| « Back to article | Print this article |

Joseph Lelyveld: 'Haven't written on Gandhi's sex life'

Journalist and Mahatma Gandhi biographer Joseph Lelyveld talks about how the father of the nation struggled with India as much as he struggled for it. Abhishek Mande listens in.

Joseph Lelyveld is probably and unfortunately better known as the man who portrayed Mahatma Gandhi to be a bisexual.

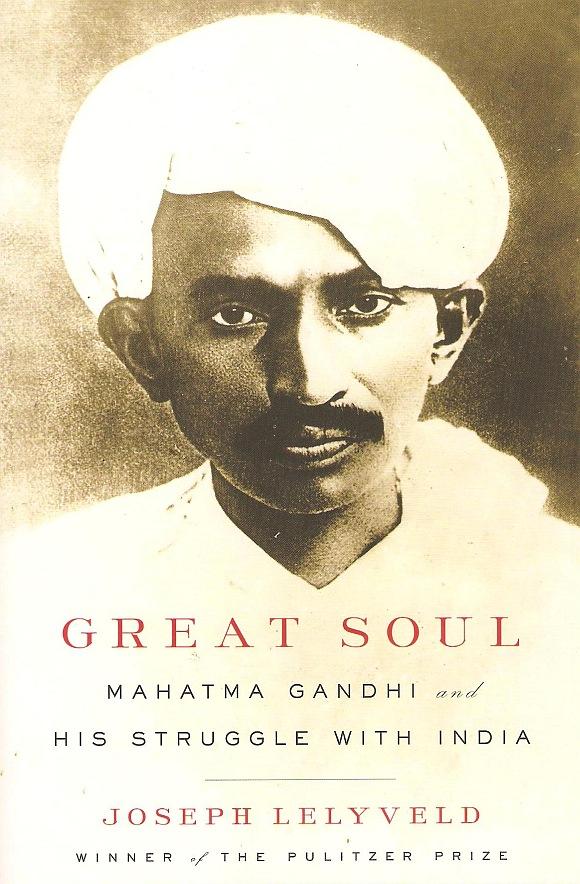

Lelyveld's book Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India ran into serious trouble after excerpts went viral online following which the Gujarat government banned the book.

The former executive editor of The New York Times was in Mumbai recently where he spoke about his admiration for Gandhi even as he defended, for what must have been the umpteenth time, the sections in his book that led to the ban.

Joseph Lelyveld was in conversation with poet and critic Ranjit Hoskote.

Before the conversation started, however, Lelyveld spoke for a little over 20 minutes explaining just why he admired the father of the nation.

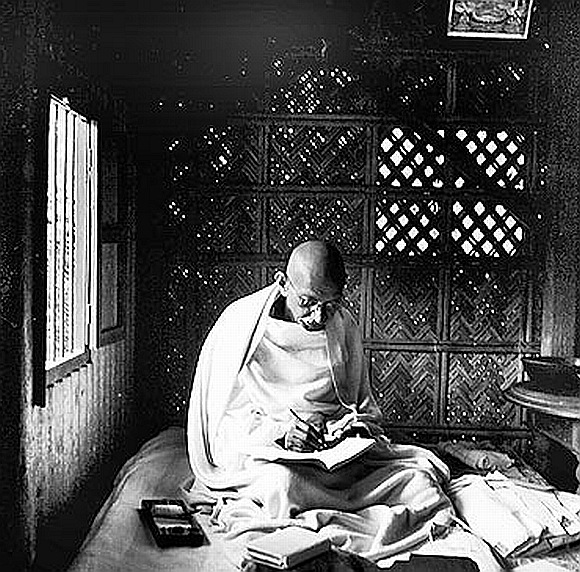

The always eloquent Lelyveld suggested, as he does in the book, that the leader struggled with India as much as he struggled for it.

In the slides that follow, we bring you excerpts along with videos of the biographer offering insight on the Mahatma's life -- from Gandhi's now controversial relationship with Hermann Kallenbach, to his equation with B R Ambedkar, Jawarharlal Nehru as well as the way he interacted with journalists who weren't necessarily reverential to him.

All videos: Hitesh Harisinghani

Click NEXT to read further...

'You can't say the Mahatma cackled and cuddled'

Joseph Lelyveld started off by quoting an old friend who he hadn't met in over 30 years who said she couldn't stay back for the speech but wanted to tell him nonetheless just what she found offensive in the book.

"She mentioned two words," Lelyveld said, "At one point I said 'Gandhi cackled' and at another point, referring to his well-known episode with his great-niece Manu I said 'Gandhi cuddled'."

His unnamed friend was rather miffed about it and by Lelyveld's account said, "You can't say of the Mahatma that he cackled and cuddled."

Lelyveld who'd said he was never taken in by 'the spiritual side of Gandhi's message' and took it 'as my purpose to pursue him at ground level' also confessed that the fact that he isn't an Indian put him in a somewhat awkward spot.

The aim of the book, he said was to go beyond the well-documented fact that South Africa shaped Gandhi's life to explore just how that happened, which was a challenge.

"I am not a devotee I am a reprobate I am not religious so I don't respond deeply to the spiritual side of Gandhi's message. I take it as my purpose to pursue it at ground level. I tried to take Gandhi as the social reformer he meant to be till the end of his life," Lelyveld said.

The idea that drove him was that Gandhi struggled with India as much as he struggled for it.

