Photographs: Peter Caton Beatriz Lopez and Peter Caton

British photographer Peter Caton and Beatriz Lopez visit Kasargod district in north Kerala, whose residents have been plagued by the spraying of endosulfan pesticide, the use of which was recently banned by the Supreme Court of India. From families completely breaking down to pushing innocents into the dark well of irrecoverable diseases, the endosulfan menace has often been described as equally devastating as the Bhopal gas tragedy.

A panorama of rolling hills distinguishes the landscape of Kasargod, a northern district of Kerala. With fertile land and an abundance of water, the cashew industry once flourished amid dense vegetation, red earth and coconut palms.

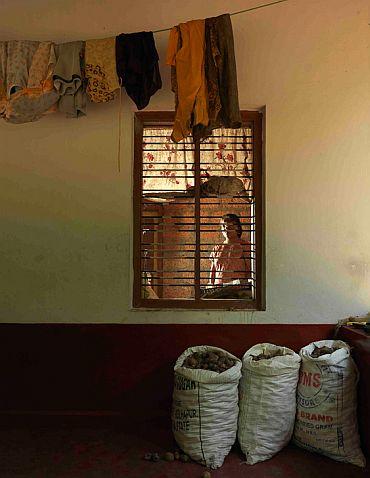

These forested valleys are home to rural communities still living off the land, such as Mamatha's family, who collect betel-nuts as their main source of income.

The household of six adult siblings and their elderly father live in a small, overcrowded cottage, which they may have to sell to fund a series of operations that will remove the tumour distorting Mamatha's face. Mamatha is a confirmed endosulfan poisoning victim.

..

Endosulfan already banned in over 80 countries

Image: Freshly picked cashew fruit with the nut still attached in KasargodPhotographs: Peter Caton

Endosulfan, an organochlorine insecticide, acts as a contact poison for a wide variety of insects and mites and has been used extensively worldwide on food crops like tea, fruits, vegetables and grains.

Famed for its capacity to increase agricultural productivity, endosulfan has been officially banned in Kerala for 10 years. For a period of 25 years that led to the state ban, indiscriminate aerial spraying of cashew plantations contaminated the soil, water sources, wildlife and the communities of the Kasaragod district.

Already banned in over 80 countries, 127 represented governments agreed on a worldwide ban at the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants last April.

The India government delegation contested the otherwise unanimous consensus. Facing huge financial losses due to the nation's agricultural industry's heavy reliance on endosulfan, an 11-year phaseout period with financial support was negotiated; giving government-appointed scientists time to develop a cost-effective, alternative pest control.

The people of Kerala are leading the social and political front in demanding a permanent national ban in the wake of a correlation with adverse health reactions, including cancer, congenital malformations, mental retardation, reproductive disorders, infertility and neurological disorders affecting several generations within the Kasaragod district.

The pesticide has crippled the lives of four brothers in this family

Image: Brothers Abdul Rahaman, 27, Abdhul Hameeneb, 34, Abdul Kadhar, 20 and Ahmad Kabir, 25, all endosulfan victimsPhotographs: Peter Caton

Manufacturing and usage of endosulfan in India has recently come to a complete halt. Chief Justice Sarosh Homi Kapadia of the Supreme Court imposed an eight-week national blanket ban, demanding an expert committee -- formed by the Indian Council of Medical Research and agriculture commissioner -- submit a conclusive study to determine the toxicity of endosulfan before it can be lifted.

For the Aboobekar family, the geno-neurotoxic pesticide has crippled the lives of four brothers; all born mentally retarded with slow motor skills and a disfiguring mouth malformation.

Brothers Abdul and Ahmad, aged 20 and 25, both attend a community-run school for mentally challenged endosulfan victims called 'Bud'.

First of its kind in Kasaragod, the panchayat-run initiative highlights the problem's severity. In a class of approximately 25 attendees, the brothers can expect the company of up to 10 neighbours ranging from ages 3 to 25.

Mrs Aboobekar remembers when the community still lived in thatched houses. Locals would fetch firewood from the fields and water from exposed wells, their skin often coming into contact with endosulfan.

"In the mornings you would see a mist and there was a strong smell from the pesticide that would give us headaches."

