| « Back to article | Print this article |

Making Lord Krishna and Kautilya relevant today

Lord Krishna, Alexander The Great and Kautilya play stellar parts in Amartya Sen's discussion with Arthur J Pais. A fascinating conversation with the Nobel Laureate

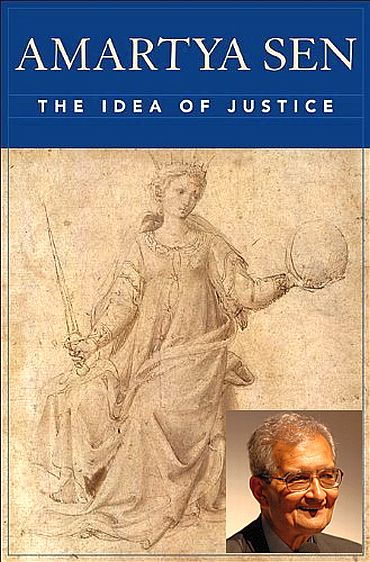

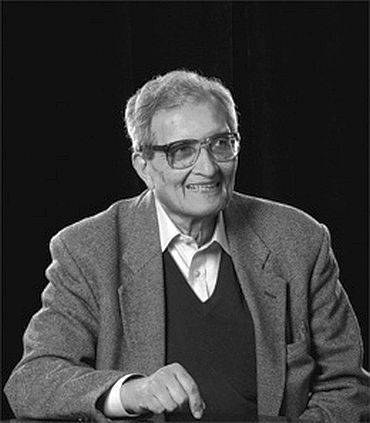

Over the last five decades, Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen has continued to be not only a provocative thinker, and inspiring teacher -- at Delhi University, MIT, Cambridge and Harvard, among other universities -- but also a writer whose books engage readers at large, even as they address deep philosophical and economic concepts.His latest book The Idea of Justice (Harvard University Press) has drawn wide praise in the popular and academic press. With a cast of dozens of thinkers, warriors, rulers, statesmen and poets ranging from Lord Krishna to Alexander the Great to Kautilya to the philosophers of the Enlightenment era in Europe to lyricist Javed Akhtar, the book by 77-year-old Sen is filled with engaging and provocative arguments and counter-arguments.

'Mr Sen writes with dry wit, a feel for history and a relaxed cosmopolitanism... The Idea of Justice is a feast,' wrote The Economist 'Nobody can reasonably complain any longer that they do not see how the parts of Mr Sen's grand enterprise fit together Mr Sen ends, suitably, with democracy. It can take many institutional forms, he says. But none succeeds without open debate about values and principles. To that vital element in public reason, as he calls it, The Idea of Justice is a contribution of the highest rank'.

'The economist reflects on our understanding of what a 'just society' really is. 'While thinkers and social reformers of many persuasions -- for example, utilitarians, economic egalitarians, labour right theorists, no-nonsense libertarians -- might each reasonably see a clear and straightforward resolution to questions of justice', he argues, 'these clear and straightforward resolutions would be completely different'.

'The economist reflects on our understanding of what a 'just society' really is. 'While thinkers and social reformers of many persuasions -- for example, utilitarians, economic egalitarians, labour right theorists, no-nonsense libertarians -- might each reasonably see a clear and straightforward resolution to questions of justice', he argues, 'these clear and straightforward resolutions would be completely different'.A product of his love affair with philosophy

Sen's book is partly fuelled by what he says is his love affair with philosophy. 'My planned field of study varied a good deal in my younger years, and between the ages of three and 17, I seriously flirted, in turn, with Sanskrit, mathematics, and physics, before settling for the eccentric charms of economics,' he has written in an autobiographical essay.

Philosophy was never out of his mind as he studied social movements, famines, illiteracy and the status and exploitation of women in India.

All through his research and prolific writings, he has remained a teacher. 'But the idea that I should be a teacher and a researcher of some sort did not vary over the years,' he wrote. 'I am used to thinking of the word "academic" as meaning "sound," rather than the more old-fashioned dictionary meaning: "Unpractical," "theoretical," or "conjectural".'

One of the reasons his books, including Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny, and in particular his latest, reach readers who are not academics is the range of his learning and investigations, and his ability to write about them lucidly and persuasively.

What makes Sen, described by Britain's The New Statesman as the English-speaking world's pre-eminent public intellectual, unique? His latest work The Idea of Justice offers a significant clue. As Oxford University's G A Cohen has said the book 'gives us a political philosophy that is dedicated to the reduction of injustice on earth rather than to the creation of ideally just castles in the air.