Even though he was expecting some criticism for his book given the fact that he isn't Indian, he wasn't 'prepared for some of the more negative the extreme readings' of the book.

Lelyveld singled out a 'voluntary reviewer on amazon.com who wrote about my burning hatred for Gandhi'.

"I find it hard to believe he even held the book in his hands," Lelyveld said.

Click NEXT to read further...

'Gandhi's relationship with Hermann Kallenbach is a side issue'

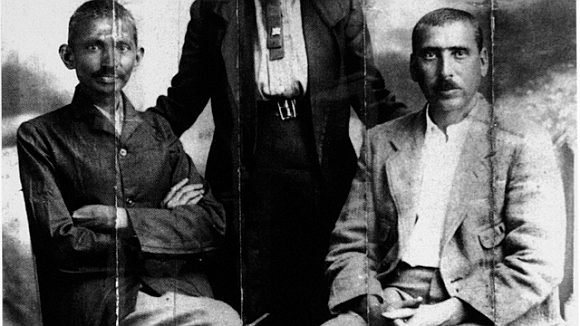

Lelyveld continued, "The banning (of my book) had nothing to do with what I thought might make it controversial, it results from my treatment of Gandhi's relationship with a Jewish architect in South Africa that went viral on the internet even before anyone had seen the book leaving me to protest as best I could as a case of mistaken identity here.

Perhaps I can clear it up. I am not Joseph Lelyveld who wrote a book on the secret sex life of Gandhi. I am the Lelyveld who thought he wrote a book on Gandhi and his struggle for social justice in India.

It would be easy to caricature Gandhi's close friendship with the architect Hermann Kallenbach, as sexual at some level that concludes that it was sellable.

My treatment of that subject that occurs in about a page-and-a-half in a 350-page book was characterised by a Bengali scholar Partha Chatterjee as jocular indulgence. It would not be a phrase that I would have thought of but it is a phrase that satisfies me because somebody got what I was doing."

He insisted, "Gandhi's relationship with Kallenbach is a side issue in my view. What I try to demonstrate on the basis of Gandhi's letters to Kallenbach which is a wonderful collection and one that has been in the public domain for the last 20 years (it is volume 96 in the collected works of Mahatma Gandhi published by the government of India) the point I was trying to make was that it was a loving relationship and one that was very important to Gandhi."

Click NEXT to read further...

Gandhi: 'I see nothing but hypocrisy and degradation'

In an interesting observation, Lelyveld pointed out that the 'importance of Gandhi's transformation were reflected in the sartorial makeover that he began in Johannesburg in 1911-12 when he eased himself out of the law practice of British suitings and began gradual custom change that culminated finally in India when he stripped down to the loin cloth and shawl that would be his apparel for the rest of his life and one that caused Churchill to call him a half-naked fakir."

He referred to Robert Payne one of Gandhi's biographers who called (the look) '(Gandhi's) more symbolic disguise' and had quoted the Mahatma as having said, "I wish to be in touch with the poorest of poor among Indians. It is our duty to dress them first and then dress ourselves, to feed them first and then feed ourselves."'

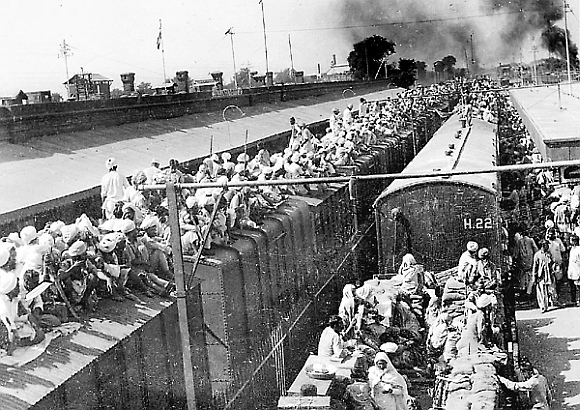

Talking about Gandhi's struggle with India, Lelyveld pointed out, "In August 1947 when independence was declared, Gandhi had to recognise that each of the values he said would be essential to India's freedom had been brushed aside by the movement he invigorated, led and personified.

That of course did not stop him. Never was he more heroic nor less affected than in the last year or so of his life -- the year independence was achieved which coincided with the ethnic cleansing and mass killings in the frontiers of the Muslim majority areas of Bengal and Punjab.

He himself went to Bihar after a period in East Bengal. There he learns that Hindus had been slaughtering Muslims to the cry of Mahatma Gandhi ki Jai. That discovery showing how few of his supposed followers had understood his message appals him and makes him wonder in his darkest moments whether he has accomplished anything at all.

'These jai shouts stick in my nostrils," he says. On Independence Day he is absent from the celebrations. Instead he fasts. "This is a sorry affair," he says."

Lelyveld added, "Of course (Gandhi) struggled for India but it strikes me that he struggled with India too. Perhaps he sensed that all along. In 1915 after he returned from South Africa, he wrote to Kallenbach, "I see around me nothing but hypocrisy, humbug and degradation. But underneath it I trace a divinity that I miss in (South Africa). This is my India. It may be blind love or ignorance or my own imagination. Anyway, it gives me peace and happiness.

"Even as he struggled for India and with India we realise that he would've have had it any other way. Few human endeavours and dreams are ever completely fulfilled. Gandhi's dream and example strike me as exceptional and noble. And maybe I am more moved by this noble failure than his undoubted success," he said.

Click NEXT to read further...