She faced the consequences for raising her voice against use of endosulfan

Image: Leelakumari Amma played a key role in having endosulfan banned in KeralaPhotographs: Peter Caton

Union Agricultural Minister Sharad Pawar recently announced that there is lack of evidence to prove the negative impact on humans and denied anti-endosulfan protest from any state governments other than Kerala and neighbouring Karnataka.

Kerala was the only state where endosulfan was aerially sprayed, an approach not scientifically investigated at the time.

Leelakumari Amma battled the plantation corporation to the high court in 2000 and played a key role in having endosulfan banned in Kerala.

Employed as an agronomist by the agricultural department of her local panchayat, she observed an abnormal amount of illnesses in the community, which triggered her suspicion of chemical poisoning.

"People had to walk through these fields that had been sprayed as there was no transportation. Children walked through the fields. There were no butterflies; there were no birds; so it was concrete evidence for my suspicions."

She filed a petition after her numerous letters of concern to the plantation corporation were ignored. Leelakumari claims she was harassed by the management of the plantation corporation at her home.

She also received anonymous derogatory letters and death threats. The decision for a ban was reached on October 18, 2000, and put into practice by 2002.

A year to the day of the victory, she was struck by a truck in a head-on collision that has left her with long term injuries. She suspects foul play.

He believes the plantation corporation violated human rights

Image: Dr KumarPhotographs: Peter Caton

The extent of negligence from the plantation corporation (Central government owned) is unclear, with innumerable stories ranging from disregarding health and safety protocol to allegations of intimidation by officials towards activists that supported the state ban in Kerala.

Dr Kumar, an activist associated with Pesticide Action Network, also accuses the plantation corporation of harassment and false allegations that he had 'vested interests'.

According to studies published in 2002 by the National Institute of Occupational Health, a lethal concentration of endosulfan residue was found in human blood samples.

The samples were taken from Padre village where Dr Kumar's medical practice resides; fuelling a debate among scientists over the authenticity of the data.

Dr Kumar attributes the alarming number of chronic conditions within the local population to be directly linked with the geography of Padre village, which is nestled in a bowl-shaped valley and surrounded by hills covered in cashew plantations.

"Many small streams run through the village. They originate in the plantations." He believes the plantation corporation violated human rights by not protecting water sources when aerially spraying the pesticide.

'The plantation corporation knew it was a dangerous chemical'

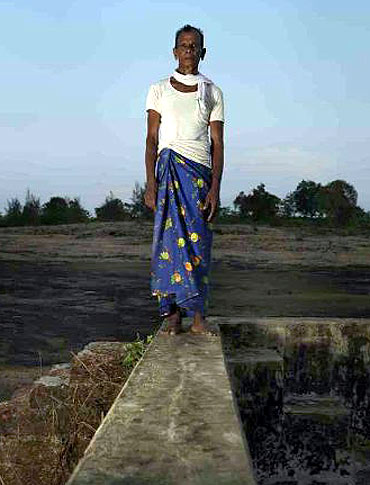

Image: During the first year of spraying endosulfan, many fish and chicken died, says Achuthan ManniyeniPhotographs: Peter Caton

Achuthan Manniyeni, a former employee of the plantation corporation, agrees with Dr Kumar's accusation. He claims corners were cut by not following proper health and safety protocol for the employees, communities and environment.

"During the first year of spraying, many fish and chicken died, so the plantation corporation knew it was a dangerous chemical."

Achuthan was one of the six employees who prepared the pesticide for spraying in his area. The concrete mixing tub was located in a cashew field several meters from one of the district's water basins, which was not covered properly during the aerial spraying.

It was also common practice to dump empty endosulfan cans in a nearby well. Gloves, soap and towel provisions were not supplied to the employees according to Achuthan, who suspects that the management instead pocketed the allowance.

Furthermore, he claims endosulfan stock was freely handed to local farmers after the ban was imposed on Kerala, and that one of his colleagues was contracted to bury containers on a nearby mountain in order to get rid of excessive stock.

The exact location is unknown as all of his five colleagues have since died from symptoms associated with endosulfan poisoning.

'Endosulfan has been produced to protect the trees from bugs'

Image: Local cashew farmers Ashraf, Mohammad disagree that endosulfan is hazardous to human lifePhotographs: Peter Caton

Local cashew farmer Ashraf disagrees that endosulfan is hazardous to human life, citing his own health as an example.

He blames natural causes for the ailments people have been suffering. "Endosulfan has been produced to protect the trees from bugs. An increase of insects can also be harmful to the people."

