| « Back to article | Print this article |

'To counter naxals, concerns of weaker sections of society must be addressed'

Speaking at the Sardar Patel memorial lecture organised by Prasar Bharati, Union Minister Jairam Ramesh said India's left-wing extremism can be solved only if India's polity can rise above partisan political considerations and set aside old Centre versus state arguments to work concertedly to restore people's faith in the administration.

Excerpt of Jairam Ramesh's lecture on 'From Tirupati to Pashupati: Some Reflections on the Maoist Issue'.

The title comes from the popular image in the media that a "liberated" red corridor is sought to be created extending from Andhra Pradesh to Nepal and cutting across the very heart of India. This has been described by the prime minister to be India's most serious internal security challenge and by the home minister to be even graver than the problem of terrorism.

Armed communist insurgency is something that the nascent Indian nation-state - of which Sardar Patel was the home minister - confronted in Telangana even as the constituent assembly was debating the architecture of our republican democracy founded on adult suffrage and positive discrimination in favour of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. The modern-day Maoists see themselves as legatees of this uprising, which Sardar Patel dealt with firmly but sensitively.

The phenomenon of Naxal violence has been studied by official committees from time to time. I recall that in the early 1980s, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi sent a team headed by the-then member-secretary of the Planning Commission to conduct field-level studies of Naxal-affected areas in Bihar and Andhra Pradesh and recommend solutions both for the Centre and the States to adopt. The author of this report is, incidentally, now our prime minister.

The recommendations were many but the main point made was that urgent and long-festering socio-economic concerns of the weaker sections of society must be addressed meaningfully if the influence of Naxal groups is to be countered effectively.

Click NEXT to read further...

'Home minister's offer to Maoists is quite fair'

More recently, three years ago the Planning Commission published the report of its 17-member expert group on development challenges in extremist-affected areas. And what a group this was. It had all the people you would want for such an exercise, people who have spent a life time thinking, speaking, writing and working on this subject—people like Debu Bandopadhyay, S R Sankaran K Balagopal, B D Sharma, K B Saxena, Ram Dayal Munda, Dileep Singh Bhuria and Sukhadeo Thorat to name just eight of them. As was only to be expected, the report of this group was extraordinarily detailed.

It gave the historical, political, social and economic context to the issue, reviewed government efforts to deal with the problem and recommended a number of key policy and programme measures and changes to vastly and visibly reduce, if not totally eradicate, the effects of Left-wing extremism in different states.

Running into 95 pages, this report may lack the lyrical beauty and sheer poetry, misleading though it may be, of Arundhati Roy's now famous 33-page essay in Outlook magazine, but for sheer comprehensiveness and depth of analysis and for showing a practical way ahead it has no peers.

Please permit me to inject a personal note here. As a student of India's political dynamics I have always had an intellectual interest in this subject, but over the last seven years, my involvement has grown and has become increasingly more direct. First, since 2004 when I became a Member of Parliament from Andhra Pradesh, I have used my MPLADS funds mostly in Adilabad, Warangal and Khammam—three Naxal-affected districts--to strengthen women's self-help group organisations and reduce the trust deficit between tribal communities and the civil administration.

Second, between June 2009 and July 2011 as minister in charge of environment and forests it fell on me to bring about changes in forest policy and administration since this has been identified as a key factor in dealing with the issue of Naxal violence. Third, since July 2011 as minister in charge of rural development covering key programmes like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana, watershed management, drinking water supply, housing, social assistance and modernisation of land records, an opportunity has been afforded to me to address the development deficit in the Naxal-affected areas that the 17-member Planning Commission expert group so tellingly identified.

Before I go any further on the development route, I wish to pause and reflect on something that the Union Home Minister has so forcefully said on more than one occasion, quite in contrast to his predecessor, who described the Naxals as "our wayward and misguided younger brothers" (and I should add increasingly sisters) who have to be gently persuaded and cajoled to give up the cult of violence and wanton killings.

Both in Parliament and outside, the present home minister has said that on the basis of material gathered from captured left-wing extremist groups, it is unequivocally clear that their objective is the violent overthrow of the Indian state and that their basic ideology is a complete rejection of Parliamentary democracy as enshrined in our Constitution.

Knowing the home minister as I do, I can attest to the fact that he believes very much in the "developmentalist" approach, the strategy and approach advocated, for instance, by the expert committee of the Planning Commission to which I referred earlier. But he does raise a fundamental point that should not be brushed aside summarily.

Of course, the Indian state has confronted many groups in the past that reject its very basis and rationale. And in many cases, these very groups that have fought the might of the Indian state for years have finally come around and become a peaceful part of our polity. I might recall here that in the 2009 Lok Sabha elections, Kameshwar Baitha, a top Naxal leader, contested and won on a Jharkhand Mukti Morcha ticket from Palamau in Jharkhand. Some weeks back in Kolkata the Union home minister reiterated that the Centre is ready for unconditional talks with Maoists and all that it is demanding that they stop violence without necessarily giving up their ideology, surrendering their arms or even disbanding their militias and armies. I cannot think of a fairer offer than this.

