| « Back to article | Print this article |

An entire family of 23 massacred. Only he survived

Vinod Dhar's entire family was massacred when he was just a teenager. He now has a government job and a flat allotted by the government in a township for Kashmiri Pandits in Jammu but almost a decade later, the horrors of that night remain with him.

Archana Masih reports on the trauma of exiled Kashmiri Pandits, which remains contemporary India's worst tragedies. Part II of a special series.

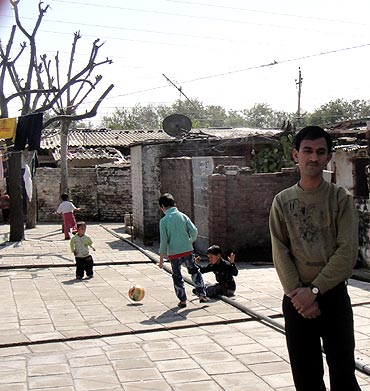

It is a Saturday morning and Vinod Dhar's door is locked. Children play cricket in the alley outside while a woman washes a pile of clothes outside her door with water from a rubber hose. "Do you want a chair to sit while you wait?" she asks politely with a shy smile.

Dhar, a wiry young man, who has by now got word that he is being looked for, comes from behind the bathroom block with a bucket in his hand and clothes on his shoulder. Excusing himself till he finishes his morning ablutions, he disappears briefly.

|

On his return he borrows two chairs and a stool from the neighbours and sits down outside as the children continue to play cricket a few metres away.

Dhar is 27 and has been through a tragedy so gruesome that he hasn't been able to recover from that trauma, that grief. He works as a clerk in the state secretariat and feels life is a struggle from birth to death.

He has a government job that many Pandit families in the camps look upon as the ideal employment, one that provides stability, a steady income and pension. Something that many young men who arrived from the valley two decades ago did not have access to, because they had either crossed the age limit or did not qualify.

But Dhar seems some place else, far away, unaffected by the routine, the ritual of everyday living. As if cloaking his immense pain by going through the motions of a daily schedule -- get up, go to work, come back, eat, sleep, move to Srinagar when the government secretariat shifts there during the summer months, stay at the hotel, get into the vehicle that takes the staff to the Srinagar secretariat in the morning, eat at the hotel...

"It has jolted me for life. It has left me scarred. People say I am lonely, that I should get married but I am not mentally prepared for marriage. No one can help mitigate your pain," says Dhar, haunted by January 25, 1998.

Click 'Next' to read further...

Read Part I of the special series here: A Home for Mr and Mrs Raina

Read Part III of the special series here: 'Wasn't what Pandits experienced a genocide?'

'This wound will remain with me till I die'

It was the day before Republic Day. Vinod was 14 and had spent the afternoon playing cricket with his friends.

That evening men dressed in army uniforms came into his home. They were offered tea by the family. Vinod was on the terrace when he heard the sound of sustained gunfire. When he came down, after the sound of bullets had ceased, he found the terrorists had gunned down his entire family -- parents, brother, sister, uncle -- and relatives from three other neighbouring Pandit homes.

Twenty-three Pandits were killed in the Wandhama (Srinagar district, northwest Kashmir) massacre that shook the country and the Diaspora. Vinod cowered in fear, hearing the wails of his mother, sister and relatives before they died.

|

"I remember that night vividly, especially when I am alone and weak. This wound will remain with me till I die," says Vinod, remembering how then prime minister Inder Kumar Gujral had visited him after the massacre and assured him that the government would look after him.

"Since 1998 I was in government custody, I was put in a boarding school and then completed my graduation from Jammu University."

When he became an adult, he says he realised that some relatives had cheated him of the ex-gratia payment that had been provided to him by the government. "I lost it all. Lucky are those who have parents. If the government had not looked after me, I would be nowhere."

After grade 12, he had wanted to join the Shri Ram College of Commerce in New Delhi. He says the government had told him to get admission in Delhi if he so wished but things did not work out and Vinod continued his education in Jammu.

Click 'next' to read further...

'The situation changes so quickly in Kashmir'

He has still not seen Delhi and hopes to make the trip there some day and asks if it is possible to get a copy of the photograph of him receiving the apartment allotment letter from Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

Dhar goes on to speak about his desire to join the J&K state administrative service, for which he had appeared earlier but had not qualified. "I want to keep trying. We all should keep trying," he says, once again looking at the sky.