His business partner Mohammad says, "They say endosulfan has harmed a lot of people, but when you look at the economic side it is a pathetic situation."

He recalls that when the cashew crops were treated with endosulfan, farmers collected an average of 700 kilos per day. Untreated, they collect 15 to 30 kilos per day. "People have lost a lot of income."

Until recently, endosulfan manufactured in India constitutes 70 per cent of the global market, with its total exports valued at about Rs180 crore.

Since the Green Revolution in India, agriculture has become a big export. India ranks second worldwide in farm output with almost 30 per cent of its booming economy coming from agriculture.

Without a total ban in India, smuggling across borders into Kerala has proved difficult to contain. With the eight-week temporary national ban, reports from different states are beginning to emerge, particularly from Orissa where the chemical is said to be openly available in the state capital and in Madhya Pradesh where stock is being sold at a premium rate of Rs 500 instead of Rs 250 per litre.

'We want another child, but we are scared'

Image: Abhilash Bhat rolls around with difficulty on a floor mat at homePhotographs: Peter Caton

Rumours of farmers hoarding stock are circulating as the monsoon crop season is about to commence. Endosulfan, an off-patent product, is cheaper than any other patented pesticides on the market.

Meanwhile, people neighbouring or living within the predominantly national government owned cashew plantations continue to suffer the consequences of what had became a highly profitable industry; satisfying the demand of western palates at supermarket prices.

In the latest 'Progress of Rehabilitation of Endosulfan in Kerala' report, Dr Asheel's compiled data for the 'Department of Health and Family Welfare of Kerala' records 4,270 confirmed endosulfan poisoned victims and over 500 deaths to date.

The poisoning effects are diverse and devastating for the victims, their families and the wider community.

In Karadka village, Abhilash Bhat -- a 10-year-old boy -- rolls around with difficulty on a floor mat at home. One of thousands of endosulfan pesticide victims, his head weighs 20kg, roughly four times the weight of an average adult head.

Born with hydrocephalus, a rare medical condition in which there is an abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain, his head has swelled to enormous proportions. The cranial pressure has shrunk his brain, causing total mental retardation.

Like so many children of Kasaragod, Abhilash Bhat is evidence of the congenital damage caused by endosulfan contamination.

Sreedevi, his mother, had already miscarried two previous pregnancies and her first child died within 10 days from the same congenital genetic condition. Doctors believed Abhilash would not survive and his parents were warned that conceiving another child would only lead to the same heartache: "We want another child, but we are scared."

The high-risk operation needed to save his life may well bankrupt the family, who already struggle to make ends meet.

Over half of their wage, earned from the collection and selling of betel nut, is spent on medical and travel expenses incurred from Abhilash needing hospital treatment every three days.

Many believe endosulfan poisoning is the curse of God

Image: Endosulfan victim Rahina is partly cared by her parental grandmotherPhotographs: Peter Caton

Both born blind, sisters Rahina and Rasna are six and nine years old. Their parents Rajan and Rohina say the difficulty of supporting two blind children with their minimal income earned through labouring work has forced them to separate the children.

Rasna is now living with her maternal grandmother, while Rahina is partly cared for by her paternal grandmother who lives in the family home.

After Rahina was born, they gave up on the prospect of a larger family for fear of conceiving another child with the same genetic disorder.

People were ignorant about the high toxicity of endosulfan, believing in curses and 'the will of God'.

She has been confined to her home

Image: Unable to support herself on her weak, child-size legs, Sujatha lives her life bound to her home.Photographs: Peter Caton

Sumitra and her husband Ganeshrao, a plantation corporation worker, thought they had been cursed by the Serpent God Jataadhari and spent over Rs 2 lakhs on religious rituals performed at a temple.

Their 16-year-old daughter Soumya and 14-year-old son Arunkumar, would frequently experience fevers that eventually left them mute and crippled. As the children are partially blind and deaf, they rely on smell to identify people and make simple gestures to have their needs met.

Soumya drags herself across the home's concrete floor as she is unable to walk. Rarely leaving their home and with no social services or physiotherapy, they receive little stimulation to improve their condition.

Sujatha was struck down with a recurring fever at the age of four which left her hospitalised on several occasions.

