous to cold and treacherous. He washed out of military schools and clashed with authority figures, yet saw himself as a warrior and hoped his son would become a special forces commando.

Investigators and experts suggest a variety of motivations driving him: ideology, money, women, glory and, above all, an appetite for adrenalin.

"The pattern is risk-taking," said Sageman. "He wants to live for the moment. He is not above taking crazy risks. ... He just likes the adventure. He loves the game."

Contributing: Sabrina Shankman and David Montero for PBS FRONTLINE.

article