| « Back to article | Print this article |

'If 55,000 soldiers had just held hands, the highway would have been cleared'

On November 29, after 121 days, the economic blockade and counter blockade of Manipur – by two 'rival' tribal groups, the first one lasting from midnight July 31 to October 31, and the second from August 21 to November 29 – came to a temporary end.

Sumit Bhattacharya travelled to the affected areas to understand how in a state where there are 55,000 soldiers who can under the law shoot you on mere suspicion and where even the police carry AK47s, 2.7 million people can be held to ransom over the proposed division of a district.

Read Part 2 of the series on Manipur: Manipur: The land of No Bollywood for 11 years

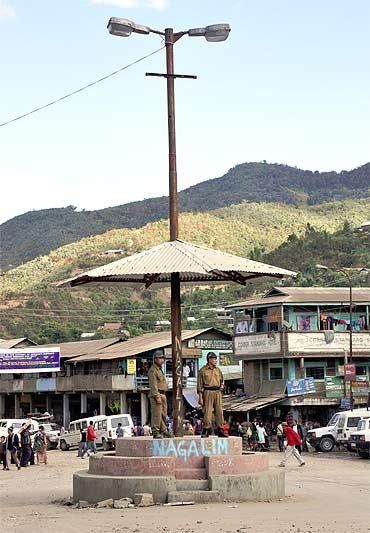

The two traffic policemen standing in the main square at the Senapati district headquarters are probably the only unarmed cops you will see in Manipur.

The word painted on the lamppost-turned-police outpost is 'Nagalim' -- the 'homeland' the Naga tribals dream of, and for which militant groups like the outlawed Nationalist Socialist Council of Nagaland have waged war with India for decades.

'Nagalim' is supposed to include Nagaland, and Naga-inhabited parts of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and Manipur. There is a ceasefire on between India and the Naga militants, or at least a major faction of them, for the last 14 years.

This is National Highway 39, which connects Manipur with Nagaland in the north, and which is one of the two 'highways' connecting Manipur to mainland India -- the only ways to access the India-Myanmar border state without flying in.

This so-called highway -- there are better roads even in the interior Himalayas -- was the theatre of an 'economic blockade' and a counter economic blockade, running concurrently for a large period of time, of the state of Manipur for 121 days.

At different parts of this road, a lifeline for most Manipuris who live in the valley, trucks were burnt, supplies stopped, vehicles searched for commercial goods -- like cooking gas cylinders, fuel, etc -- being carried into the valley of Imphal, the capital of Manipur.

The Kuki tribals, who want a separate district called Sadar Hills carved out of Senapati district, lifted their blockade when the state government signed an agreement with them agreeing to their demand.

The Naga tribals lifted theirs saying India's home ministry had assured them that there will be no redrawing of districts without Naga consent.

This, in a state where there are 55,000 soldiers. This, on a road where often you see convoys of VIPs with machine gun-mounted Gypsies manned by jawans in fatigues and bandanaas and on-mission commandos that remind you of scenes from Hollywood movies about Vietnam.

This, in a state with the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, which gives soldiers the legal right to shoot on mere suspicion.

"Please understand," says a top government official on condition of anonymity, when reminded that people have been shot when they blocked an intra-state highway like the Mumbai-Pune Expressway. "Here it is different. Here if we use force, it will be like we are using force against Kukis, or Nagas, and it can flare up into an ethnic conflict."

"What nonsense," says human rights activist Babloo Loitongbam. "If 55,000 soldiers had just held hands, the highway would have been cleared."

Welcome to Manipur -- a state scarred by history and geography, and bleeding from politics.

'If you want to kiss a girl and the girl objects, you call a bandh'

"Manipur is OK," declares a poster for the Sangai Festival -- the state tourism department's annual extravaganza to showcase the state's many vibrant cultures -- in Imphal.

In January, New Delhi decided that foreign tourists will no longer need the Protected Area Permit to enter Nagaland, Mizoram and Manipur. Except those from China, Afghanistan and Bangladesh, who will still need the Indian home ministry's prior approval. This is a one-year experiment.

Manipur has rare flora and fauna like the state animal Sangai. An endangered species, the Sangai or Manipur brow-antlered deer is only found on the banks of the Loktak, India's largest freshwater lake.

The state is a big valley surrounded by hills. The airport reminds you of Dehradun a bit. Only prettier. Its capital's streets are dustbowls.

Two days before the economic blockade is lifted, it's packed house at the Sangai Festival, at the gate of which a bomb will go off three days later.