Click NEXT to read further...

'Naxals using tribal areas, issues for tactical purposes'

It is my good fortune to have two outstanding IAS officers working with me now; both have had the misfortune of being abducted by the Naxals. One was kidnapped in 1987 in Rampachodavaram in East Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh along with S R Sankaran and kept captive for four days. The other was held hostage for nine days in Malkangiri district of Orissa.

Both the officers are very strong advocates of the S R Sankaran approach of development and sensitive governance in tribal areas. But in my continuing conversations with them, two things have emerged. One, the Naxals are exploiting the tribals and two, the tribals themselves want peace, not war. The Naxals are using the tribal areas and issues for their tactical purposes.

The terrain and the forests suit them for guerrilla warfare. They have spread their terror and ensured that the developmental activities are obstructed. The tribal cause, which the Naxals espouse, is only a mask to further their own agenda. The Malkangiri incident is a clear message from the tribals of the region that they want development and not Naxal terror.

What is clear is that we need a two-track approach--one that deals with the leadership of the Naxals, who wish to overthrow the Indian state and the other, which focuses on the concerns of the people they pretend/claim to serve. There is clearly a need to recognise tribal populations as victims--first of state apathy and discrimination and then of the Naxal agenda. My firm belief is that a complete revamp of administration and governance in tribal areas, especially in central and eastern India, is the pressing need of the hour. Andhra Pradesh has attempted to do this through its ITDA (Integrated Tribal Development Agency) model, but much more needs to be done. We must also come to grips with the sad reality that affirmative action programmes like reservations have had a very marginal impact on the welfare of the central and eastern Indian tribal communities.

The Union government has identified 60 districts in seven states that are affected by left-wing extremism. Of these, 15 are in Orissa, 14 in Jharkhand, 10 in Chattisgarh, 8 in Madhya Pradesh, 7 in Bihar, 2 each in Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh and one each in West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh. 18 more districts are being considered for inclusion.

States have said that the "block" and not the district should be the basic unit for identification and I quite agree with this demand. There are a few districts, for instance, Guntur in Andhra Pradesh and Raipur in Chattisgarh, which are not part of this 60 but where certain blocks are badly affected. I am hopeful that when we get into the XIIth Five Year Plan from April 2012, we would have made this change from the district to the block.

When you look at these 60 districts on a map of India, five characteristics stand out. I should, however, mention straightaway that the 7 districts of Bihar are an exception to these generalisations. Bihar has its own dynamics embedded in caste and land-related structures.

First, an overwhelming majority of these districts have substantial population of tribal communities. Second, an overwhelming majority of these districts have significant area under good quality forest cover. Third, a large number of these districts are rich in minerals like coal, bauxite and iron ore. Fourth, in a number of states, these districts are remote from the seat of power and have large administrative units.

Fifth, a large number of districts are located in tri-junction areas of different states.

Let me make a couple of observations based on personal experience on each of these characteristics. On the size of administrative units, recently on a visit to Chattisgarh I discovered that the size of some blocks (like Conta in Dantewada district and Orchha in Narayanpur district and Orgi in Surguja district) was equivalent to the size of some districts in some other states and indeed equivalent to the size of some other states themselves.

Click NEXT to read further...

'Need to empowering tribals, who are victims of state and naxals'

Given poor connectivity and infrastructure to begin with, this is a huge handicap to contend with by administrators. Rationalisation of administrative units is entirely within the domain and powers of state governments. The Chattisgarh government has very recently decided to create five more districts in the Naxal-affected regions of the state and this is a good step.

On the tri-junction nature of these districts, Debu Bandopadhyay, one of the key administrators responsible for land reforms in West Bengal in the seventies and early eighties, has an interesting story to tell. When I mentioned this dimension to him recently in Kolkata he recalled that this was very much part of Hare Krishna Konar's considerations while working out the strategy in the early 1960s before the CPM came to power in West Bengal.

I was told that Konarbabu focussed on three specific areas as epicentres for class struggles—Naxalbari, Jangalmahal and Hasnabad--all three of which are in tri-junction areas. Today the key tri-junction areas are Chattisgarh-Maharashtra-Andhra Pradesh, Orissa-Chattisgarh-Andhra Pradesh, Orissa-Jharkhand-Chattisgarh, Orissa-West Bengal-Jharkhand. The challenge is to quickly improve infrastructure—roads and bridges more specifically—that enables basic developmental activities to be carried out.

My own view is that there is no alternative to the Central government stepping in for financing and executing these tri-junction infrastructure works. It is not happening at the speed at which it is required.

