| « Back to article | Print this article |

'India is respectful of its history'

Ranging from Canada to Australia to China, India and Egypt, the British Empire was seven times larger than the Roman Empire at its highest glory in the last quarter of the 19th century, when London ruled a quarter of the earth. It ended with Britain handing over Hong Kong to China.

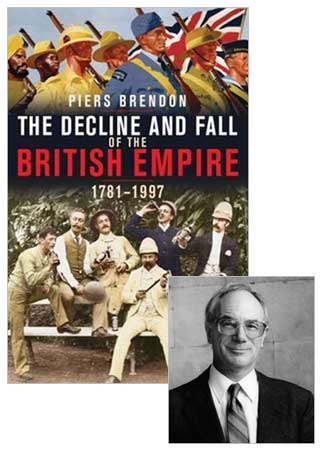

Though Brendon, 69, looks at the empire's fortunes throughout the globe, much of the book focuses on India. The book is praised by critics and fellow historians not only for its penetrating and lively appraisal of a mighty historical era but also for being a cautionary story.

Brendon also offers a startlingly new look into the mind of Thomas Babington Macaulay, member of the British parliament who in 1833 was appointed the first law member of the Governor General Council. He went to India in 1834 and while serving on the Supreme Council of India between 1834 and 1838 he led to the adoption of English as the medium of instruction in higher education, rather than Sanskrit or Urdu.

Piers Brendon spoke to Rediff India Abroad's Arthur J Pais.

Among the many intriguing stories in your book is the one about the moustache culture during the Raj.

Fellow historians tell me that they have not come across those stories in other history books. This was a serious business; it is called the Moustache Movement in the book. It was not that the British had discovered the moustache in India.

During the Napoleonic Wars, a few British officers had started imitating French officers who spotted the moustache who had learned from the Spanish that a man of resolution wore whiskers.

In India, the British discovered that their sepoys were not amused that their British had no moustaches. The sepoys believed moustaches to be a sign of virility. And they laughed at the bare-lipped British, thinking that they were effete and feeble.

The lower officers began sporting moustaches in the 1830s but it took quite some time for the officers to start wearing them. In 1854 moustaches were made compulsory for European troops in the Bombay unit of the army and were enthusiastically adopted everywhere else.

I believe the size of the British officers' moustache grew proportionately to the expansion of the British Empire. In England, an industry grew supplying items to maintain the moustache. In some cases, moustaches were even clipped and trimmed until they were curved like sabers and bristled like bayonets. Even British civilians began to stiffen their upper lips.

As the moustache became a symbol of British rule and superiority, the Indian servants of the Raj were forbidden to have fancy moustaches. The most symbolic of the Moustache Movement was a poster of Lord [Horatio Herbert] Kitchner's recruiting effort during the Great War in 1914.

His picture -- in which he declares 'your country needs you' -- was seen across the world, and so was his moustache. I write that moustaches, which became the symbol of the empire, largely derived from the empire building in India -- just the way the Romans learned the habit of wearing trousers from the barbarian tribes.

'I am amazed at the way some of the old British clubs are maintained in India'

It took me more than six years. I did a lot of research for it in London. I did not travel much except for visiting India several times. There were good reasons for it. For one, India was certainly the most important of the British colonies and it is the jewel in the crown of this book.

Secondly, it is a pleasure to travel through India. It is a country that is respectful of its history. They don't smash up old parts of the regime. If they don't want to keep part of the past in public, they put them away.

In Lucknow, there is a huge collection of old British statues. I am also amazed at the way some of the old British clubs are maintained in India. In the course of my research I visited a number of these clubs including the Tollygunge Club in Calcutta. In Kerala, I visited the High Range Club in Munnar where they have high range hats hanging and there is so much of old-fashioned headgear there although it was part of India's imperial history.

I visited a club in Ooty which has pictures of Queen Victoria and many things connected with the Raj.

Some reviewers have said your book, while rejecting the revivalist notions about the glory of the British Empire, is still a moral audit of the Empire. And you make room for the good deeds.

I believe that many people in the British foreign service were attracted to India -- and other countries -- by a moral calling. They were not missionaries. But they worked ceaselessly and without succumbing to corruption to bring about reforms that are appreciated even today in many former colonies.

They worked to abolish sati in India, for example. They were officers like General Sir Charles Napier, who questioned cultural relativism and promised to act according to the custom of his own country. He said, 'When men burn women alive we hang them.' In Africa many civil servants and missionaries endeavored to put down slavery.

'Macaulay would be less dismissive of India if his Sanskrit dictionary had not fallen off the boat'

I know Macaulay is widely reviled among many Indians for asserting the superiority of European learning. His thought that Indians should receive a Western education and learn the English language was disliked by many in India.

At Cambridge when I mention him to Indian students they do not react well. He is like a demon figure to them. I can understand that. But he is a complex figure and my book seeks to show that. Macaulay did not have any knowledge of Indian classics but I wonder what might have happened had he known Sanskrit and the rich Indian literature.

Macaulay was a brilliant writer and he could learn a language within few weeks. He would have been less dismissive of India if his Sanskrit dictionary had not fallen off the boat during an Indian visit and had he learned that language. He learned Portuguese instead.

People in Europe were just learning to appreciate the richness of Sanskrit and its literature then. Even then Macaulay would have appreciated the Sanskrit legend, lore and literature available then. He would not then have been a chauvinistic person and if he had learned Sanskrit, he would have a treasure trove of literature.