It will leave India with yet another ghastly image: A police officer speaking to a rickshaw driver whose lower half has been blown away by the bomb he was unknowingly made to carry to the festival for Rs 20. The rickshaw driver will die in hospital, after telling the police that the bomb was given to him by a man who identified himself as a militant.

"Use your head," the same police officer will tell you. "Will you identify yourself if you're planting a bomb?"

But for now, all is fine. VIPs -- government officials, top cops, MLAs of all hues and ranks -- and police commandos with stenguns and AK47s are everywhere.

Food stalls are filled. Performances of a local theatre form in which men dress up as women have big crowds in front. Cultural performances in the open air auditorium are met with whistles.

A six-year-old girl is dancing the Kabui tribal dance. Had he been there, Maharashtra Home Minister R R Patil would have been very angry; many people including children walk up to the stage and shower currency notes on the little dancer.

Outside in the streets, there is a huge traffic jam leading to the festival venue, though petrol is being sold in the black market at about double the price of Rs 64. At the peak of the blockades, it touched Rs 200 in the black market and images of huge lines for petrol made it to national television.

On key roads, such as the one near the Kangla Fort -- seat of the erstwhile Manipuri king and former home to the Assam Rifles -- you can see road dividers being given fresh coats of paint. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and Sonia Gandhi are due soon.

As another top government official says, "Everything is on."

A four-day bandh is also on. To protest the burning of the huts of fisherfolk on the banks of the Loktak.

"We are used to it (bandhs and blockades)," says an Imphal resident, government employee and mother, dripping sarcasm. "We are a very adjusting people."

"Economic blockade, followed by counter blockade, followed by total bandh," quips Rewben Mashangva about the situation in Manipur. He is a celebrated Naga folk-blues singer -- a documentary film based on his life, Songs of Mashangva, won the 58th National Award for Ethnography.

"If you want to kiss a girl and the girl objects, you call a bandh," he adds, breaking into peals of laughter.

"Arre yaar, in Imphal, no bandh," says another long-time Imphal resident.

There are stories you hear of the police enforcing the bandh, and of the few shop owners who stay open -- and do brisk business -- being made to pay for it.

Fault lines of history in a beautiful state

Manipur -- part of the northeast's Seven Sisters, along with Mizoram, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Assam, Tripura and Arunachal Pradesh -- is deeply divided along ethnic lines. It's a burden of history and geography.

The British divided Manipur into the valley ruled by the Hindu king and the hills -- turned Christian by missionaries -- ruled by a Britisher, the president of the Manipur State Durbar. The Indian Constitution followed the same pattern of hill administration and valley administration.

The divides were nurtured and the commonalities played down by militant organisations, and leaders. And the divides are many. Between the Hindu Meiteis, the majority who live in the valley, and the Christian tribals -- Nagas, Kukis, Peiteis, etc -- who have the hills. Between the tribals -- Nagas versus Kukis, etc. And even within tribes; for example, within the Nagas.

What all ethnic/tribal groups have in common is that some time or the other, they have risen up against the Indian State.

So you have nearly 40 militant organisations -- could be more than the number of working ATMs -- in Manipur. They are spread across the hills as well as the valley.

In Senapati district, the Nagas and Kukis live side by side. The two tribes have a long history of bloody conflict, and one thing in common. They feel that Meitei-dominated Imphal won't listen to their demands -- and hence the common form of protest: Blockades meant to hurt the valley people.

"Among the common people, there is no divide," says Irengbam Arun, editor of the Manipuri language daily Ireibak. "Every hill man has a friend in the valley. A family (almost). When he comes from the hill he will stay in that home and they will be like a family. When a person from the valley will go to the hills, he will be welcomed like family too. The divide is a recent phenomenon that groups like the NSCIN-IM exploited to establish the pan-Naga identity."

"This kind of nationalism is dangerous, it is suicidal," says Loitongbam, who runs a non-governmental organisation called Human Rights Alert. "We have seen that in Eastern Europe." He points out to the "deeply symbiotic" relationship between the hill and the valley people.

He is not the only one who says that.

Manipur: Bleeding from politics

"People calling blockades don't seem to understand that people in the hills also suffer," says Arun. "We have survived over 60 days of blockade in the past. People say even if we have to eat grass we will not surrender. It's the politicians in the hills who are playing up the ethnic thing. They never go back once they come here (in the valley) -- the student leaders, the politicians, the contractors. They buy land here and settle. Because life in the villages is extremely hard. And the simple common people in the villages, who have very few needs, they (the leaders) will tell them that it's the people in the valley that are eating up their share. When it's these politicians and contractors that are eating up their share."