Amartya Sen brings political philosophy face to face with human aspiration and human deprivation in the real world, to whose improvement he has devoted his intellectual life'.

Professor Sen discussed his book with rediff.com at his Harvard office recently. Click to read on...

The Alexander tale

This comes at an interesting period of Alexander's life. He sets towards the east, he conquers Persia, he speeds through Afghanistan with great rapidity; people often forget that and tell us that Alexander never managed to conquer Afghanistan; but that's just not true. He went through Afghanistan with great speed; he encountered then serious opposition to his movement in the Punjab; and there he spent over a year, fighting skirmishes against local kings. He won them all. He was a great fighter. The Greeks, even though much extended and far from home, did very well militarily.

But, Alexander was also a student of Aristotle. He had a great intellect; he was an exceedingly sensitive human being with a level of intelligence that's enviable and he kept wondering about what he heard about Indian philosophy. He spent quite a bit of time talking with Indian philosophers.

That specific example you mention -- and there are several others like that -- is a particular case when Alexander encounters a number of Jain philosophers.

The Jains don't take much notice of him at all. They go on doing whatever they were doing. Alexander complains about the lack of interest of the Jains in this world-conquering hero and he asks them why.

One of the Jain philosophers replies: You are indeed a world-conqueror and we do know that; on the other hand you have to examine what you are doing and why you are doing it. You are far away from your home, you are bringing warfare to distant places and you have a sense that by conquering the world you have achieved something permanent for yourself. But you'll be soon dead and no matter how much land you conquer, all the land that you would ultimately need is a little place sufficient to bury you. The Indian critics go on to add: You are actually a nuisance to yourself in addition to being a nuisance to others.

Alexander is absolutely charmed by this reply. He immediately acknowledges that the philosophers are right, and does this with the same generosity, which he earlier displayed in dealing with Diogenes. Alexander accepts the hard criticism of the Indian philosophers with huge grace and understanding.

Alexander did conquer India, with his ideas

That's a human failing -- that is even when we recognise something in principle, we may not actually be able to put it in practice. What is remarkable is that he had such deep intellectual interest, and instead of trying to penalise the Jain philosophers for first neglecting and then criticising him, he appreciates the reasoning behind their position. This broad-mindedness is absolutely striking.

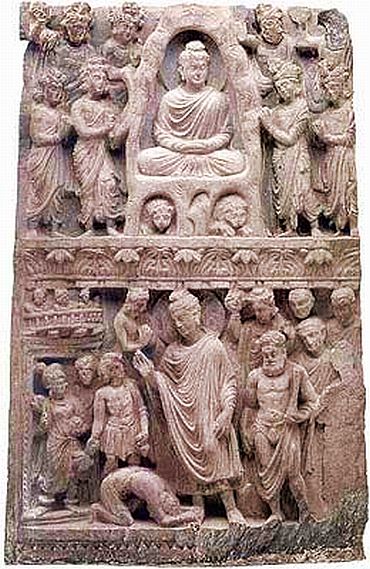

Alexander spends a lot of time in India but does not launch an attempt to conquer the country. He does not go much beyond Punjab; and decides not to take on the really powerful power in the country, based in Pataliputra [now Patna] from where the Nanda emperors ruled much of India. He cannot persuade his soldiers to undertake that big fight. So there was no military conquest of India by Alexander; but in some ways he did conquer India because the ideas that came with the Greeks -- the philosophy, the astronomy, the theatre, the sculpture -- all these would transform India in a big way.

And on the other side, the Greeks were greatly influenced by India too; and the Indian influence on the Greek thinking was quite strong. Scholars have written interesting books about the parallel between ancient Greek and ancient Indian thought -- for example Thomas McEvilly's very fine comparative book, The Shape of Ancient Thought (2002).

Some of the similarities reflected just congruence of two civilizations with distinct origin and evolution, but often the convergence reflected the influence of Greece on India and of India on Greece.

And, Alexander is a very central figure in that civilizational story. That story, I think, is very important to understand for several different reasons:

- It celebrates the Greek-Indian intellectual and artistic contact, which is an extremely important part of the heritage of the world;

- It tells us that people even though reared in very different cultures can communicate with one another and appreciate what one person is telling to another even though they were born and grew up thousands of miles apart;

- It indicates how conscious reasoning about what we are doing and why we do what we do can give us an insight that would not come without serious reasoning. Such reasoned communication is quite central to human life.

