| « Back to article | Print this article |

'People in India are more at peace with themselves'

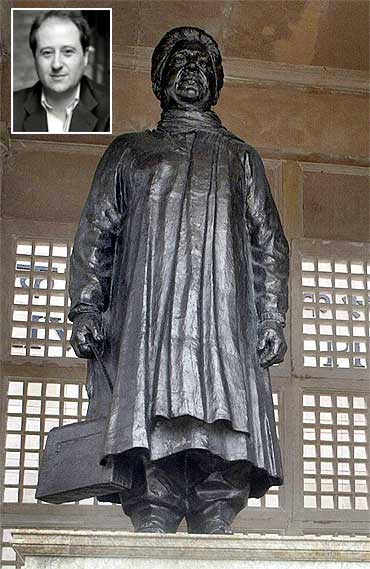

In the book that took almost ten years to write, the award-winning writer-historian, who is married to an Indian, comes out as a 'friend' of India. While writing about the country's economic development, he examines closely and critically the composition of the current Parliament, people's lives in far-flung areas and discusses the future of the marginalised in India.

However, many critics have attacked the book for admitting 'few discordant voices,' while others have criticised French's claim on the book being 'an intimate biography of 1.2 billion people,' when it excludes -- cricket and Bollywood -- the two enduring fetishes of the Indian people.

French has attracted so much attention for his version of today's India that it speaks of his importance in the world of ideas and words. A decade back, he had contributed significantly in understanding the Partition of India. His book Liberty or Death: India's Journey to Independence and Division has become a must read for people looking for an informed perspective of India's recent history.

French has attracted some negative reviews because some critics differ with him strongly in his narratives of 'why is India like it is today?' In an exclusive interview with rediff.com's Sheela Bhatt, French comes alive with straight responses about India.

You have tried to cover a wide range of subjects in your book. As you know India has been famous for the spiritual quest of its people. As you see India today, do you find that it is spiritual, even now? 'Spiritual' in the sense it was famous for in the past?

India is deeply spiritual.

Even now?

There are two different issues here. In the past, India was famous for its spirituality and poverty. The image of Mahatma Gandhi was central to the foreigners' idea of India. But, now India is a totally different country.

In the last 20 years so much has changed, but the country remains profoundly religious. My impression is that almost everybody who has some family religious tradition will retain it in some way and will keep their deity in some place. They will keep a connection to their deity.

I am broadly speaking about Hinduism here. But I also think the way in which Christianity and Islam work in India is often more broad and wide ranging than in some other countries. Having seen Christian churches in different parts of India, I came to know that some elements of Hinduism seem to have been incorporated in it.

Another point is the fact that though far more people are wealthier now does not mean that they have turned away from religion. The amount of money going to a temple or people taking time off to go on pilgrimages is a phenomenon of modern India also.

'It's quite possible to be a deep follower of Hinduism and, yet, be materialistic'

Of course, there is materialism. But that's the great thing about Hinduism where materialism is incorporated into religion. That's the great difference between Christianity where it is impossible for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven.

It's quite possible to be a deep follower of Hinduism and, yet, to be materialistic and you see people using religious methods to obtain wealth.

It was quite disturbing to read the story of Venkatesh, the quarry worker near Mysore, and his employer Puttaswamy Gowda who chained him and kept him as a slave for many years. You have written in minute detail about him, but some may find that you are not tearing him (Gowda) apart. There is a human touch in the narration, but why not take it to a logical conclusion.

I am.

Because India is so big, of course, you can always find horror stories. The reason why you have to be optimistic is because you take the country as a whole. You step back and look at the country as a whole. It seems that the trajectory is positive. That's the reason for my optimism.

I am not saying that cruelty isn't there. I am just saying that overall things are heading in a better direction. Take for example, the 1970s -- what aspirations did Indians have at that time when the GDP was 0.1 per cent? What aspirations can you have?

