| « Back to article | Print this article |

Musings of a first-time Indian voter in America

Murali Kamma compares the masala Indian election circus to America's more staid presidential race

Just when I thought I was done with primaries, turns out I have to worry about priming. But first, I have the important task of choosing the right bumper sticker. After all, I became a citizen in 2011, and this year I'll be voting for the first time -- anywhere.

The other day, coincidentally, I received a bunch of suggestions by e-mail. I liked them and would have loved to pick one freely -- but then again, I'm also fond of my car and hope to keep it a little longer. While most can be excluded, unless somebody comes up with bumper sticker insurance, a few seemed promising.

"Voting is like driving a car," reads the first one in big letters. And below that, in smaller letters, we have: "Choose (R) to move backward. Choose (D) to move forward." Now this is by no means subtle. But isn't the point of a bumper sticker to make your preference loudly clear?

"Politicians, like diapers, should be changed often. And for the same reason." That was funny and apt, but I vetoed it on the grounds of taste.

"I'd vote for a Republican, but I'm allergic to nuts," said another one, tempting me. But I dropped it like a hot campaign button. Or perhaps like a hot-button issue.

I didn't want to offend my wonderful, helpful, GOP-supporting neighbors -- although I'm sure they'd have loved this one, "I'd rather be a conservative nut job than a liberal with no nuts and no job!"

Ultimately, I went with a crisper version of the first one. Although it's obvious which way I lean, I think of myself as an independent voter rather than a party ideologue. So, now the two lines read: "You want to take the country back. We want to take it forward!"

Am I a flip-flopper? Because, as some would point out, both Democrats and Republicans think they are moving forward while their opponents are going in the wrong direction. Given my renewed enthusiasm for politics, I regret that I couldn't vote in India.

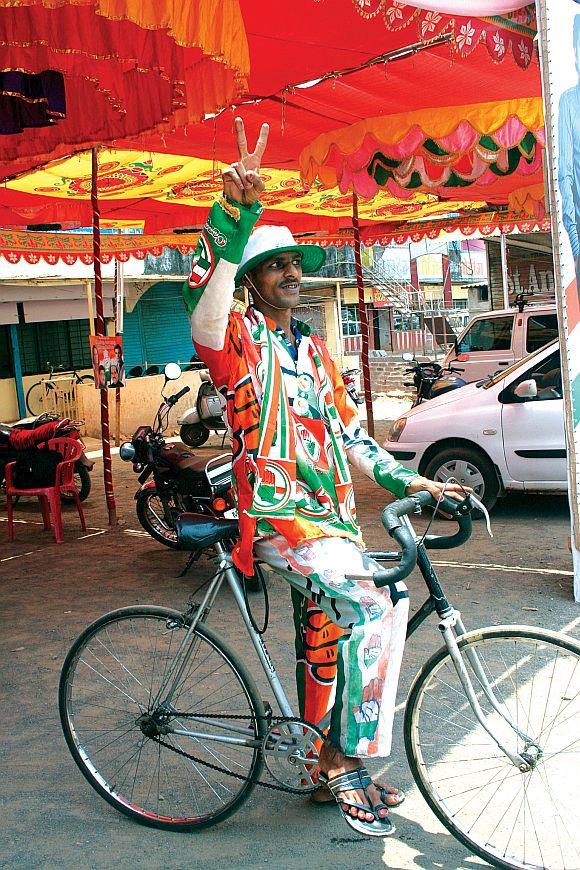

The US and India may be the world's largest democracies, but their political systems are quite different, as are the election seasons. Here there's no tamasha on the streets, no canvassers with loudspeakers, no riot of color or colorful riot, no booth-capturing and ballot-stuffing (in the era before electronic voting machines), no music and dancing to the accompaniment of celebratory fireworks.

It's all too serious, as if the fate of the nation is hanging in balance. It is, in a way. All the same, the voter turnout here, especially among less affluent groups, is nothing to be proud of -- while in India, it is much higher, where you have heart-warming scenes of powerless people standing in long lines, dressed in their best clothes, patiently waiting to exercise their power at the ballot box.

Click NEXT to read further

Musings of a first-time Indian voter in America

Of course, to restate the critic Ashis Nandy's point, psephocracy is not the same as democracy. The Indian election season is more raucous for another reason: the parliamentary system.

The list of parties, with bewildering abbreviations and ever-shifting alliances, is so long that one needs a checklist to keep track. In India's 2009 general election, we had the Nationalist Congress Party, the Indian National Congress, Bharatiya Janata Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, Communist party of India-Marxist and Rashtriya Janata Dal.

And these were just the national parties. There were also 39 regional parties, with an alphabet soup of abbreviations, not to mention coalition parties like the United Progressive Alliance and the National Democratic Alliance. In case you think this is a fairly recent trend, India's first general election in 1951 had no less than 53 parties.

America's two-party domination, in comparison, is staid -- and stable. In the 2008 election, one only had to know about the Democratic and Republican parties. The other three parties (Libertarian, Green and Constitution) played a negligible role.

Undeniably, the era of coalitions in India has created problems, even as it mitigated some of the excesses of dynastic politics. But though the multiparty system is not going away, the Americanisation of India in recent years raises a question.

As India leaves its British legacy behind, should it also ditch the parliamentary system and adopt the US model? Not a few think it would be a good idea. I don't. Whatever its flaws, the parliamentary system is a good fit for multilingual, multicultural India. The question is merely hypothetical, in any case.

It's like asking whether Indians should switch from driving on the left side to the right, although some would see it as a moot point. Unlike the British or Americans, they'd argue, Indians actually drive in the middle of the road!

Whatever. Or should I say WYSIATI? Coined by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, psychologist and bestselling author of Thinking, Fast and Slow, it stands for "What you see is all there is."

In other words, we tend to believe that the information available to us now is complete, allowing us to make decisions. Big mistake, not least during the political season, because of what I call WAASWIS ("We are all suckers when it's spin").

Which brings me to priming. 'Studies of priming effects have yielded discoveries that threaten our self-image as conscious and autonomous authors of our judgments and our choices,' writes Kahneman.

'For instance, most of us think of voting as a deliberate act that reflects our values and our assessments of policies and is not influenced by irrelevancies. Our vote should not be affected by the location of the polling station, for example, but it is.'

And it's also unfortunately true that no matter how hard we try, we can never be entirely free of our cognitive illusions. So who knows what I'll end up doing on November 6!

Murali Kamma is an Atlanta-based writer and editor

TOP photo features of the week

Click on MORE to see another set of PHOTO features...