- It is also, as I try to argue in my last book, The Idea of Justice, very central to the idea of justice itself, in making us understand the demands of justice.

- And also we have to appreciate that in pursuing reason we can actually communicate across the boundaries of cultures and nations (it has become fashionable to deny that possibility).

'Incidents in my life stimulated my analytical reasoning'

You have said many times that philosophy has been of great interest to you for many, many years. Tell us how this book started and let's also talk about the practical implications of the things you discuss in the book.

I have been interested in philosophy from my childhood, and my general interest in analytical reasoning was further stimulated by various incidents in my life, like witnessing a famine, like seeing the insane killing in communal violence, like seeing the agony of huge refugee movements across the borders.

At the practical level, I was concerned with issues of justice and injustice from very early days. But then when I got seriously involved in the subject of philosophy, I saw there was a natural connection there, between thoughts generated by my experiences and my interest in political philosophy. I should admit that within philosophy my main interest initially was on purely analytical philosophy, particularly mathematical logic and epistemology.

And indeed, in my early years, I wrote on philosophy of science and on epistemology, dealing with such issues as determinism, predictability and the importance of agency, in addition to being engaged in pursuing analytical issues involved in logic and the foundations of mathematics.

But gradually over the years, my interest in philosophy moved in the direction of ethics and political philosophy, partly -- but not only -- because of my concern with welfare economics, but also because of my growing involvement with the mathematical discipline of social choice theory which is concerned, ultimately, with issues of social ethics, but uses mathematical tools.

That field of study originated in the eighteenth century with major contributions of French mathematicians, such as [Marquis de] Condorcet and [Jean-Charles de] Borda. The subject gave me wonderful room for both my analytical and practical interests.

So, by the time I was in my 30s, I was trying to integrate my practical concerns about justice with both mathematical and non-mathematical work on the foundations of the philosophy of justice and of social choice.

Two arguments with a strong public appeal

I won't deny that this is an ambitious book -- relating practical matters of human action and public policy, on one side, and evaluative analysis in general and theories of justice in particular, on the other. I was committed to working on this without deciding, until fairly recently, that I should really write a substantial book on this. But I gradually got convinced that I could not convey what I wanted to say -- at least not convincingly -- without making the project more complete and more securely founded.

As in the past, trying to explain to my students what I am trying to say -- and why -- cleared my own ideas and the ways and means of getting them across. It also made it clear to me how many distinct -- though related -- subjects (including rationality, public reasoning, social choice, democracy, the idea of rights, analysis of class divisions and deprivation of women) have to be simultaneously addressed. The book ended up being much larger than I had first thought.

You urge that the principles of justice should not to be seen in a parochial sense, that it could serve the world better if we have proven ideas of justice.

Even though each culture in the world has produced interesting ideas and thoughts on these subjects, it would be a great mistake, I would argue, to see them as special features of each culture that do not have relevance across borders, and do not relate to one another. Despite the special experiences of people in different parts of the world, our engagements with demands of justice have relevance beyond our parochial boundaries, and can potentially have a global reach.

Just to give an example with a profound narrative from the epic Mahabharata, namely, the debate between Krishna and Arjuna in the battlefield of Kurukshetra that takes the form of the Bhagavad Gita, which is often read as if it is a separate document altogether, but which is actually an integral part of the great epic.

The debate airs strong arguments on two different and competing sides, giving distinct reasons for taking one side or the other in that argumentation. Both sets of arguments have very strong universal appeal, which have relevance well beyond the boundaries of India.

On one side is Krishna's argument for Arjuna to do his duty, as a fighter (as Arjuna is), for the just side; for the victory of a just cause. On the other side is Arjuna's concern that no matter how just the cause is in the process of carrying out this action a great many people would be killed, there would be huge agony of a large part of humanity. He -- Arjuna -- would also be killing people on the other side for whom Arjuna has affection. In the Gita, seen as a religious document, Krishna's arguments prevail, but in the larger document -- in the epic Mahabharata -- the tragedy of the killings, including the agony and the grief, is also brought out with force and sympathy.

Both sets of arguments have powerful universal appeal. I don't think there is any difficulty in understanding what the debate is about -- even if one is not familiar with the Mahabharata, or connected with India in any way.We have reasons to be angry and upset

Kautilya's aim is to argue for a system of social justice which is not reliant on the goodness of human nature but which builds on giving people incentives in the form of carrots and sticks -- a system that is incentive-compatible, to use a contemporary term much used in modern game theory and decision theory.