'In India everybody has an opinion... 5 opinions'

How do you see Chinese and Indians handling their country's 9 per cent growth? How are people in Shanghai and Bangalore handling their money?

That's an interesting question. Both China and India have their traditional savings and tradition of accumulating wealth. It's in direct contrast with the US where everything is built on credit. The Chinese government is buying US treasury bonds and financing the debt. But in China people cannot speak freely.

In China people don't have the tradition of speaking freely. Whether you go back to Confucianism as a doctrine or whether you look at Maoist Communism or their idea of loyal opposition, the idea where you can freely debate different views in the public space is absent.

That means interviewing people in China is a very different process. People are much more restrained and careful about expressing an opinion. In India everybody has an opinion... five opinions. Everybody would express what they have to say.

My impression is that people in India are at more peace with themselves.

It's just the feeling that I have. In China after the Cultural Revolution many traditions and practices were destroyed. It is very difficult to recreate it. So you have to borrow it from elsewhere.

In India, many traditions of communities go back to 500 years. I was in Bangalore three days ago. I met somebody who was heading a major technology project. He and his wife have created two social start-ups. I went for a vegetarian lunch to their house -- a nice house, but, quite a simple one.

They could have gone after more money, but I could see there was an ease and interest in other things. They had interests in wider ideas of how society works. They were interested in knowing if some of these ideas could be implemented through social mechanism.

Their personal interest was not in making cash. It seemed to me that this came out of particular cultural and social conditions specific to the society in India.

'Symbolically, Mayawati is hugely important'

I would say some people are over-confident. I think the speed and turnaround is so rapid that people sometimes forget that a large proportion is excluded and may seem that their own rapid success is going to be replicated indefinitely.

I was speaking to somebody about NREGA (the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme). He said I would never ever need NREGA. I suppose you never know what's lying ahead for you. You don't know what's lies in the future.

In your book when you are writing about the not-so-privileged people, one thing that comes out is violence. Like, when you talk about the caste issue. Do you see violence very dominant in India? Mob psychology is quickly triggered, also, due to the violence inside an individual's mind. Is it?

It is. I think, often people don't speak frankly about caste and its implications, particularly, in the English-speaking liberal part of India, caste is discounted. You note it in a way, that's a kind of public dishonesty.

The same people, who you might say are so important, so often marry within their own community. There is so much unspoken subtext in this. I think the implication of the exclusion of hundreds of thousands of years is something that people have not yet come to terms with.

The idea and a level of Dalit assertion fascinate me. For example, if you go to UP (Uttar Pradesh) the difference with which people speak about themselves compared to when I first visited UP is very significant. People are standing up. They are demanding things. They are not willing to be put down.

That's why I believe that Mayawati is such an important politician. People often are scornful of Mayawati. They say why should she have a garland of notes or that she hasn't run the administration properly. But the reason I write about her in some detail is because I think, she symbolically is hugely important.

You should never underestimate the power of an idea. The idea that she is putting forward to tens of millions of people, who were not oppressed in their lifetime, but have been oppressed for generations is remarkable.

I think that's going to create a revolution or is creating a revolution and a consequence of that is not yet clear. It's going to get further.

I have written about the scientific study of caste. A new proof that caste is not genetic and also that it's not as old as people think. Comparatively, it's a recent social invention.

If the caste system was thousands of years old, it would have come out genetically. But it hasn't. I don't think there would be a violent revolution. But I think there is a revolution going on inside people's minds.

You can see that in UP, in the way people behave. Again, you can look at Mayawati's huge stone cultural park. You can say...well, it looks bad, that she chopped down so many trees for it or why should she build so many elephants or why did she need to put up all those statutes of herself, Dr Ambedkar, Gautam Buddha and Kanshi Ram... why did she need to do these?

But yet to people who come from a disadvantaged community, it has very important representative value. You can see that in a way people speak about it.

It may horrify the elite, but it may not horrify people who come from a completely different background.

Part II of the Interview: 'Rajesh Talwar is an innocent man'