Loitongbam points out, "The worst sufferers of the blockades were in the hills. Because rice from the valley was also not going to the hills. You can survive without petrol, but it becomes very difficult to survive without rice."

But is it just about the leaders in the hills?

Turns out, in petrol-starved Imphal valley, there was no real shortage of petrol during the blockade. The valley consumes 72 kilo litres of petrol daily, says a government source.

The government rationed petrol, which led to overnight queues at petrol pumps. Then the government hiked up supply to 82 kilo litres, with paramilitary convoys escorting tankers in through Highway 53, the other highway into Manipur from mainland India which is worse than NH39. Still the lines remained. So the supply was hiked to 112 kl.

Still, petrol was being sold in black.

It does not require a lot of maths to see that some people made a lot of money from the blockades.

"The ones who make money are making money," says another Imphal resident, also a government servant. "It's all politics. If the valley people feel the pinch the leaders will tell them it's because of the hill people. That will ensure they vote for their own politicians in the February elections."

'Are the troops there only for the security of the VIPs?'

"Is the government anti-Parliament," asks a person associated with the Sadar Hills District Demand Committee, the umbrella Kuki organisation that started the blockade. "In 1971, a Parliament Act approved the creation of six hill districts. In 1972 it was re-approved, but Sadar Hills was left out. Since then five districts have been created, only Sadar Hills was left out. Why? The United Naga Council, All Naga Students' Association Manipur, are they for the integrity of Manipur or breaking up?"

The UNC's spokesperson S Milan sent rediff.com 18 documents to show that the Government of India has signed four agreements with the Naga groups over the years that say there will be no redrawing of districts without Naga consent.

'The United Naga Council will not accept bifurcation of Naga areas without the wishes and consent of the Nagas,' says one of the press releases. 'The Nagas have been resisting arbitrary encroachment and creation of artificial boundary ancestral homeland since colonial period and hence any attempt on the part of the government of Manipur to create Sadar Hills District without consulting the Nagas will be strongly opposed.'

One of the reasons the blockades could not be broken was because in Manipur, only women lead the agitations. A move that checkmates the security forces.

If you are surprised, don't be. This is the state of Nupi Lal (literally women's war), the 1939 uprising against the British in which Manipuri women armed with sticks fought pitched battles with bayonet-bearing-British Raj troops.

But even the 'women can't be used force upon' theory is a half-truth.

On October 27, K Ranjit, Manipur's minister of works, was detained by Sadar Hills district demanders. The Kuki women blocked him in.

A special team of Imphal East, Imphal West, Thoubal and Bishnupur police commandos rushed to rescue the minister. They opened fire, burst teargas shells. Two women were injured -- seriously, insists the Kuki source.

"Who are all these troops for, are they only for the security of the VIPs," asks Loitongbam. "If the prime minister or Sonia Gandhi had visited Senapati, would they have allowed the blockade to go on?"

Has the state government learnt any lessons?

"Besides force, there are several ways (of opening up a highway)," says Arun. "But the politics..."

Both the Nagas and the Kukis say they have only suspended their agitations.

The Kukis already have signboards declaring 'Sadar Hills District'. A new district will mean more police cover in a hostile area. It will also mean government jobs and services.

The Naga teams refused to meet the state government interlocutors, so the state government team went and met them three times. The Nagas say the talks could not make headway because the team included only bureaucrats and not ministers.

On August 18, the United Naga Council wrote to the prime minister, saying, 'The Memorandum of Understanding/agreements had clearly enunciated that the GoM (government of Manipur) would take ethnic affinities into consideration in the readjustment and demarcation of boundaries. However the GoM has wilfully ignored this critical point of understanding and instead have encouraged the demand for creation of Sardar Hills District through bifurcation of Senapati District and inclusion of Naga villages and land in the same.'

"Our mandate is to divide along administrative lines, not ethnic lines," says a top government official who was involved in the talks. "The UNC is a front of the NSCN."

December 4, the UNC again wrote to the prime minister urging him to intervene or face 'catastrophic consequences'.

So, with no one refusing to budge, how did the blockade lift on November 29?

"They need the money," says the government official. "They collect between Rs 15,000 and Rs 50,000 per truck that comes along National Highway 39. This is festival season in the hills. They cannot afford to block the highway during this time."

The festival season will be over in January.

What lessons has the state government learned from the blockades? There is nothing much that can be done without at least a four-lane highway and a train line, insists the government source. That will be completed in 2016.

To quote one of Chief Minister Ibobi Singh's pet phrases, how unfortunate.

Watch out for Part 2 of this series: Fear and laughter in Manipur