| « Back to article | Print this article |

'There is no room for complacency in India'

New York-born S Mitra Kalita moved to Delhi to experience Indian life. On her return to the US she wrote a book about her unpredictable two-year adventure. Aseem Chhabra reports...

In the fall of 2006, US-born Indian-American journalist S Mitra Kalita took a big step to move to India to help launch a new business newspaper -- Mint. Her artist husband and their two-year-old daughter joined her in Delhi.

Kalita had been to India many times as child visiting her large extended family in Assam. But she had never lived in India. Her two-year stint in Delhi exposed her to the changing India -- the new liberalised and energised economy in bigger cities and the pockets of India that were being left behind.

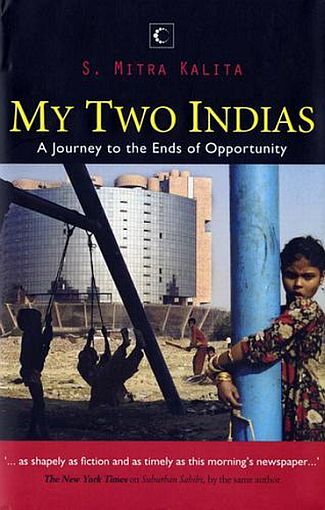

Kalita, now a senior special writer at The Wall Street Journal in New York, has recently published My Two Indias: A Journey to the Ends of Opportunity (Collins Business, India).

The book is a memoir of her perceptions of the India she was hoping to live in and the adjustments and understandings she made with the India that she discovered. This is her second book. Her first book -- Suburban Sahibs -- focused on three Indian immigrant families living in New Jersey.

Kalita was recently in Delhi for the launch of My Two Indias. Over a lunch interview, Kalita talked about her relationship with the new and evolving India; her time there as a journalist and as a daughter of Assam; what surprised her and disappointed her about India; and most important what she took back with her to the US.

Click on NEXT to read further...

'The real India I saw was not the one I expected'

Why two Indias? There are actually many more Indias, right? There was the India in Assam you visited during your childhood; the India that you were anxious and excited about for your job at Mint; there was the India that you discovered different from the India you were looking forward to. So what was the real India you saw?

I guess the real India I saw was not the one I expected. It was basically a collusion of all of the above. I had already reported quite a bit from India. I wrote about the IT industry for Newsday. But it is much different when you come here with your family. You parachute in and do the stories.

There was this sense of a work place that had been completely liberalised. I did a story about a company in Bengaluru that would make its employees put in Rs 10 in a pot, every time someone said sir or madam. Within a week they said that habit would be broken. It was an attempt to flatten hierarchy. There was another company where they had the workers vote on what colours to paint the walls.

'India is so competitive, cutting corners becomes a way of doing things'

What about your own company?

Oh people would call me madam all the time.

The reporters also?

Yes, the reporters. I know it's a very silly example.

It is very hard for people to lose that habit...

Right at the same time you are trying to encourage innovation in the work place. You may think that these things are cosmetic, but actually they matter quite greatly, because it relates to people's perception of themselves in the company. At Mint I felt really lucky that I had a team that eventually went on to commit to very hard-hitting journalism.

What was your experience with journalists in India?

The challenge in India is that it is so competitive, cutting corners becomes a way of doing things. At Mint we had a code of conduct that spelled out the need to get all sides of a story, something that we take for granted in western journalism. We also ran training sessions for the journalists. So it became an example of a very modern media, in some ways like what the IT sector was doing in India.

But as compared to the journalists you met at The Washington Post and the Journal, how would you rate Indian reporters?

Indian journalists have a whole lot of heart and hustle. Every morning I would get those nine newspapers at my doorstep and they were a reminder of what those reporters were up against. The complacency that has set in American journalism was pretty absent in Indian journalism.

'There is no room for complacency in India'

In the US I could be working on a feature story for three or four days. In India if you have a great idea you have to do it right away, because everybody else may also have that same idea.

When I went back to the Journal, it was redefining itself as a more general newsy relevant paper. So I could apply the lessons I learnt in India. It is interesting because once upon a time your Indian journalism experience counted for nothing. But this was such a great opportunity to say that the West can learn something from Indian journalism.

I still think that a lot of the downfall of the newspapers in the US -- yes, some of it was caused by the Internet, but some of it, in other industries too, was driven by complacency.

In India you just can't be complacent. From the time you wake up and turn on the faucet -- and there is no guarantee that you will get water -- there is no room for complacency in India.

'Liberalisation has bypassed the northeast'

You talk about your other India -- your parents' home in Assam and that the liberalisation has not reached the northeastern states of India. Do Shillong and Guwahati have malls?

They have malls. The consumer revolution is going on. But you don't have mass employment in the form of new industries. For example, what's happening in Gujarat with new investments is not happening in Assam. The problem in Assam has to do with its current state of insurgency. No company is going to go there as long as security is a big threat.

That being said I always see Assam is a great metaphor for the rest of India because many states are going through some form of insurgency.

So these aren't issues just limited to Assam. But yes, liberalisation has bypassed Assam and the northeast.

The other thing is that there has been an incredible amount of brain drain from backward states like Assam for jobs in BPOs (call centers) and the hospitality sector. Now who am I -- the daughter of an Assamese immigrant in the US -- to decry that? For many of them it has been a great exposure and a necessary economic tool to uplift their homes and families. But it has created such a social change.

