| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Water is an emotional issue for India and Pakistan'

Through accusations, denials, rhetoric and man-made borders flows a river. The Indus, which originates from Mansarovar in Tibet and is some 2,880 km long, is vital for the millions living on its banks.

Since the partition of 1947, the use of the waters of the Indus and its five eastern tributaries has been a major dispute between India and Pakistan.

Pakistan has often slammed India, accusing it of 'stealing' water. It has claimed that the projects on the Indian side are depriving it of its share of water. New Delhi, meanwhile, dismisses these allegations and reasons the dropping levels of rivers to climate change.

Gitanjali Bakshi, who recently authored a report titled The Indus Equation for the Strategic Foresight Group, states that water shortage problems in Pakistan is not a case of obstruction by external forces but rather a case of wastage and unequal distribution by internal forces.

In an e-mail interview to rediff.com's Vipin Vijayan, Bakshi talks more about the emotional issue between India and Pakistan.

Click on NEXT to read further...

The Indus equation

Your report titled 'the Indus Equation' deals with the water issues between India and Pakistan. For a layman, there's not much clarity on the issue. Could you throw some light?

Like most rivers in the world the Indus River does not recognise political boundaries. It crosses over Tibet, India, Pakistan and Afghanistan before finally emptying into the Arabian Sea at the foot of the Sindh province in Pakistan.

The two main benefactors of the Indus River waters are Pakistan and India. It took nine years of negotiations before the two nations signed the Indus Water Treaty in 1960 with assistance from the World Bank.

Under the IWT, Pakistan was allotted roughly 80 per cent of the river water of the Indus through the western tributaries (Jhelum, Chenab and Indus) while India was allotted the rest of the water via the eastern rivers (Ravi, Beas and Sutlej).

India was also given customary usage of water on the western rivers for agricultural purposes and for run-of-the-river electricity-generation projects.

Most of the disagreements between India and Pakistan concerning water arise over the western rivers of the Indus.

Water is such an emotional subject these days that extremist organisations like Jamaat-ud-Dawa (social wing of the terrorist group Laskhar-e-Tayiba) have taken up the cause of water vociferously in speeches and rallies stating that India is damming water meant for Pakistan and that a jihad must be waged to save Kashmir, the 'jugular vein' of Pakistan.

'Pakistan's claims must be backed by facts not emotions'

Pakistan says that the Kishenganga dam project in Kashmir threatens its agriculture. How much truth lies in Islamabad's claim? Is Pakistan's agriculture totally dependent on Indus rivers?

Pakistan claims that the 100 km diversion of the Kishanganga river caused by the project, will affect roughly 133,000 hectares and 600,000 people who depend on agriculture and fisheries.

This claim still needs to be backed up with substantial evidence and transparent calculations. The Kishanganga project is currently in the Court of Arbitration -- the highest mechanism for dispute resolution provided under the IWT.

It is here that the legal differences over the interpretation of the treaty (whether this tributary of the Jhelum can or cannot be diverted) and the technical arguments over the design of the project will be decided by a team of international and Indo-Pak water experts.

The points of difference over the Kishanganga project are elaborated in much greater detail in the report but yes around 70-odd per cent of Pakistan's population and territory depends on the Indus River (the only other two rivers -- Makran and Karan provide an infinitesimal amount of water in Balochistan) and close to 95 per cent of the total water usage is dedicated to agriculture.

It is probably this huge dependence on the Indus river that drives Pakistan's 'lower riparian anxieties' (riparian area is the interface between land and a river or stream) a term used often by water expert John Briscoe. Pakistan's anxieties regarding shared waters should be addressed by all means but on the basis of fact and reason not emotions and misconceptions.

'Pakistan adopts a different interpretation of IWT'

The Kishenganga dam project was okayed in the Indus Water Treaty. So why is Islamabad crying foul about it?

Pakistan adopts a different interpretation of the legal stipulations provided in the IWT.