But it so happened that he did not see the richness on his doorstep. Instead, he acquired a very blinkered approach to Indian culture.

Is there anything else about Macaulay that we do not know much about?

I certainly do not share Macaulay's prejudices. But I remember he promoted the freedom of press and equality before law. He accommodated to India more than many Englishmen. He found Calcutta despite its horrible climate less suffocating than the House of Commons.

It is true that Macaulay disparaged Indian history and literature, but his ultimate purpose has been largely obscured. He aimed to fit Indians for Independence and to teach them to embrace European institutions of government.

Many conservative politicians in England opposed the spread of Western education because they were afraid it would undermine the British Empire. But Macaulay wanted the opposite thing to happen. He believed that the empire had a finite life.

He knew that the empire could offer India a lot of things including Shakespeare and a civil service that was not corrupt.

He even declared that the ending of the Raj would be 'the proudest day in English history' -- provided that his compatriots left behind an empire immune to decay, 'the imperishable empire of our arts and our morals, our literature and our laws.'

When you look at India's freedom movement, you will find this was a legacy many Indian nationalists were prepared to accept. And we also know how English became the vernacular of emancipation, how English and American thinkers influenced Indian leaders, and how substantial part of the Indian freedom literature was published in English.

'The spirit of imperialism is far from dead'

The Indian Mutiny -- to use its British name -- was a military uprising, political coup, a religious war, race riot and also a peasant riot. But the mutineers were never able to transform the uprising into a war of independence.

For one thing, many Indians -- princes as well as ordinary people -- joined the rebellion. The mutineers also had to fight the Sikhs who were supporting the British. I have wondered about the usage mutiny.

I ask how it could it be a mutiny when the British were the mutineers who had no right to be in India. How could we (the British) expect loyalty from the Indians? The word mutiny was used to justify the catharsis, the horrible torture and killings of thousands of mutineers or suspected mutineers.

Some of the British radicals who questioned the ill treatment and the killings pointed out that the British had no right to assume loyalty from a land taken and held in force, and governed for the benefit of rulers who were aliens in every respect of the word.

There was great deal of savagery in Kanpur, and the way the British were killed. The British felt they were stabbed in the back. They believed that this gave them a right to retaliate and their reaction was ferocious. Many British commanders were homicidal.

At Allahabad, an officer executed 6,000 people, more than were killed on his own side during the entire mutiny. There was a huge cry in England for vengeance, and retaliation that would be written in books of history. The accounts of children and women killed by the mutineers brought about an insensate lust for revenge.

Colonel James Neill, who executed thousands in Allahabad, flogged many of the mutineers or suspected mutineers and made them lick blood from the slaughterhouse floor before hanging them.

When I see what the Israelis do to the Palestinians and the humiliation they subject them to, I am reminded of what the British did to the Indians. The British retaliated against the mutineers in India in 1857 -- that was horrifying to say the least. The punishment they meted out to the Indians was far, far disproportionate to what the rebels had done.

We see such a thing whenever Palestinians attack the Israelis. And I am reminded that the spirit of imperialism is far from dead.

Once the mutiny broke, there was no way to revive the ties between the British and the Indians. Though they worked together for many decades, there was no more trust. There could be reconciliation, but it was clear that the Raj had no legitimate hold over India.

Many British newspapers used the word nigger to describe Indians, which added to the racial prejudice against Indians.

'Why nations yearn for territorial aggrandisement'

They surely contributed to the mutiny. There were Protestant missionaries whose rhetoric talked about monkey worshippers and the tantriks, and it created a lot of resentment among the Indians.

The Baptist missionaries fared better to the extent that though they were involved in conversions, they did not use the extreme rhetoric of other Protestants. Though the British government often expressed the sentiments that Indian religions should be respected especially in the army, there was nevertheless a feeling even before the 1857 mutiny that the English had not only taken over much of India but were also going to make everyone Christian.

The first Anglican diocese was founded in Calcutta in 1813 and its first bishop Thomas Middleton began attacking the 'fabric of idolatry' in India. His declaration did not gain him converts, but he was honoured in St Paul's Cathedral in London with a marble tableau, blessing two young Indians.

What are the larger implications of this book?

I offer many exciting episodes dealing with the British Empire, though there is less emphasis in it on the triumphs than on the disasters that undermined the fabric of the empire.

I argue that the deeds that won the empire, and even those that lost it, were sometimes valiant. But I never shrink from dealing with the seamy side of the enterprise. Throughout the book I seek to convey the full fascination of the momentous saga of the Empire.

When I began writing it, we were at war with Iraq. I was opposed to the war and I resigned from the Labour Party after being a member for 40 years because of Tony Blair's support for the American war in Iraq.

He legitimised the war, in a way. At the end of my book, I write that in Britain and elsewhere round the earth, empire is more than just a romantic memory. I am convinced it is the embodiment of real ambitions, and that is why nations yearn for territorial aggrandisement.

I conclude my book with the assertion that the craving for power and wealth is an atavistic instinct. And that is why we see a war in Afghanistan and a war in Iraq. I saw one colonial empire in Iraq when we (the British) were there in the 1920s and when we put up a puppet regime there. What Bush and Blair tried to do was a terrible replica of that enterprise.