You go to a wedding and there will be a handful of people under the age of 30, because everybody's children are outside.

'Education is such a lynchpin for the aspirational India'

Were you disappointed by anything in India?

Education!

Does this relate to your daughter's education? But with your media connections you could have gotten your daughter admission in a good school in Delhi.

But I refused to do that. We had a rule that when applying for admissions, we would not use connections and not give donations.

But I also mention in the book that 60 per cent of children in parts of India are studying in private schools, and education for poor families remains the single biggest expense. This is such a lynchpin for the aspirational India.

I met a taxi driver in Sarnath who sends his children to a private school run by a group of Italians.

I mention Sarnath in the book where there are billboards after billboards advertising English medium schools. People don't send their kids to government schools, because the teachers fail to show up.

'It is actually easier to get into Columbia than an IIT'

I was talking to a friend in Mumbai. His son's entire private school class is applying to colleges abroad.

Absolutely! We did a series on Indians students in the US -- kids who had only attended private schools in India. After going through that education they were worried about going to Indian colleges and finding the environment stifling.

But also there are so many students, you have to weed them out. And so it is actually easier to get into Columbia than an IIT.

So I was disappointed in the education system as a manager and as a mother. As a manager I was disappointed because colleges in their rush to place students in this booming economy would give us [recruiters] 15 minutes to make the decision.

It is a frenzy and you fail to ask the young people one of the most important career counseling question: What do you actually want to do with your life?

As a mother I was disappointed because I had a two year old who would bring homework and they would ask her to colour only within the lines and to make sure she always coloured the banana yellow. At the age of two they are being restricted in their thinking.

So you came back because you had a job opportunity but because you had already started to think about your daughter's education?

Yes!

'People in power do not want to get rid of corruption'

At your book event I asked Mani Shankar Aiyar whether liberalisation was really essential or good for India. What is your perspective?

There is no turning back, of course. I actually believe that it did create certain hope and belief in a country. The problem is that you have certain sectors that Mani talked about such as agriculture that are not benefiting from liberalisation.

The reality is that manufacturing could be a great way to employ mass amounts of people and pull them out of poverty.

I follow a woman who runs a children's clothing factory outside Gurgaon and she deals with government inspectors who want a piece of the pie. She has unions who are asking for their bribe. If you employ more than 100 workers, there is no benefit in doing that. The people in power do not want to get rid of this corruption.

Despite the liberalisation there are still some sectors that work under the license raj. Education is one of those examples. Why is it so hard to get an engineering college accredited in India?

I write in the book about a case where school inspectors demanded a white Pomeranian dog and meals waiting for them. So as long as those people can profit from the reality of there not being enough engineering colleges, what liberalisation is going to occur?

'I couldn't be boxed into the 'NRI returns to India''

When did you start to write the book? It emerged out of your Mint columns right?

Actually when I first started to write the book, it wasn't a memoir. Similar to my first book I was trying to cast characters like in a movie.

But I became incredibly self-conscious about writing about India, because I was an outsider. I think my expertise has become stronger having worked here and having researched various elements of labour, education, politics.

But I did feel that just as I couldn't be boxed into the 'NRI returns to India,' I could use myself as a vehicle for what India was going through. At Mint initially I resisted writing in the first person. But then I started to write in first person in reportage form, to help a reader navigate.

And you brought in you, the NRI, in first person?

Yes. And the columns were very well read although some people did hate me. I would write about how my house was invaded by our guests from the village. You know that movie Atithi Tum Kab Jaoge? I wrote that column, before that was a movie.

'I miss fresh lime soda, the vibrancy of Delhi...'

Often times I had relatives who had not travelled beyond Kolkata and they had expectations that I would serve them dinner. I am from the city where you put your food on the plate and start eating. But in Assam the woman hovers over the table.

I talked to colleagues and some of them had set limits on their guests. When you live in a country with a booming economy and people don't just work nine to five, who has space and time for house guests who think they are supposed to be divine?

I wrote a piece about almirahs [Indian style metal cupboards]. I thought everybody writes about the new India, but let's just for a moment pay respect to where we came from. I interviewed a guy who couldn't throw away his almirahs and had placed them on the stair landings. He said his wife was ready to kill him.

What did you miss the most about America when you were there and what do you miss the most about India now?

I missed the efficiency of the US. There is a system to doing things that I was used to. Obviously there is an Indian system, but I didn't know it right? I missed my nuclear family -- my parents and my brothers.

You didn't miss food, like bagels?

Bagels maybe, but by the end of our stay there was a woman who had started to make bagels in Delhi. And you know bagels in New York can be hit or miss too.

What I miss about India is that I was able to form legitimate relationships with my larger family in Assam. I was always revered, because I used to come as a child, the NRI cousin. But now I was an adult. They never could picture our lives in the US nor could they afford to visit.

Now in the US, I miss things like fresh lime soda. I miss the vibrancy of Delhi. Last night I was sitting with a bunch of journalists and we were talking about scandals, who moved where and who is writing what.

There is a certain familiarity of the Indian work place. It can be maddening, but it is something I will never get back again. At my farewell party at Mint I looked around the room and realised that I never worked in an environment where I felt so incredibly supported. Maybe there is an ethnic and cultural element to it. In India when you open up your tiffin box, people put in their hands to taste your food. That's the way lunch is in Indian workplaces. At first I was taken aback, because Americans do not share lunches.