Realising the need for smaller units accompanied by a broader pan-state approach to dealing with the administrative aspect is an important first step to deal with the problem. But the real challenge is how do you transform administration in tribal areas so as not only to give people a sense of participation and involvement but, more fundamentally, to preserve and protect their dignity"?

How do you prevent or address their continued victimisation, first by the state and now by the Naxals? Empowering the tribals, who are essentially victims, by giving access to basics, by giving them what is theirs by right and by securing their livelihoods is, to my mind, an absolute undiluted must. Here, issues related to land ownership and land alienation must receive over-riding priority.

On the minerals issue, the Union cabinet has very recently approved the repeal of the Mines and Minerals (Regulation and Development) Act, 1957 and its replacement by a new law. This new law will establish a District Mineral Foundation in each of the mineral-rich districts into which will flow every year an amount equal the royalty paid (for minerals other than coal) and equal to 26% of net profits as far as coal is concerned.

This works out to something like Rs 10,000 crore annually at present rates to be distributed across the mineral-rich districts which could each get close to Rs 180-200 crore per year. These additional resources are to be used for local infrastructure development and for the welfare of the communities impacted by mining activities. The new law also provides for the approval of local communities before mining concessions are granted and when mine closure plans are implemented.

On the forests dimension of the Naxal-affected districts, I took five major initiatives when I was at the MoE&F. First, state government-executed physical and social infrastructure works requiring less than 5 hectares each of forest land were exempted from the approval processes of the Forest Conservation Act, 1980 as also the need for compensatory afforestation.

Second, amendments were approved to Section 68 of the Indian Forest Act, 1927 that not only raise the monetary limits to which offences could be compounded but also ensure that local forest officials can lodge cases only after the written consent of the gram sabha. Third, a beginning was made in Menda-Lekha village of Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra to transfer control of the transit pass book for bamboo—the most important NTFP (non-timber forest produce)—from the forest department to the gram sabha.

Fourth, an expert review of the implementation of the Forest Rights Act, 2006 was initiated along with the Ministry of Tribal Affairs and specific reform measures identified including a sharper focus on the recognition and granting of community, as opposed to just individual rights.

Fifth, the idea of a Central minimum support price (MSP) for 12 major items of NTFP, coupled with the removal of all purchase monopolies, was taken up with the Planning Commission and the finance ministry. These initiatives must be taken forward. More than anything else, I firmly believe that a completely transformed forest administration lies at the very core of an effective anti-Naxal strategy.

Regarding the tribal nature of the Naxal-affected districts, much has been said about the pivotal role that the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (known popularly as PESA, 1996) can play in fulfilling the aspirations of people in a manner by which they are fully involved and empowered. However, even after fifteen years, the Act has yet to be translated into reality primarily because of the reluctance of the states and also because of the reluctance of the Centre to invoke its provisions to take on a more direct and active (and activist) role in Schedule V areas.

There continues to be considerable divergence of opinion on whether "consultations" with the gram sabha as envisaged in the legislation is adequate or whether there should, in fact, be "prior informed consent" before the start of development projects. Furthermore, I am convinced that implementing PESA in an environment where the local administration is dominated by disinterested and always-ready-to-leave non-tribal personnel will just not have any positive impacts.

The technical and organisational capacity of panchayati raj institutions has to be built up urgently.

One important administrative innovation introduced by the Central government in these 60 districts is to give untied funds to a troika comprising the Collector/District Magistrate, the Superintendent of Police and the District Forest Officer. In 2010/11, Rs 25 crore was released to each district and in 2011/12 another Rs 30 crore will be released. The idea is that the triumvirate representing the face of the Indian state as it were would be in a position to identify critical developmental works that could taken up and completed quickly so that the people begin to see the government in a completely new light.

These works cover ashram schools, anganwadi centres, drinking water schemes and roads. This has spurred unprecedented development activity in these districts and it is interesting to note that none of the works taken up so far have been the target of Naxal attacks. This initiative should continue on an expanded scale but the challenge will be to give a role to elected representatives and local elected institutions in the selection and execution of works without, of course, losing its essence—which is flexibility and speed of execution.

Click NEXT to read further...

'Establish paralegal assistance centres in naxal districts'

In my current ministerial assignment, I consider the PMGSY (Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana) to be the single-most important rural development intervention that can significantly transform the ground-level situation in the (left wing extremism) LWE-affected districts. This is not to minimise the importance of other programmes but the PMGSY stands apart. The first target of Naxals is roads, that is why PMGSY works are severely lagging in the LWE-affected districts.

Some innovations have been made to maximise the involvement of local contractors, for instance. But there have been frequent instances of these contractors being killed. Some degree of security cover by para-military agencies like the CRPF will be essential to expedite PMGSY works. But we have a long way to go.

