Photographs: Rajesh Karkera

The events of 26/11 last year have inadvertently, inconvertibly linked the lives of four people working on Nowroji Furdunji Road (named after a 19th century Parsi reformer) in Colaba, south Mumbai -- Bharat Waghela, Sabuddin Khan, Santosh Bireram Kanojia, Vasant Gohil.

Waghela and Kanojia also live on this street. Waghela runs a pharmacy. Kanojia, who hails from Dehjsuri, near Jaunpur, Uttar Pradesh, is a dhobhi and rents a workshop here, earning Rs 6,000 to Rs 7,000 a month. Khan was a tailor attached to Khubsons clothing and fabric shop in Colaba. So is Gohil who runs a handkerchief-sized shop with his brother Dev.

This narrow lane, bustling with foreign tourists who frequent its cyber cafes, restaurants and shops, connects Colaba Causeway with B K B Behram Marg onto which the rear entrance of the Taj Mahal Palace and Tower opens. On its corner is the ever, and even more, popular Leopold Cafe.

When the shooting began at Leopold Cafe it took Waghela, Kanojia, Gohil, and probably Khan, just 30 seconds to realise that what they thought was simply a round of harmless firecrackers exploding was actually a shoot out.

Khan and Kanojia, standing in the doorway of the facing building, Causeway Hospital, furtively peeping out, paid hugely for that moment of curiosity. Waghela standing just behind them escaped unharmed.

One of the terrorist duo, in a split second, suddenly swung away a sharp 180 degrees -- from shooting into the cafe through a side door and fired at the bystanders gathered in the lane and even up at the windows of the building.

Khan died on the spot of a fatal head injury. Kanojia fell to the ground severely injured in the right arm, unconscious, but fortunately alive. Had their positions in the doorway by some odd fate been reversed Kanojia would not have lived to tell his tale: "There was a noise in the street. I thought it was firecrackers and I went out to see. At that very second the terrorist turned and shot us. Khan collapsed. He was dead. His head was split open. Then I was hit. I never really had time to even see their faces. I only regained consciousness in the hospital after the operation to remove the bullet."

"The doctors were very good. My family (his wife and three children live in the village) only got to know later that I was injured. When I went home they published my story in the local Jaunpur paper (he shows a laminated article from Jaunpur Jagran)."

"Now (as a lesson learnt) I don't go out to see something (a noise, something happening). My arm has healed (he shows a long scar and his arm is able to twist abnormally backwards because of the wound) but I can only iron half an hour at a time and need a break. I have hired an assistant who helps me. For me that was a hawa or whirlwind (the events of 26/11) and it went (the way it came)."

The clutching, numbing fear in his heart has now passed

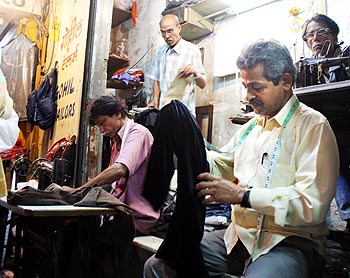

Image: Vasant Gohil in his open air tailoring stall next to Leopold Cafe.Photographs: Uttam Ghosh

A few yards away Gohil, who sits with his back to Leopold Cafe, in his open air tailoring stall, was still a little more lucky, but miraculously so.

"It was 9.30. I was just cleaning up. Suddenly the sound of crackers came from within Leopold. I thought it had to do with the India-England ODI going on (in Cuttack). Then everyone started running and I ran in too."

"A bullet whizzed right by my head and one grazed my ankle. We saw Sabu fall. He died right there. My mobile phone got stuck in the shop and everyone was calling to see if I was safe and I could not answer."

After a while Gohil remembers that the people/public still cautiously peeking out and watching said the terrorists had gone ahead down the dark lane towards the Taj, even as they threw grenades and continued to fire from their AK-47s.

When he got through to his crazily anxious family, finally, on someone else's phone, they told him not to come home. He lives near R K Studio, a photographic studio that faces Hormusji Street on which Nariman House is located in Colaba and it was under attack too.

So Gohil set out past the Electric House to a friend's kharkhana (workshop) at the Oval, near Churchgate station and spent the night there.

"Takdeer ki baat hai (It was a matter of luck)."

For three or four months he lived with a clutching, numbing fear in his heart. But that has now passed.

'People get their photos taken under the bullet marks at Leopold Cafe'

Image: Bharat Waghela at his medicine store. He lost his brother in the shootout.Photographs: Rajesh Karkera

"I was at home watching the match that evening. When the firing sound came I looked out," he says. "I saw flashes of lightning. Then the sound of firing. Lightning again. I ran down with my nephew and cousin to see. I could see light flashing in the window of Leopold. And I saw the man who was standing there and shooting."

"He was wearing dark clothes. Later when I saw them moving ahead I could see that they had knapsacks and caps worn ulta or backwards on their heads. He started shooting at us. Sabu Uncle was hit and he was lying in blood. You could tell he was dead. I ducked and then I ran in and up to the house and told them to stay away from the windows because they were shooting up too."

What Waghela did not realise was that in those few minutes his elder brother Subhash, who was manning Chamunda Chemist, had been shot. Customers, including a few tourists and staff, were inside the shop and Subhash had dashed out to roll down the shutter. He received a shot on the side of his stomach and on his arm.

Waghela peeped out of the window after the terrorists moved ahead and realised his brother had been shot. He sprinted downstairs and across the road and carefully pulled his brother into a side alley waiting for the terrorists to disappear.

At first Waghela thought his brother's injuries were minor till he saw the stomach wound and began scrambling for a taxi to take him to a hospital. Luckily a police inspector came by in a car and turned his car over to them.

Waghela rushed his brother to the Pophale Nursing Home, opposite Regal Cinema. But the nursing home said it was a police case and would not take him in.

"We wasted 10, 15 minutes like that and managed to get him a a taxi and take him to St Georges's," he recalls with quiet anger.

At the hospital, doctors operated on Subhash Waghela immediately. Ten to 15 operations were going on at the same time. "At 4 or 4.30 am they told us he was okay and that you can go in and see him. But there was someone else recovering in the theatre. And there was a body outside. It was my brother," recalls Waghela tearfully. "Later they said he had died of blood loss and no BP."

Bitterness wells up swiftly when he recalls his brother's last moments and the events after that. He does not know if his brother died because in the melee he did not receive the treatment he needed or that it had been impossible finally for the doctors to save him.

He feels that the "crores of rupees" spent on Ajmal Amir Kasab's trial could have been allocated to some of the desperately poor victims.

Waghela also feels livid at the way the public remembers 26/11. "People just don't care," he says with angry emphasis. "They treat the places where the firings occurred like Jallianwalla Bagh (in Amritsar, Punjab, where 379 people died when General Reginald Dwyer ordered his men to fire at a peaceful public gathering in 1919), like a historical landmark. They sit down in Leopold Cafe at the table under the bullet mark and get themselves photographed."

"I have to take my relatives to see Leopold when they visit. Do you know that the day after the attack was over five lakhs (500,000) of people were roaming this area, fully dressed like they were going to a party or a wedding?!"

article