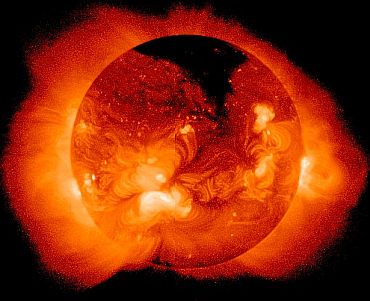

One of the longstanding mysteries in solar physics is why the Sun's outer atmosphere, or corona, is millions of degrees hotter than its surface.

Now, scientists claim to have finally solved the mystery after they discovered a major source of hot gas that replenishes the corona -- jets of plasma shooting up from just above the Sun's surface, the 'Science' journal reported.

Scott McIntosh of the National Centre for Atmospheric Research in Colorado, a member of an international team, which carried out the NASA-supported research, said: "It's always been quite a puzzle to figure out why the Sun's atmosphere is hotter than its surface.

"By identifying that these jets insert heated plasma into the Sun's outer atmosphere, we can gain a much greater understanding of that region and possibly improve our knowledge of the Sun's subtle influence on the Earth's upper atmosphere."

Click on NEXT to read further...

Team member Rich Behnke of the National Science Foundation, which funded the research, said: "These observations are a significant step in understanding observed temperatures in the solar corona. They provide new insight about the energy output of the Sun and other stars. The results are also a great example of the power of collaboration among university, private industry and government scientists and organisations."

In fact, for its research, the team focused on jets of plasma known as spicules, which are fountains of plasma propelled upward from near the surface of the Sun into the outer atmosphere.

For decades, researchers believed spicules could send heat into the corona. However, following observational research in the 1980s, it was found that spicule plasma did not reach coronal temperatures, and so the theory largely fell out of vogue.

"Heating of spicules to millions of degrees has never been directly observed, so their role in coronal heating had been dismissed as unlikely," said Bart De Pontieu, the lead scientist and a solar physicist at Lockheed Martin's Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory.

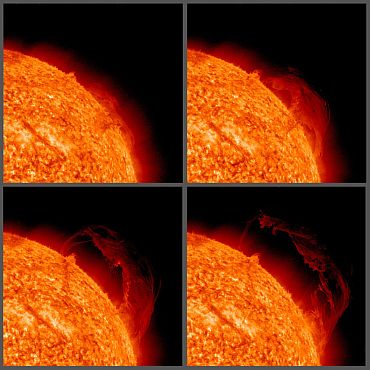

In 2007, De Pontieu, McIntosh, and their colleagues identified a new class of spicules that moved much faster and were shorter-lived than the traditional spicules. These "Type II" spicules shoot upward at high speeds, often in excess of 100 kilometers per second, before disappearing.

The rapid disappearance of these jets suggested that the plasma they carried might get very hot, but direct observational evidence of this process was missing.

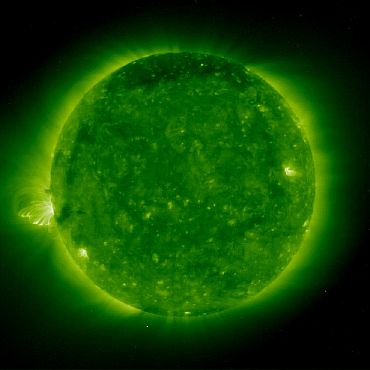

In its latest research, the team used new observations from the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly on NASA's recently launched Solar Dynamics Observatory and NASA's Focal Plane Package for the Solar Optical Telescope on the Japanese Hinode satellite to test their hypothesis.

"The high spatial and temporal resolution of the newer instruments was crucial in revealing this previously hidden coronal mass supply.

"Our observations reveal, for the first time, the one-to-one connection between plasma that is heated to millions of degrees and the spicules that insert this plasma into the corona," McIntosh said.