In contrast, Ashoka wants to make human sympathy and sense of morality and fairness play a big part in the system, without having to rely on the disciplinary force of carrots and sticks. This demands a major change in our behaviour patterns -- and it is for that reasoned change that Ashoka relentlessly argues. That is a huge contrast of approaches, but the arguments on both sides can be understood across the borders of India, or any other country.

Similarly, in other cultures too, in China, in Japan, in the Middle East, in Africa, there have been again and again, ideas that have been very generally concerned with the demands and mechanisms of justice -- its difficulties and its promises -- that can resonate across the world.

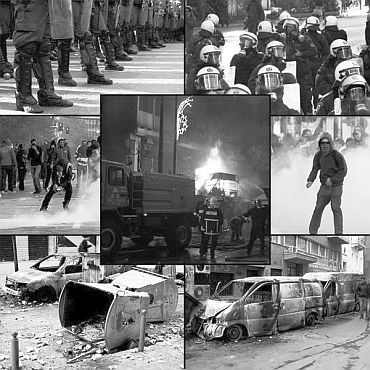

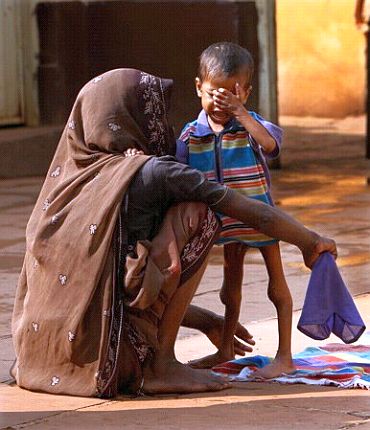

If we move away from theories to actual practice, there are evaluative judgements we can make that have very widespread -- indeed global -- appeal. We have reason to be angered and upset no matter where we are located when we learn that hundreds of millions of children remain undernourished despite the economic prosperity of the world (and the incidence of under-nourishment is very large in my own country, India, despite our rapid economic growth).

We have reason to protest when we learn about tortures that continue in the world, sometimes practiced by the pillars of the global establishment. Or about the fact that there are children and adults dying today across the world because of lack of medical care, or lack of medicine for illnesses that are manageable and sometimes curable for which medicines can be produced easily and cheaply.

The fact that these things are happening can move people across the world with a strong sense of involvement when the facts of the matter are fully known, appreciated and analysed in terms of our thinking. I think we have much greater ability to talk with one other, to understand one other, to appreciate each other's concerns and agonies, than those who take a sequestered view of world civilizations allow.

I tend to think of civilizations in the world as one human civilization, which has had many different manifestations, and which has experienced many different forms of advancement in different parts of the world. The different parts can communicate with -- and learn from -- each other (as indeed has happened historically).

People have always learned from one another, and we can understand each other's arguments, if we try.

We can put our main focus on doing our duty

And there are ideas emerging in the history of the American continents, including those from the American Revolution and the American Civil War.

I think the focus on global reach is an important aspect of my attempts in The Idea of Justice. One aspect of that is what we have just been discussing -- learning from the intellectual history of different parts of the world. A different, but also important, aspect of this global concern is the need to see justice in the contemporary world in a way that does not exclude the idea of global justice for the world as a whole.

We can talk about justice and injustice at the global level, and in particular on how to reduce manifest injustices in the world, and we need not be confined to completely parochial ideas and thoughts. So that's part of the programme of the book: and if people pay attention to that, I would obviously be delighted.

How can we use in a practical sense the philosophies of Kautilya and Ashoka, Krishna and Arjuna in working towards creating a just society?

That is a big question, but I am glad you have asked it. The main issue is this. The arguments of each of them -- Kautilya, Ashoka, and also Krishna and Arjuna -- can be followed and the reasoning behind them examined, scrutinised and when appropriately utilised by anyone located anywhere in the world. We may be persuaded by one side or the other, or try to combine the wisdom on different sides.

For example, a good social system may simultaneously use Kautilya's focus on incentives and Ashoka's emphasis on moral and political maturity. In dealing with global warming, for instance, we may need both carbon taxes and incentives to reduce pollution and more environmental awareness and engagement in reducing our tendency to foul up the world around us. The importance of Kautilya's reasoning, which can be acknowledged, need not lead us to "rubbish" Ashoka's focus on behavioural reform through greater understanding.

