| « Back to article | Print this article |

A House for Mr and Mrs Raina

After spending 20 years in squalid camps in Jammu, the Kashmiri Pandits, who fled their native Kashmir valley to escape ethnic cleansing, will finally move into a new township. But they are not home yet.

Archana Masih reports from Jammu on the torment of the Pandits in exile, which remains one of contemporary India's worst tragedies.

The tin doors run row by row, with names painted by hand, as if done by one of the family members themselves, a letter too small, another too big, a trickle of paint running down, a smudged fingerprint. Trying perhaps desperately to give the dignity of a home to the tiny, cramped, nine by 14 foot room allotted to each of them in a squalid camp settlement in Jammu.

The residents behind those doors, driven out of their homes 20 years ago, have lived in these slum-like quarters since their escape. They have witnessed marriages, births and deaths here; have seen their children graduate from schools and colleges; have lamented the loss of their motherland and life as they once knew it; and have brought up a new generation with no memory of that place in the Kashmir valley they once called Home.

|

For many Kashmiri Pandits this room is home now. There is hardly a door without a name.

In the sea of migrant tenements, the tiny doors bear their family names; while inside abound traumatic stories of a people who fled their ancestral homes in the dead of night, some with nothing but the clothes they wore, trying to save their lives and families when Islamic militants unleashed horrific terror on them in the mad months of 1990.

Long before Bosnia, there was Kashmir. The Kashmiri Brahmins, known as Pandits, who had lived in the Kashmir valley for centuries faced ethnic cleansing from Pakistan-supported militants to subvert the Indian State. Almost the entire Pandit population was forcefully expelled. Approximately 700,000 remain in exile since.

In Jammu city, the displaced Pandits live largely spread between four migrant camps, from where, finally, after 20 years, they will move from these unhygienic, pigeonhole rooms to apartments in a Pandit township called Jagti on the outskirts of Jammu that was inaugurated by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh last month.

Mr and Mrs Ravinder Raina; Mrs Babli Bhatt, a widow; Vinod Dhar, whose entire family was massacred in his village home, the ageing Mr and Mrs Triloknath Below; an ailing Mr Beharilal Kheda are among those who received allotment letters from Dr Singh.

They will move into their new two-room homes by the end of April.

But the hopes of another new beginning remain clouded with apprehension, as the Kashmiri Pandits continue to confront the trauma of a painful collective past.

Click 'Next' to read further...

Part II: 'Is there no place for Pandits in this nation?'

Part III: 'Wasn't what Pandits experienced a genocide?'

'My generation lost its youth'

Ravinder Raina was 22 when he fled his home in Anantnag district, western Kashmir, with his parents, five brothers and a sister.

It was March 20, 1990. It was raining hard.

The plan to escape was made secretively that afternoon, his father withdrew Rs 15,000 (now about $330) from the bank and they arranged for a truck for Rs 2,000 (about $44) to take the family out of the village at nightfall.

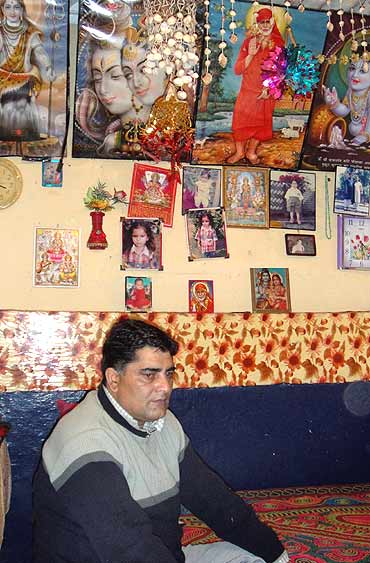

|

"Fear is far more potent than hunger. You can survive hunger, but not fear," says Raina, now 43, looking back at those days when hate spat out of loudspeakers and posters, with hostility aimed at the community, were pasted on the village wall. News about Pandits being massacred was threatening their existence.

The family undertook a dangerous 13-day journey, 11 days of which were spent stuck at the Banihal Pass, in the Pir Panjal range on the border between Jammu and Kashmir, before finally reaching Jammu city on April 2.

They were given sanctuary first in Geeta Bhawan, a shelter where scores of other fleeing Pandits had congregated. Three months later they moved to a tent and were given a room in the Muthi camp in 1992, where the Raina brothers have lived all these years.

"We had never thought we would get a new house after living a worse than worst life in the camp. Both my parents died here, I got married and had my kids here, this was home for almost two decades but camp life is not good," says Ravinder who has done odd jobs selling vegetables, manning a phone booth, assisted a thekedar (small-time contractor) in the absence of stable employment.

"I have aged in these 20 years; our life has been ruined. politicians know that our numbers are too small to matter in their electoral make or break equations. We, who have upheld the flag of India in Kashmir, have been forsaken. The battle that Hindustan should be fighting is being fought by the Kashmiri Pandit alone."

Click 'Next' to read further...

'We have lost our homeland. Our language. Our culture'

Raina is running a fever but his emotions run high and he speaks with passion.