Pakistan refers to Article IV (6) that calls for the maintenance of channels while India submits to Annexure D Paragraph 15 (iii) which permits inter-tributary diversion precisely for the purpose of hydel plants which is what the Kishanganga project is.

As mentioned before, the Court of Arbitration will decide how to resolve these two interpretations but what is important to note is that there is an institutional mechanism in place to take care of these disputes should they arise.

Several other countries do not enjoy water agreements with one another let alone such a specific and 'water tight' treaty.

'IWT needs to take climate change into consideration'

Analysts now feel the need to update certain technical specifications in the IWT. What, according to you, are the changes that need to be incorporated in the treaty?

In my opinion, there are areas where the treaty could be expanded upon and updated.

The 'Future Cooperation' section can elaborate further on an Integrated Water Resource Management approach. Water agreements around the world are now moving toward a more 'water demand' and 'water management' perspective that looks at how we can use existing water efficiently and reduce unnecessary losses rather than simply focusing on how we can increase supply. Working towards a 'sustainable' Indus River should be the key.

There should be joint cooperation to mitigate the effects of climate change -- an issue that was not really recognised in the 1960s.

Lastly, there should be constructive talks held on acknowledging the technological advancements that have been made with regard to run-of-the-river dams.

The issue of spillway gates and 'flushing' to remove excess silt is a common point of difference that has come up in the case of the Salal project, the Baglihar Dam and now perhaps the Kishanganga hydel plant and this should be addressed once and for all.

Technological design in the 1960s might not have foreseen the modern designs of run-of-the-river projects today but there are clauses in the treaty that account for this lack of technological foresight and point towards 'sound and economical' design.

Once expanded and updated, the IWT can provide an even greater degree of depth and relevance to transboundary water agreements as a whole and can even be used to inform future water agreements amongst other nations.

'Jammu and Kashmir has suffered'

For Kashmiris, the water dispute has long been a reason for lack of or no development of the region. Your comment.

Development in Jammu and Kashmir has definitely been curtailed because of the restrictions placed on water development of the western rivers under the IWT and both Pakistan and India can do their part to alleviate these effects.

State business groups repeatedly tell the government of India that they could collect approximately $13 billion (about Rs 68,500 crore) from electricity exports if they were allowed to harness the full hydroelectric potential of the state (20,000 MW).

It is estimated that Jammu and Kashmir could have increased its area of irrigation by 2.47 lakh hectares more than its current irrigable land (2.3 lakh hectares) if it was allowed to utilise its water resources optimally.

Run-of-the-river dams must stay. However, efforts can be made to improve irrigation networks in J&K and develop hydel capacity in a mutually beneficial way.

Where does the water go?

Media reports have quoted experts as saying that Pakistani complaints are aimed at diverting attention within Pakistan from the internal water row (including water wastage). Your thoughts.

Low water supply in Pakistan is mainly a result of water conveyance losses.

According to Former Pakistani Foreign Minister S M Qureshi, in a very candid interview he gave to a Pakistani news channel in 2010, the "total average canal supplies in Pakistan are 104 million acre feet. However the water available at the farm gate is about 70 MAF. Where does the water go? It's not stolen in India, it's being wasted in Pakistan".

6.5 MAF of water is also lost due to siltation (collection of silt in dams that blocks storage capacity), water efficiency does not exceed 36 per cent, only 0.25 per cent of Pakistan's GDP accounts for water sector development and 6.8 million hectares of irrigated land was affected by salinity as of 2007-2008.

All these factors effect water supply in Pakistan and they are matters of internal water management in Pakistan. Apart from this there is disparity in the distribution of water among the provinces.

Punjab receives certain preferences to water allocation due to 'historical use', Sindh, being the farthest away from the headwaters, suffers the consequences of a lower riparian state and the effects of seawater intrusion from the Arabian Sea.

Pakistan occupied Kashmir does not enjoy any water allocations under the 1991 agreement, which distributes the water amongst the provinces of Pakistan, because it was not recognised as a province during the drafting of the agreement.

These water distribution disparities amongst Pakistan's provinces can also be the cause of low water supply in certain parts of the country.

