Photographs: Danish Ismail/Reuters

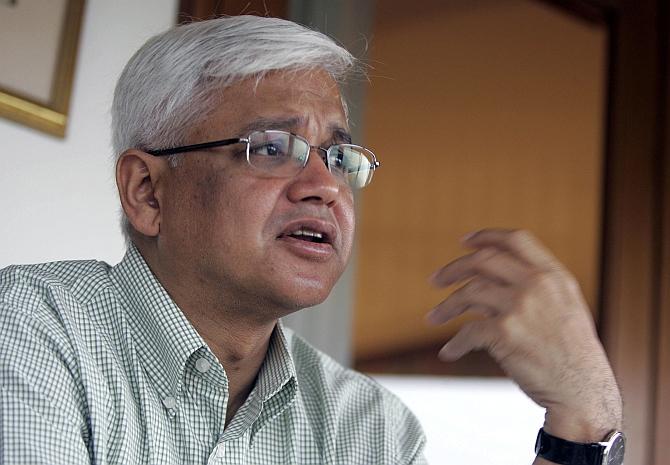

After Amartya Sen, yet another noted intellectual has come out strongly against Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi. Acclaimed author and Padma Shri awardee Amitav Ghosh has said that for him Modi remains someone culpable for the Gujarat riots of 2002 and for someone like him to become prime minister would be deeply destabilising for India. In an exclusive interview to CNN-IBN’s Deputy Editor Sagarika Ghose, he also said that the politics of Hindu nationalism is destroying Hindu religion.

About 25 years of The Shadow Lines

You know I really don't know but you are absolutely right, I do get this response from many readers; many people say to me there is something about The Shadow Lines that makes its way under your skin.

I think it is because you know it rose out of a great sense of inner turmoil inside me and at a time in my life when the country just seemed to be on the verge of some sort of really cataclysmic kind of ungluing if you like, it was something which haunted me. I think all of that went into the book.

On communal riots becoming permanent feature of India

The first thing to notice I would say is that it is not just about Hindus and Muslims. These riots have also happened in 1984 in relation to Sikhs, we have seen similar sort of events taking place in Assam involving the Bodos and other sorts of ethnic communities.

So it is not just Hindus and Muslims I would say. I think this book came very directly out of my experiences in 1984 when I was living and working in Delhi.

I am sure you will remember those days in November 1984 soon after Mrs (Indira) Gandhi’s assassination when this whole city sort of erupted in a way that to this day it defies belief. When you looked at the skyline of Delhi everywhere you looked there were towers of flame and smoke.

I think it is a sight none of us who saw it would ever forget. At that time I joined a group of activists who were trying to do peace march. I remember it is just absolutely engraved in my memory. How we walked through Greater Kailash and all these areas. All around us were these absolutely medieval scenes.

People with swords and spears, guarding their houses. That was one thing which was happening all across India there were these massacres in Assam. There were uprisings in various places. It was like V S Naipaul famously said -- a million mutinies. It is completely engraved in my memory

...

On role of rumours in spreading riots

Image: Soldiers detain two men for questioning during a curfew in Muzaffarnagar. About 50 people have died in in the communal violencePhotographs: Stringer/Reuters

What happened in Muzaffarnagar is appalling and really shocking, especially because of police inaction, their failure to discharge duties. All of that is totally shocking. But it’s important to remember how different this riot is from what we actually experienced in 1980s and 90s.

It’s important to remember that we had 20 yrs without a major riot. That is a huge difference in the history of India. In the 1980s or 90s if something like Muzaffarnagar had happened, it would have repercussions all across the subcontinent, and that hasn't happened.

So let’s remember the pluses as well as the minuses. This riot didn't serve that incendiary function of setting off imitative riots across the country.

I can absolutely assure you that in 80s and the 90s if such an event would have occurred it would have had repercussions elsewhere and that is what The Shadow Lines is about, how something happens in Hazratbal, it immediately has repercussions in Dhaka, in Kolkata, in Mumbai, across the country.”

On forces behind religious nationalism wrecking havoc

Absolutely, I think they would wreak much more havoc if they could. What is surprising is that in these 20 yrs they have not been able to wreak as much havoc as they would like.

There again we have to be very grateful for the fact that in these last 18-20 yrs there has been relative peace. People have got on with their work. I think at the end of the day what people really want is security and stability.

On rise of Hindu nationalism cause of worry

Image: Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra ModiVery much. Absolutely. In a sense what is most worrying to me about it, is that it is taking away the traditions that I knew. It is the tradition that I grew up in. The way the riots happened, the way that Hinduism is projected often by Hindu nationalists. It’s completely unlike what I was taught, and the religion I learnt, through practice. I come from a family which was very observant.

I am not personally observant at all but my family was very observant. I have been on every single pilgrimage in India -- Badrinath, Kedarnath. It is horrifying to see what has happened there. I think in a sense it is to me what is most horrifying about this Hindu nationalism is that it has transformed faith into politics. I see no genuine love for spiritual attainment. In fact it’s the opposite.

One of the greatest traditions in Hinduism is bhakti, love. But now there seems to be so little of that, even as something remembered within this kind of political movement

On Modi becoming prime minister

I think what happened in Gujarat in 2002 is absolutely, it was a defining moment. It was horrifying to see what happened. It was one of the moments again when the whole world looked on and was completely appalled and I was completely appalled by what happened there.

How much of that responsibility devolves on Modi is something to be decided by the courts rather than you and me. But there is certainly no doubt that it happened on his watch and in that sense he is in some sense responsible. And in as much as it happened, these were murders.

