| « Back to article | Print this article |

Osama raid forgotten; US, Pakistan are pals again

B Raman decodes the complicated chain of accusations, denials and public avowals of friendship that characterises the relationship between the United States and Pakistan

Secret commitments by both the political and military leadership to cooperate with the United States in counter-terrorism, ritual denial of such commitments in public statements, dragging its feet in the implementation of the commitments and making fresh commitments. That has been the history of Pakistan's counter-terrorism cooperation with the US. That history continues after the death of Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden.

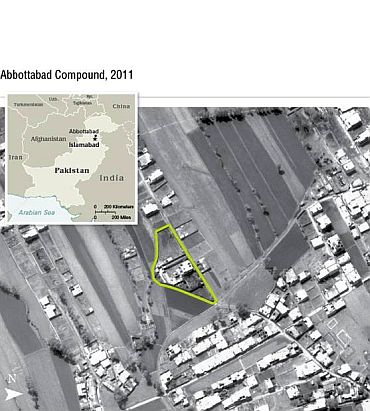

The counter-terrorism cooperation between the US and Pakistan, which had been stalled following the raid by American naval commandos on the residential hideout of Osama bin Laden at Abbottabad in the Khyber Pakhtoonkwa province on May 2, have been restarted following a vigorous push given by Senator John Kerry, chairman of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee, who visited Islamabad for talks on May 15 and 16, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Admiral Mike Mullen, chairman, US Joint Chiefs of Staff, who followed up on Kerry's talks during a short visit to Islamabad on May 27.

After Kerry's visit, the two countries initiated measures to bring down the tensions which had arisen after the Abbottabad raid. Pakistan handed over to the US the half-destroyed helicopter which the naval commandos had blown up on May 2 when the pilot reportedly lost control and hit the compound wall of Osama's residence while bringing it down.

Half-destroyed chopper handed over to the US

The US was worried that Pakistan might give China access to the half-destroyed chopper to enable them to study it. The handing over of the chopper to the US authorities was one of the demands made by Kerry during his talks with the Pakistani authorities. Before Clinton arrived, the Americans were allowed to take the half-destroyed chopper out of Pakistan.

Before the arrival of Clinton, the Pakistani authorities also allowed a team of the Central Intelligence Agency to jointly interrogate the three wives of Osama who were taken into custody by the Pakistani authorities after the naval commandos had left Abbottabad.

Originally, the US plan was to take the wives to Afghanistan for interrogation, but this was abandoned by the US after its commandos lost a chopper. Pakistan also accepted the US's request to allow a team from the CIA to make a detailed inspection of Osama's residence.

While the naval commandos had removed from Osama's residence all documents, computers and computer material which they had found there, they were not able to make a detailed inspection of the house because of the short time at their disposal. They will now be able to do so, though belatedly.

US toning down its presence in Pakistan

There were two gestures from the US's side. The first was the toning down of the suspicions of possible complicity with Osama at the higher levels of the Pakistani government -- particularly the Inter Services Intelligence -- which enabled him to live undetected for over five years at Abbottabad and direct the command and control of the Al Qaeda from there.

Clinton has now ruled out the possibility of any complicity at senior levels, but has continued to stress the need for a thorough enquiry regarding any possible complicity at the lower echelons. The Pakistani Army and the ISI do not find any difficulty in accepting this demand.

The second US gesture was to agree to downsize the clandestine presence of US intelligence and special forces personnel in Pakistan to coordinate the counter-terrorism co-operation with their Pakistani counterparts. The US had agreed to make a small reduction in the number of US clandestine personnel posted in Pakistan even before the Abbottabad raid.

This was in response to a Pakistani demand after the January incident involving Raymond Davis, a member of the administrative staff of the US consulate at Lahore, who had allegedly killed two Pakistanis who were following his car. This has now been followed up by a reported US decision to cut down its clandestine personnel further.

Did Pakistan know about the Abbottabad raid?

Apparently, after the death of Osama, the US does not feel the need for the presence of a large number of clandestine staff in Pakistani territory. Its decision to accommodate the Pakistani demand for further reduction should not affect its capability on the ground significantly.

Both Pakistani and US authorities have been embarrassed by the disclosure by Dawn daily about some diplomatic cables of 2008-09 released by WikiLeaks. These cables, which had been sent by Anne Patterson, the then US ambassador to Islamabad, to the US State Department clearly showed, firstly, that the Pakistani Army had allowed a much larger US clandestine presence than admitted so far not only in the Pashtun belt, but even in the GHQ in Rawalpindi, to enhance US-Pakistan counter-terrorism co-operation, and, secondly, that not only Pakistan's political leadership, but even its military leadership had tacitly allowed the US to operate its drones over the Federally-Administered Tribal Areas while openly criticising them as a violation of Pakistan's sovereignty.