'Terror outfits are manipulating the facts'

What do you make out of terror outfits operating in Kashmir using the water issue to suit their interests?

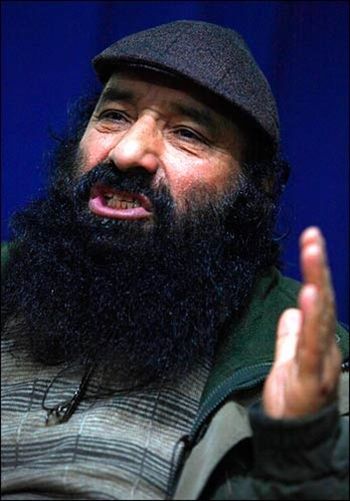

I find it exceptionally disconcerting. It could lead to 'water terrorism' -- Hizb-ul-Mujahideen's chief Syed Salahuddin has mentioned in his speeches that blowing up Indian dams would not be difficult and that if they blow up the Wullar barrage, India would lose Rs.2 billion. (Nawa-i-Waqt, Jinnah, March 22, 2010)

Water is an emotional topic and anti-India terrorist organisations have chosen to manipulate the facts and use the subject as a means to recruit the millions of destitute people in Pakistan's rural population.

'Water refugees' is a new term emerging within the world of security and after the 2010 floods Pakistan has many of them. It is important to monitor water refugees and make sure they do not fall pray to terrorist groups like JuD, HuM and others.

'If glaciers vanish water supplies in Pak will be in peril'

How much impact does climate change have on the dynamics of the India-Pakistan water dispute?

Forty-sixty per cent of the water in the Indus river is comprised of glacial meltwater and will therefore be effected significantly by climate change.

Qin Dahe, former head of China's Meteorological Administration, said that the Tibetan glaciers are retreating at a faster rate than other glaciers in the world and once these glaciers vanish "water supplies in Pakistan will be in peril."

'Heavy monsoons not India caused 2010 floods on Pak'

Some Pakistani analysts like Zaid Hamid have in the past accused India of engineering the floods that devastated the country in 2010. Do you agree?

No, I don't agree. Pakistan has blamed Indian damming for the devastating flash floods in July 2010 that impacted nearly a fifth of Pakistan's land area.

However, according to NASA's satellite images this catastrophe was the result of unusually heavy monsoons, potentially caused by the La Nina effect that enhances the Asian monsoon.

NASA also stated that the high temperatures in the northern Indian Ocean and waters of the coast of Pakistan in the Arabian Sea could have enhanced the monsoon rains as they were warmer than usual.

'India's involvement in Afghanistan is no secret'

Pakistan recently accused India of expanding its 'water hegemony' to Afghanistan by supporting Afghan development projects along the Kabul River. Why is Islamabad raising eyebrows on India's efforts?

The Kabul river is a shared river between Afghanistan and Pakistan and a tributary of the Indus.

Afghanistan has plans to build 12 dams on this river with the help of the international community and India and the World Bank have offered their assistance.

The unique status of Pakistan as upper and lower riparian and the location of the 12 dams being built is elaborated in the report but what is important to note is that the matter is not so much about Indian hegemony as it is about a shared-water agreement between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

India's involvement in development projects in Afghanistan is no secret and advancement of the water sector is an integral part of development, especially in a war-torn country like Afghanistan.

Afghanistan and Pakistan have tried to reach an agreement over water-sharing in 2003 and 2006 but these failed and such discussions could be renewed if Pakistan is worried about the water being supplied from the Kabul River.

Using the IWT to form a Kabul River agreement could also be something to consider as all three parties involved in the IWT are present, while Afghanistan is also a riparian in the Indus river basin.

A war over water?

Do you foresee an I ndia-Pakistan war over water?

Water is an important topic today and in the years to come it will become an integral part of security studies especially in countries like India and Pakistan that have large agricultural economies and growing populations.

However, whether this important resource will be used as an area for cooperation or a reason for conflict depends on political will and strategic foresight.