He is also culpable. For someone with that past to occupy the highest position in this land would be, I think deeply destabilising.”

Will Modi get your vote?

No, Not at all.

...

On identity politics

I think this focus on identity is not only untrue but also it is deeply destructive. It creates a kind of narcissistic culture where everybody is focused not on collective idea of public good but upon issues of pride or boosting their own pride or issues of self-esteem. I think it is a catastrophic thing.

This kind of what you could call political narcissism has happened at this particular moment, when we not just as a country, but we as a species really face a species level threat from climate change. For me what is most worrying thing about India but also far beyond India, about most democratic societies around the world is that, that we are not confronting the single most important challenge that confronts the entire planet.

For me as a Bengali, certainly for someone who has spent a lot of time in the Sundarbans, you can see that the threat is not a deferred threat. It is not going to happen 20 or 30 or 40 years from now. It is happening today. We see how entire islands in the Sundarbans are going under water. We see how salt water is invading the land.

On India as a nation state

I feel that there are many ways in which the idea of nation really distorts our identity. At the same time building a nation as an institution and building an institution is an important thing. There is a sense in which what our phobias have built in India is an important thing.

It’s very different from what exists in other parts of Indian subcontinent. The very fact that we have a sort of pluralism embedded in our constitution makes it something exemplary and that’s what has made India possible really. That’s what has made our kind of co-existence possible.

If we lose that pluralism we are finished. It is not just Pakistan one can see this in. Look at Sri Lanka, the moment Sri Lanka started embedding Buddhism as the dominant religion, the country was torn apart. It became, in a journalist’s famous words -- the Lebanon of South Asia.

The single most important thing in our constitution is just pluralism. If we don’t preserve this tradition, we will be finished.

...

On creative freedom being in danger

The space for freedom in India has really shrunk to a great deal. I would go beyond that, it’s not just India, it’s across the world. We are facing a moment, when the threats to creative freedom of expression have changed. They come now from a different source. Until the 1940s and 1950s the main threat to freedom of creative expression was the oppressive state.

But now it’s more like the non-state actors, political parties, extremist groups and corporations. Corporations increasingly play a very large part in trying to shut down the freedoms of expression. How are we going to respond to this?

Clearly the old ways in which we responded to it, through organisations, collective roots; all organisations were geared to address issues relating to the state and to the law. But how do we deal with this new kind of threat which is much more diffused.

On Delhi as a different city that that of 1980s

Delhi is one place where the state is able to defend freedom of speech to some degree. I think it's the only city in India today perhaps where some space for free expression exists. In Kolakata, in Mumbai, in other parts of India that space does not exist.

Freedom vs security

This has essentially been the case in US since 9/11. To me to watch the way US has evolved, it is profoundly instructive. It is really hard to imagine that in a country such as the United States they would actually suspend Habeas Corpus and can keep it in suspension with something like the Patriot Act which allows a degree of surveillance, a degree of intrusion into people's lives.

If you look at the surveillance regime in US; in fact it's the case just as in Iraq, where the security comes above freedom. People everywhere make the same choice.”

...

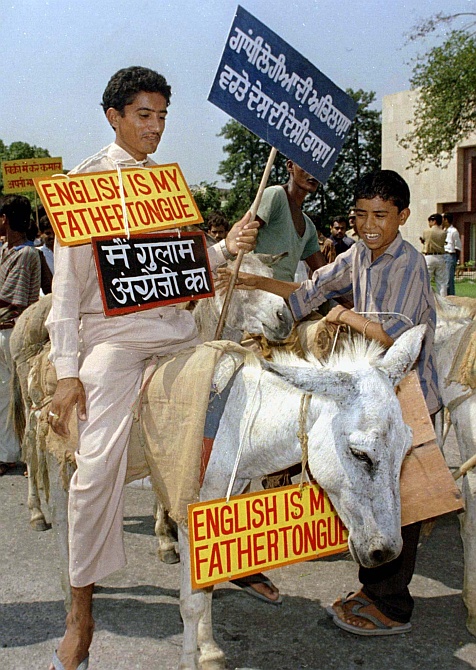

On language hegemony in India

Image: A protestor sits atop a donkey during a demonstration in support of the Indian languages and against the domination of EnglishPhotographs: Reuters

Everybody today is so desperate to learn English, because it helps them with career, access to the world. This is the case across the world as well. English has become so hegemonic across the world. It does play this dampening effect to some extent. There are also some positive developments in terms of linguistics in India today.

For instance the emergence of Bhojpuri film is a wonderful thing. Now Bhojpuri is emerging as a language, claiming its place. There are much more translations than what used to be before.

About the narrator in The Shadow Lines

I was reading Marcel Proust those days. Proust had a great effect on The Shadow Lines. The narrator of the book Remembrance of Things Past is nameless. When you have a nameless narrator that narrator becomes every man or woman. That's one of the reasons why it gets under the skin of the people.

About the Indian writers in English

One of the things that makes me so glad about the new India, there are many things to be depressed about, but few things to be glad about. You go to any bookshops and you will see shelf after shelf filled with books of young writers. Many of these writers are absolutely wonderful. I really enjoyed Chetan Bhagat's first book. I think it was a delightful book. I think he is a very talented writer. He has taken his work in a certain direction, but the talent certainly was there.”

What depresses about today's India

The lop-sided development. This resource extraction is killing so many parts of the country. The Supreme Court judgment on Niyamgiri is something to be proud of. Yet this resource extraction is continuing in many parts of the country, in a way that is ecologically dooming the future of the country.

We are extracting all resources with no thought for future.

article