The state government has recently announced 6,000 jobs for Pandits in the valley, as a measure to attract them back to Kashmir. According to government reports 2,000 Pandit youth have joined posts in the valley, but many Pandits feel that though the government is giving employment, the situation in the valley still remains risky.

|

"The situation changes so quickly in Kashmir," says Dhar, referring to the unrest in the valley last summer when, in sustained encounters between security forces and young stone pelters, 117 people had died over five months.

When the government secretariat moves back to Srinagar, so does he. Dhar expects to shift into the government-allotted apartment at Jagti in two or three months and does not express much emotion about it.

Home ceased to have any meaning since that Republic Day eve when his family was brutally killed, his home burnt.

"Kabhi kisi ko mukammal jahan nahi milta (No one ever gets a perfect world)," he says quoting Urdu poet Nida Fazli, getting up to return the borrowed chairs to his neighbours.'Can't they find a tiny place for us Pandits in this vast nation?'

In two days Priyanka Dhar's grade 10 exam was to begin. Her books lie on the bed in the lone room she shares with her parents and elder brother. A sliver of the corridor is cordoned off for a kitchen where there is hardly enough room to stand in front of the gas stove.

Her father asks her to make tea as he dashes out to his small shop to get some biscuits.

No Pandit home lets you leave without offering tea and biscuits; if it is lunch time they will insist you stay for the meal.

|

Bharatbhushan Dhar says he once had a three storeyed house with 10 or 12 rooms in Kupwara district, northwest Kashmir. His home of the last 15 years in the Purkhoo camp, Jammu city, is stacked with trunks one on top of each other, a bed, clothes heaped into piles, a broken cooler. On the wall hang framed pictures of Hindu gods.

"It would have been better if they had given us a government job rather than a flat (apartment). A government job could have sustained an entire family. Relief is good for the aged, what the educated youth need are jobs," he says, pointing out that the government should have initiated a scheme whereby every migrant Kashmiri Pandit family would have been given at least one government job.

"Or they should have given us some land where we could build a home with a loan against our properties left behind in Kashmir."

Ten years ago, his kidney was removed. He shows the scar and says his health has been on the decline since.

"There are some families with four members with government jobs, while others have none. Ek ghar mein chirag, doosrey mein andhera (There are some houses glowing as a result of government jobs; while others are plunged in darkness)."

Click 'Next' to read further...

'We want a Hindustan-like Kashmir in Kashmir'

There are 40,000 educated Pandit youth. Recruitment for 3,000 posts were initiated under the prime minister's special employment package for Kashmiri migrants, out of which 1,906 were selected and 1,179 joined their new posts in the valley, says a brochure released during the prime minister's visit.

"When our young Pandits take up these jobs they have to give a signed affidavit that they will not leave if the situation deteriorated; it implies that if they leave they will not get the job back," says Shaligram Raina from the Purkhoo camp.

|

Ruing the marginal count of Pandits in politics and working as senior bureaucrats in the state, the group of men at the Purkhoo camp mention how the community did not have a single member in the state legislative council and barely one or two Indian Administrative Service officers.

Vinod Kaul, an Indian Administrative Service officer who has been relief commissioner for the Kashmiri migrants for the past six years, says there are 17,000 Pandits employed by the central and state governments; of which approximately 4,000 are employed by the state government.

Recently, state minister for revenue, relief and rehabilitation Raman Bhalla told a group of students from Chicago University that the situation was improving in the valley and about 4,624 migrant families had applied to return.

Yet many feel things will never be the same again for them to return and there should be a separate state carved in the Kashmir valley where the exiled Pandits can be settled.

"We want a Hindustan-like Kashmir in Kashmir, a land where people from all states can live in peace," Ravinder Raina, a resident at Muthi camp had said, referring to the demand for a separate homeland in Kashmir which envisages Union territory status, governed directly by the central government.

His demand resonates at the Purkhoo camp, with a phiran-clad (kurta-like Kashmiri robe) Shaligram Raina, a man who speaks with a fiery passion that reflects his helpless pain.

"Bharat is such a vast nation. Can't they find a tiny place for us Pandits in this vast nation?"

To be continued tomorrow...

Read Part I of the special series here: A Home for Mr and Mrs Raina

Read Part III of the special series here: 'Wasn't what Pandits experienced a genocide?'