Similarly, we can, after scrutiny, put our main focus on doing our duty, in the general line of Krishna's thinking (as Mahatma Gandhi did), or on producing a more just world in line with Arjuna's consequential thinking (in a way that Rabindranath Tagore clearly uses). And we can combine the two through a reasoned synthesis. Public reasoning can make room for different kinds of arguments to be taken into account, as I have tried to discuss in my book.

Democracy goes beyond just elections

I think there are at least three interesting things about democracy and famine. The first is the fact that famines often are not just results of natural disasters, but something that is sometimes caused by human stupidity of public policy. When a famine occurs, it occurs because it has not been prevented through counteracting human action.

So, humanity is very strongly involved in what may otherwise look like a natural disaster. That makes the subject matter of famine, at least, suitable for an analysis of justice and amenable to be influenced by a working democracy.

The second is the way a functioning democracy can focus attention on a possible famine. Obviously elections help to prevent famines, since the government in office has strong reasons to avoid the occurrence of a famine (free elections are hard to win just after a famine). But democracy goes beyond just elections.

There is the important role of public discussion and of a free media. Open public discussions can bring out the threat of famines; can help to pin responsibility on governmental failure to take appropriate actions; can point to ways and means of policies that work (and have worked elsewhere in the prevention of famines).

It is very important to recognise how and why public reasoning has a big part to play in preventing calamities that can be prevented. Third, even though elections are difficult to win after a famine, this is not just because of a majority of the people are affected by famines.

In fact, it is worth noting that the proportion of the population affected by famine is always quite tiny, hardly ever more than 10 per cent and most often less than 5 per cent of the population. If it were the case that only the potential famine victims vote against the government for not doing enough to prevent a famine, that would not be a majority.What makes majority vote effective in famine prevention is our ability to sympathise with one another, to see the predicament of each other in a social life. So, while the existence of famine exposes the misfortune and miseries and the agonies from which a small minority suffers, that agony gets reflected in a public anger that is much more widespread and not confined only to the minority group of famine victims.

Public reasoning makes us understand each other's agonies and help us to take up issues in which we may not personally be directly involved. Public reasoning is, thus, very important in the working of democracy and for famine prevention.

It is also very central to understanding the demands of justice and imperatives of reducing manifest injustice. That is the way Gandhiji waged the battle against untouchability. Even though the proportion of the population of untouchables is small, the movement did not include only the untouchables, it included increasingly the whole of the Indian population.

Famine gets a lot attention, but not hunger

This is a matter of deep interest both for a theory of democracy and for a theory of justice. And, in my book I try to relate the two. While famines get immediate public attention in a working democracy, other deprivations -- including chronic hunger and under-nourishment -- demand more democratic engagement.

Famine gets a lot attention, but not hunger.

Famines are very easy to politicise. It is hard to miss the fact, when that is the case, that there are people dying in the streets, and it looks like an intolerable situation. More reasoned and committed engagement is needed to appreciate the deprivation involved in quiet hunger which does not kill anyone then and there, but increases the probability of dying from illnesses in a statistical way, and which prevents the full development of a child's physical and mental faculties.

Democratic practice needs more sophistication and more engagement to politicise these deprivations. I think it is a failure of the practice of democracy as it has been practiced in India that despite the opportunity to politicise the incidence of widespread hunger, the media and public discussion has failed to do so. But there is nothing inescapable in that because what has not been done yet, can be rectified.

The same can be said about gender disparity. When I first started working on women's deprivation and gender inequality in India (in the 1960s), I had a very unsympathetic press -- there was a kind of lack of interest in it. Political sympathies were also quite limited then.

Those on the "left" of Indian politics thought that I was diluting the inequality related to class and in some ways undermining the big importance of class division. Those on the "right" often thought that I was focusing on a "non-problem." I was told that this was a non-issue because Indian women see their own well being in terms of the well being of the family. That is certainly the way women often think of these issues, but that comes from coming to accept gender inequality as a natural state of affairs.

In fact, the traditional value system may even prevent women from having their individuality, having adequate respect for their own well being in addition to the welfare of the family. That is a result of acceptance of inequality -- not a sign that there is no inequality worth our attention.

Things have changed in India now and there is much greater awareness of inequality between women and men now. This is largely due to public reasoning and the activism of women's movements and more generally a greater political awareness. The same can be done about the continued curse of under-nourishment in India. We need more engagement and more reasoning on why and how hunger not only causes immediate suffering but also dooms people's long-run lives.