If the army had tacitly agreed to instances of wanton US violation of Pakistani sovereignty in respect to the drone strikes, is it not legitimate to suspect as many, including me, are doing, that there must have been some tacit understanding related to the Abbottabad raid too? All this post-May 2 hysterics about the so-called violation of Pakistani sovereignty is a ritual meant to calm public opinion in Pakistan.

'Pakistan has to take decisive steps'

Citing US media reports, the Pakistani media reported as follows before Clinton's visit: Pakistan ordered the departure of up to 20 percent of the roughly 150 US Special Operations forces trainers in the wake of a series of differences between the two governments. Between 25 and 30 trainers were "told to leave" in the weeks before the US commando raid that killed Osama, apparently in response to the Raymond Davis incident.

During Clinton's talks in Islamabad, according to the Pakistani media, Islamabad agreed to intensify operations against the Al Qaeda and affiliated groups in its territory, while Washington softened its stance on 'unilateral action' against high-profile terrorist targets inside Pakistan by underscoring the importance of acting together against terrorists.

While there was no joint statement, Clinton told the media at the US embassy, 'We both recognise that there is still much more work required to be done and it is urgent. Today we discussed in even greater detail the cooperation to disrupt, dismantle and defeat Al Qaeda and to drive them from Pakistan and the region. We will do our part and we look to the government of Pakistan to take decisive steps in the days ahead. Joint action against Al Qaeda and its affiliates will make Pakistan, America and the world more safe and more secure.'

According to the Pakistani media, her media comments wavered between expression of acknowledgement of the sacrifices rendered by Pakistan in the fight against terrorism and frustration over the Taliban and other groups continuing to operate from Pakistani soil.

'There can be no peace and stability unless...'

Clinton reminded Pakistanis that the only way forward in the relationship marred by deep mistrust over counter-terrorism efforts was to redouble efforts in the fight against terrorists.

She spoke of "vicious terrorists" having found sanctuaries on Pakistani soil and Afghan militants operating from safe havens in tribal areas and said it was Islamabad's responsibility to stop that from happening.

She added, "There can be no peace, stability, no democracy, no future for Pakistan unless the violent extremists are removed."

Clinton said she had been assured of "some very specific actions" which Pakistanis would take in coming weeks. She did not give any details.

According to ABC News of the US, as quoted by the Pakistani media, the US side demanded immediate action and intelligence sharing on four leading terror names -- Ayman Al-Zawahiri, Siraj Haqqani (operational commander of the Haqqani network), Ilyas Kashmiri and Atiya Abdel Rahman (Libyan operations chief of Al Qaeda, who was allegedly a key aide to bin Laden when he was hiding in Abbottabad).

'Somebody, somewhere, was providing some kind of support'

Dawn claimed that an American source confirmed the list and said the US softening on its position on the unilateral action was conditional. 'The message given to Pakistani leaders was loud and clear; you either cooperate with us on these four terrorists or we'll take care of them by ourselves.'

Dawn further reported: 'Something the sceptical secretary found reassuring was a rare acknowledgement made by the Pakistani side at the talks that Osama bin Laden enjoyed a support network as he spent his years near the army's elite training centre.

'Our counterparts in the (Pakistani) government were very forthcoming in saying that somebody, somewhere, was providing some kind of support, and they are carrying out an investigation and we have certainly offered to share whatever information we come across,' it said.

In return for the promised counter-terrorism cooperation, Clinton offered "respect for and addressing" Pakistan's concerns about the political settlement in Afghanistan. She did not elaborate, but said she was convinced that Pakistan had "legitimate" interests in the settlement of the Afghan conflict and its role was indispensable for the success of the reconciliation process.

'Conspiracy theories will not make problems disappear'

According to Dawn, Clinton was particularly critical of the growing anti-Americanism in Pakistan. Although she didn't explicitly say so, it was evident from her remarks that she thought a segment of the establishment was responsible for promoting it.

She said, "In solving its problems, Pakistan should understand that anti-Americanism and conspiracy theories will not make its problems disappear."

According to Dawn, her Pakistani interlocutors complained to her that statements by US officials, leaks to media and unilateral actions were reducing the space for cooperation.

Coinciding with her visit, US media has reported that Pakistan has closed down the three joint intelligence fusion cells in Quetta and Peshawar to which there was a reference in the WikiLeaks cables.