At 28 years of age, her body has not developed properly and she has limited mobility in her limbs. Unable to support herself on her weak, child-size legs, she lives her life bound to her home.

Frustrated by her speech impairment, she speaks of her on-going struggle with depression. Sujatha has no opportunity to marry and live a normal life, as she is completely dependent on her mother. Her mother explains that her energy levels prevent her from staying awake extended periods of time and that an exhausting menstrual cycle (three times per month) causes her low blood pressure.

A year ago, a local youth group arranged monthly visits of a physiotherapist who is also an ayurvedic doctor, but her improvement has been minimal and she is still experiencing ongoing pain in her legs.

Medicine was also received from a local government hospital for four months, but the home delivery service was suddenly stopped without an explanation. When questioned, the hospital explained they had run out of medicine. Sujatha was never clear what the prescription was for.

Lack of funds prevented her from receiving follow-up physiotherapy

Image: Gulabi cries in her kitchen, overwhelmed by her circumstancesPhotographs: Peter Caton

Gulabi lives in a small shack with her husband, mother-in-law and four children. An endosulfan victim, she experienced her first symptoms after the birth of her second child.

Her medical records say she has a 'loco-motor disability'. Gulabi's low blood pressure and weakness in her legs led to a fall which shattered her right femur.

An operation to replace the bone has failed to improve her walking ability, and a lack of finance has prevented her from receiving follow-up physiotherapy.

The family survives off the Rs150 per day her husband earns as a seasonal forager.

'Bathing him requires the assistance of two people'

Image: A fever left Shafi paralysed overnight, with a damaged nervous system and mental retardation.Photographs: Peter Caton

Shafi is a 27-year-old man living within the confines of a bare concrete room. As a healthy 6-year-old child, he played in the cashew fields that surrounded the family home where endosulfan was aerially sprayed for three months of the year. A fever left Shafi paralysed overnight, with a damaged nervous system and mental retardation.

Elderly and coping with physical pain, Shafi's widowed mother, Aisha, has little opportunity to rest; staying awake most nights to comfort her insomniac son.

Her other son, a rickshaw driver, is the principle provider, while her four adult daughters make bidis to supplement the family's stretched household income.

Aisha clasps her head with her hands as she describes the financial strain resulting from Shafi's disability; "soiled mats need to be replaced regularly, and detergents for washing his clothes are expensive. Bathing him requires the assistance of two people."

Aisha is relieved at the prospect of receiving an additional Rs 2,000 monthly allowance for Shafi. She says, "Our family has experienced many days when there was a shortage of food."

'My prayer is that this should never happen again'

Image: Parents of victims like Carmina Costa, who has been promised a consolatory yet miniscule compensation, fear for future generations' lives.Photographs: Peter Caton

In an attempt to calm growing pressure, a Rs 5 crore compensation package has been offered by the plantation corporation to be distributed in schemes.

A comprehensive package is being launched by the Kerala state health department to be available in the 11 worst affected panchayatts.

Benefit cards are being registered under three categories; Class A, the worst affected victims, expecting to receive Rs 2,000 monthly pensions; an amount barely enough to cover medical expenses, let alone supplement the potential income loss of carers.

"My greatest difficulty is not being able to leave my daughter unattended," says Sreeja, a mother of two young daughters.

Her six-year-old daughter Chaithany suffers from a severe neurological disorder and is unable to control her limbs or communicate. Sreeja is a fulltime carer, bound to her single roomed home, while her husband keeps the family afloat with menial labour; earning only Rs 250 per day.

On December 18, 2010, chairman K G Balakrishnan of the National Human Rights Commission compared the endosulfan devastation on par with the Bhopal gas tragedy.

Kasaragod district is the worst known case of endosulfan poisoning on a mass scale. Activists like B Ashraf who is associated with the NGO Thanal, is the secretary of the Punchiri Club (a local activist group) and health inspector for the Muliyar panchayat are referring to the atrocity as a "government chemical warfare on its own people".

While the question of evidence remains -- blocking an immediate, permanent national ban -- Dr Kumar puts conflicting scientific evidence into perspective: "You can argue anything because you cannot test on humans. You have to consider the circumstantial evidence."

In the meantime, parents of victims like Carmina Costa, who has been promised a consolatory yet miniscule compensation, fear for future generations' lives.

"My prayer is that this should never happen again. So many children, so many mothers are suffering. This is my prayer to the government."

article