There are 25 districts out of the 60 LWE-affected districts where the expenditure levels are lower than the overall national average. And within these 25, there is a core of 10 districts where expenditure levels are lower than the average for the LWE-districts themselves. These to me appear to be the districts where Naxal activity is most intense.

These ten districts are Bijaipur, Narayanpur and Dantewada in Chattisgarh, Gadchiroli in Maharashtra, Khammam in Andhra Pradesh, Lohardaga, Gumla, Latehar and Simdega in Jharkhand and Malkangiri in Orissa. It is here that we need the synergy between the security forces and implementing agencies on the ground in order to speed up connectivity without which nothing else worthwhile is really possible.

We have estimated that in order to complete all PMGSY works covering habitations with a population of 250 to 500 in these 60 LWE-affected districts about Rs 15,000 crore will be needed. Another Rs 19,000 crore will be needed to complete road connectivity to habitations with population less than 250.

In addition, we will need additional funds to complete small and minor bridges (unlinked with PMGSY roads per se) which have an importance of their own in these LWE-affected districts. I am optimistic that these resources will be forthcoming—the challenge really will be to ensure project completion in the next three-four years at most. We need a renewed sense of urgency and a "get it done" attitude. And we are battling huge odds. One small bridge—the 1 km Gurupriya bridge—that is crucial to fighting Naxalism in Malkangiri district in Orissa has been talked about for almost three decades and it still remains to be constructed.

Along with PMGSY, I consider interventions to ensure the speedy settlement of land-related disputes to be high priority in the LWE-affected districts. In many places, the ability of the Naxal cadres to mete out "instant justice" has given them a foothold and acceptance amongst the people at large. Here I recall my personal experience some years back. When I first went to Adilabad in 2004, I met a feisty Gond lady called Mankubai whose land had been usurped by outsiders and she had been fighting her case with the government and with the judiciary for over two decades. I immediately mobilised some young lawyers who, working under the aegis of the state government's Society for the Elimination of Rural Poverty (SERP), were able to get Mankubai's land restored to her.

That experience is still fresh in my memory and that is why I am now proposing to support the establishment of paralegal assistance centres in all the LWE-affected districts. These centres would document all cases of land alienation and work for the restoration of lands to their rightful owners, mostly tribals.

Click NEXT to read further...

'Para-military action should not be driving force in Naxal-affected areas'

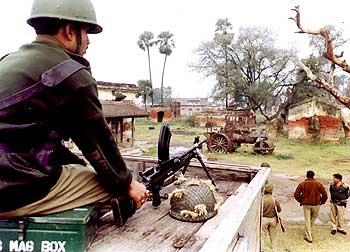

The might of the Indian state is in the Naxal-affected areas. 71 battalions of central para-military forces, amounting to some 71,000 personnel, have been deployed. They have a vital role to play in backing the state police and in developmental activities. The Collector of LWE-affected Balaghat in Madhya Pradesh told me recently how the presence and approach of the CRPF in the area had a considerable psychological impact enabling villagers to come out in large numbers to seek employment under Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act.

But let us be clear, para-military and police action cannot and should not be the driving force. The driving force has necessarily to be development and addressing the daily concerns of the people, of people who have every reason to feel alienated. Massive reform of the police and the forest administration at the cutting edge is the need of the hour.

A more humane policy of land acquisition with focus on effective rehabilitation and resettlement (R&R) is the need of the hour. I think it was Walter Fernandes the noted sociologist who estimated that over 50 million people in central and eastern India have been displaced over the past five decades due to developmental projects. R&R for very large numbers of people has yet to be completed. Worse, there are large numbers of tribals who have been subjected to repeated displacements.

It is not the Naxals who have created the ground conditions ripe for the acceptance of their ideology—it is the singular failure of successive governments both in states and governments to protect the dignity and the Constitutional rights of the poor and the disadvantaged that has created a fertile breeding ground for violence and given the Naxals space to speak the language of social welfare but in reality use that as a cloak to construct their guerrilla bases and recruit most tragically women and children in large numbers.

So where do we go from here? Let us not underestimate the seriousness of the threat we are faced with. I, for one, do not believe that a "developmentalist" strategy alone, so eloquently advocated by the Planning Commission's Expert Group, will do. I also do not believe that a strategy based on the primacy of para-military and police action will yield long-term results. The two must go hand-in-hand deriving strength from each other.

We are combating not just a destructive ideology but are also confronted with the wages of our own insensitivity and neglect, especially in so far as the central Indian tribal population is concerned. Simply put, we need to rise above partisan political considerations and set aside old Centre versus state arguments and work concertedly to restore people's faith in the administration to be fair and just, to be prompt and caring, to be prepared to redress the injustices of the past, and to be both responsible and responsive in future. Only then will the tide of Naxalism be stemmed.