| « Back to article | Print this article |

India's future lies in its hands not in America's

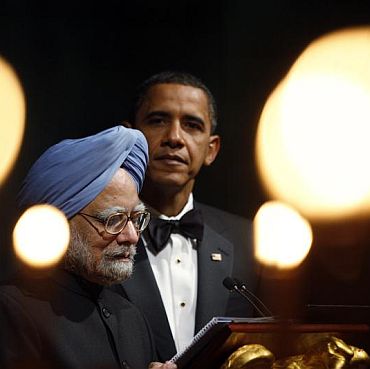

The 54-page report titled Toward Realistic US-India Relations, coincides with US President Barack Obama's visit to India next month.

The 54-page report titled Toward Realistic US-India Relations, coincides with US President Barack Obama's visit to India next month. An advance copy of the report, authored by CEIP Nuclear Policy Programme Director George Perkovich, was made available to Rediff.com

It said 'the United States will have much more influence on vital global issues --international finance and trade, the future of the nuclear order, peace and security in Asia, climate change -- that also shape the environment in which India will succeed or fail.'

'Therefore, the United States can best serve its interests in those of India by ensuring that its policies toward India do not undermine the pursuit of wider international cooperation on these global issues," the report added.

Please click on NEXT to read further...

'India should be valued in its own right'

'Yet, India's interests, policies and diplomatic style will often diverge from those of the United States, including in relations to China,' it said, and noted that Washington and New Delhi 'both want their share of economic, military and soft power to grow relative to China's -- or at least not to fail -- but both will also pursue cooperation with Beijing.'

Thus, the report predicted that 'for the foreseeable future, the three States will operate a triangular relationship, with none of them being close partners of the others,' and reiterated that 'this is another reason why promoting multilateral institution-building is a sound US strategy, and why India should be valued in its own right, not as a partner in containing China.'

Taking aim at the likes of veteran Indian diplomat and erstwhile foreign secretary Kanwal Sibal, former Bush administration official Daniel Twining and Indian-American scholar Sumit Ganguly, who have all expressed a nostalgia for the Bush administration and assailed the Obama administration for trying too hard to cooperate with China in addressing regional and global challenges and has not done enough to bolster India, the report declared, 'Like a Rorschach test, commentary as President Obama prepares to go to India tells as much about the authors as it does about the president, his policies, or India.'

'Many in India believe the US has tilted towards Beijing'

The report added, 'For their part, many American commentators see Chinese and Pakistani monsters sneaking up behind Obama's thin, unsuspecting frame and wonder why he is not standing closer to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.'

'Nostalgia often colors perceptions and mixes fact with wishful projections,' it said, and cited the example of former Bush administration officials Evan Feigenbaum arguing that 'Many in India believe that the Obama administration has tilted its policy toward Beijing in a way that undermines Indian interests,' even as he acknowledges that 'Obama's China policy is broadly consistent with that of every US president since Richard Nixon."

'Bush did more for India than he did for any NATO ally'

To lend credence to his argument, Perkovich pointed out that 'Blair urged the Bush administration to try to ratify the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, revive negotiations on a climate change treaty, and expend political capital to revive the Middle East peace process. He was rebuffed on all counts.'

'India, on the other hand, spurned Bush's pleas to join the military coalition in Iraq and blocked his efforts to restart world trade liberalisation and isolate Iran. Bush responded by giving India a global nuclear deal so lopsided that one of its architect (whom Perkovich names as Philip Zelikow) called it a "gift horse."'

The report said, 'The Bush administration offered more and asked for less of India than it did of any other country, save perhaps Israel.'

'Special treatment of India is unrealistic'

'Careful analysis of US and Indian interests does not show such a close convergence,' it said in answering the very question is raised and therefore recommended that 'a sound and sustainable US policy toward India should more accurately reflect multiple American, Indian and global interests.'

The report said, 'Rather than maintaining the pretense of partnership, a truly pro-India policy would acknowledge that India has different near-term needs and interests as a developing country than does the US, even as its recognises that each will benefit in the long run from the success of the other.'

Thus, it predicted, 'Most of what the US government can do for India lies in the broader global arena, and most of what India needs at home it must do for itself.'

Chinese rise in the region can be peaceful if...

This study, co-chaired by former senior Bush administration officials Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage and Under Secretary of State Nicholas Burns, argued that while neither the US nor India seeks 'containment of China, but the likelihood of a peaceful Chinese rise increases if it ascends in a region where the great democratic powers are also strong.'

The Carnegie report said, 'While India's democratic character is intrinsically of tremendous value, it serves little instrumental power for US interests.'

It acknowledged that the 'United States traditionally proselytises democracy around the world and would very much welcome the credibility that Indian leaders could give it in developing countries if they teamed up.'

Don't enlist India to reform the world

'India's admirable long-term struggle to perfect its own democracy is the most important contribution it can make to the larger cause of democracy promotion around the world,' it said, and added: 'Washington should not disappoint itself by trying to enlist India is larger American projects to reform the world.'

The report said, 'India and the United States share the virtue of being democracies, but this may be more its own reward than a source of abiding friendship or useful cooperation,' and argued, 'India and the United States are both too imperfect to get away with telling themselves or other states how to govern.'

US must publicly back India's UNSC bid

The Carnegie report while acknowledging that 'this body can hardly claim to represent international society in any dimension if it does not include India,' said, 'India is not yet prepared to partner with the US in strengthening many of the rule-based elements of the international system -- the project that has been the objective of American leadership since the end of World War II and, with renewed vigour, in the era of globalisation.'

The Carnegie report while acknowledging that 'this body can hardly claim to represent international society in any dimension if it does not include India,' said, 'India is not yet prepared to partner with the US in strengthening many of the rule-based elements of the international system -- the project that has been the objective of American leadership since the end of World War II and, with renewed vigour, in the era of globalisation.''The broadest indication of India's divergence from US positions in the United Nations is its record in the UN General Assembly,' the report said, 'where it has voted with the United States approximately 20 percent of the time."

Nuke deal won't energise Indo-US ties

'Ironically, there is evidence that the nuclear deal will not accomplish its primary objective of transforming Indo-US relations,' it said because nuclear energy was 'simply not important enough to the Indian economy or policy -- outside of globalised urban elites -- to transform India's political willingness to accommodate American interests where they do not already converge with its own.'

The report said that strategic affairs expert C Raja Mohan, an avowed advocate for the deal as being the transforming agent of the relationship, now argued: 'Progress on the bilateral defence/security agenda is the key to Delhi's willingness to cooperate with Washington across the board.'

'India is daring US to apply sanctions on its companies'

'India has refused to cooperate with recently passed Congressional sanctions to block exports of refined petroleum products to Iran and investment in Iran's energy sector. In effect, India is daring the US to apply extraterritorial sanctions on its companies.'

Consequently, it said, far from winning India's cooperation on this issue, India's refusal to go along with his highest international security priority of the US had 'emboldened Iran and made other States less inclined to support the US in isolating Iran.'

Can India or Pak help US out of Afghan quagmire?

'Understanding these limits does not give us an answer to the question of what the US should do in Afghanistan it the current strategy proves unsuccessful,' it said.

But it predicted, 'It does clarify that neither Pakistan nor India is going to significantly help the US out of the quagmire, and that American policymakers will have to repair relations with both India and Pakistan in the aftermath of any unhappy Afghan denouement.'