He is also a leader of the Pandit association in his camp. On the tin cupboard are stickers of the third World Kashmiri Pandit Conference and Chalo Amarnath, referring to the pilgrimage to the holy shrine.

The bed that he sits on occupies three-quarters of the tiny room shared by his wife and two children. His sister-in-law from the neighbouring one-room house arrives with tea and biscuits.

By the door is a television where India is playing England in a cricket World Cup game.

|

Since his escape, Raina has returned to his native village two or three times. The first time he went back he found everything had changed, the site where his home stood looked like a cremation ground.

He sat down and wept.

Last year, his daughter went there for the first time, accompanied by her uncle. She returned and told her father that she did not like the place.

"We have lost our homeland. Our language. Our culture. My generation lost its youth. The government is giving us a new flat (apartment), which many of us had never expected to happen but that house will not build my future," says Raina. "The government can give us a home, but can it return us our youth, our childhood?"

Click 'Next' to read further...

Mrs Bhatt, the widow, who lost her husband in a bomb blast

'It's like folding the bedsheet we had spread on a spot that was given to me 13 years ago and being told to take my bundle and move to another place," says Babli Bhatt, a widow who lost her husband in a bomb blast in Jammu a year after her wedding.

She found out about the tragedy only a day later, when he did not return home.

"That new flat (apartment) belongs to the government. What if in time to come they ask us to vacate and move again? The government has made us into a showroom. Hamare se siyasat chalti hai (the Pandit cause is an emotive issue that keeps their politics alive)."

|

Babli lives in the Muthi camp with her daughter who is in Grade seven. She supplements the Rs 1,250 (approximately $27) she and her daughter each receive every month as relief from the government by working as a beautician to the women in the camp.

The ledge in her room is lined with bottles of nail polish, lipsticks, creams and more, that she uses for her patrons, whom she seats on the floor when she attends to them because her home has no chair.

The camp is a maze of one-room homes with haphazard extensions. Some have added a bathroom, a kitchen, while the rest use the common bathroom and toilet in each block. Each family is provided Rs 5,000 (approximately $110) per month by the government along with nine kg of rice, two kg of flour, one kg of sugar per person up to a maximum of four per family.

Often two families' parents, son, daughter-in-law and children share the same cramped room; living, eating, sleeping, studying, praying within those confines. A father mentioned how he had to step out of the room to give his young daughter some privacy to change her clothes.

It is an undignified, humiliating way to live, but there are some who are reluctant to leave. For them, this has come to mean home in many ways.

Click 'Next' to read further...

'This is our third migration'

Jagannath Raina feels he is better off in the camp than living in an apartment in a small building. At least there is a patch of open space outside, between his front door and his extended home, where a tree gives shade from the hot summer sun.

"That will be like a prison where one person can just about stand in the balcony," says Raina, who once had orchards of apple and walnuts in his village in Kupwara district. This Shivratri, one of the most important festivals for the Pandits, when walnuts are presented as an offering to the gods, Raina bought walnuts for Rs 400 (about $8) a kilo.

"We don't know who our neighbours will be in the new building. We make a small living here running odd shops. Don't know what we will do there. It would have been better to rehabilitate us in Kashmir itself."

|

When he left his home in the valley, he had hoped to be back in three or four months after the situation improved. He hasn't gone back since and feels things will never be normal enough for the Pandits to return.

"They call us migrants as if we are cattle. Even if Ram Rajya were to come we Pandits will live like beggars because we have no property left," says Shaligram Raina, among the group of men assembled on the gabba, a thick Kashmiri rug on the floor in Jagannath Raina's home.

The bright embroidered rug is common to almost every Pandit home in the camps, spread on the floor with cushions propped against the wall. Wandering salesmen from the valley stop by at the camps to sell these rugs, knowing the Pandits still cling on to these remnants that were once part of their everyday life.

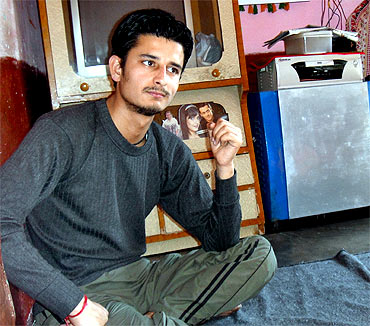

In the group of men is a quiet young man, who had served the elders tea and biscuits. Recruited as a constable in the Jammu & Kashmir police force a few days ago, he speaks fluent English and Kashmiri, and says he had wanted to become a journalist and had even freelanced for a year but unemployment forced him to apply to the police force.

"We Pandits never want to pick up the gun, but one can't remain unemployed," says Pawan Bhatt, 24, who hopes to be posted to his home district.

His family has never returned to see the home they left behind when he was just a toddler.

There is not even a photograph for Pawan to see what his family home had looked like.

To be continued tomorrow...

Part II: 'Is there no place for Pandits in this nation?'

Part III: 'Wasn't what Pandits experienced a genocide?'