Photographs: Reuters M K Bhadrakumar

Henry Kissinger's perspectives on India have changed over the years. So how does India take to the mellowed Dr Kissinger?

India's elites may have dropped their earlier allergy toward Kissinger, who turned 90 last week, but they are on guard still, feels Ambassador M K Bhadrakumar.

Anyone who worked as a diplomat in the latter half of the 20th century would have his private story to tell regarding Henry Kissinger.

So let me begin with mine, circa February 1972 in a cavernous room of the Union Public Services Commission in Delhi, while seated awkwardly across a big table facing a phalanx of hostile-looking elderly gentlemen who were to judge my credentials to become a diplomat.

I had expected a fair portion of the interview to be on a famous American, Tennessee Williams, on whom I did my PhD work. But Kissinger who had just returned from the secret visit to China hijacked the interview.

To my great relief the interview went very well since a congenial atmosphere easily formed with a consensus opinion that Kissinger was not at all a good thing for India.

For me it was easy to be emotional, because as a leftist student activist I saw Kissinger anyway as the ogre of Vietnam. The intellectual understanding that led to profound admiration followed in later years.

The Indian elites never really got to like Kissinger. The Kissinger saga predates his China visit. During the South Asia crisis of 1971 Kissinger regarded India as a 'Soviet stooge' and he refused to accept the Indian accounts of genocide in the then East Pakistan.

We never forgave him. And to add insult to injury, he sent the USS Enterprise to the Bay of Bengal to intimidate India. We felt outraged and there is nothing worse than passive outrage.

But then, there was nothing personal in all that on Kissinger's part. He also brushed aside the cables from the American diplomats based in Dacca (now Dhaka) on the 'reign of terror' let loose by the Pakistani army, because human rights issues never bothered him.

This was a consistent streak in Kissinger's outlook -- his very lack of idealism and his conviction that there could be only one immutable principle in foreign policy, namely a country's self-interest.

It is not that he entirely lacked liberal instincts. But 'liberalism' was only one principle among many and it could only be a general principle at that, and taking into account the stubborn realities of the world, often it required some bending.

Please ...

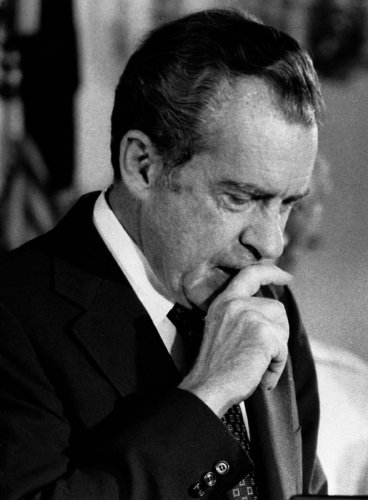

Nixon and Kissinger did not want to displease Pakistan's Yahya Khan

Image: Then US president Richard M NixonPhotographs: Reuters

Plainly put, the Richard Nixon administration did not want to displease Pakistani dictator Yahya Khan who was providing a secret communication link for the US's quest for rapprochement with China.

Besides, the US wanted to show to Beijing that it would support its allies in Pakistan come what may.

The Cold War dimension was unquestionably there, too. For one thing, there was the possibility that the crisis could mutate into a China-Soviet conflict and/or a US-Soviet confrontation.

A controversial CIA report added fuel to the fire, by leading Kissinger and Nixon to believe that India's intention was not only to dismember Pakistan, but also to destroy the Pakistani armed forces.

The CIA input prompted the US to transfer planes to Pakistan and to tell the Chinese that 'if you are ever going to move this is the time.'

On the same fateful day -- December 8, 1971 -- Nixon and Kissinger decided to send the USS Enterprise and other naval forces into the Bay of Bengal so that a 'Soviet stooge, supported by Soviet arms' would be stopped in its tracks from over-running Pakistan.

Two days later, Nixon sent a 'hotline' message to Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev to 'restrain' India, while also nudging China to move against India and guaranteeing that the US would support Beijing if the Soviets retaliated.

Strangely, Kissinger really believed that China was 'going to move. No question, they're going to move.' But Nixon wasn't so sure that Beijing and Moscow were about to go to war.

Kissinger can be inscrutable. Did he exaggerate with a definite purpose?

At any rate, by then the Soviets had assured the White House that the Indians had no intentions to attack West Pakistan and that they were working with Indira Gandhi to arrange a ceasefire, which of course took effect on December 16 following the surrender of the Pakistani forces in East Pakistan.

Please

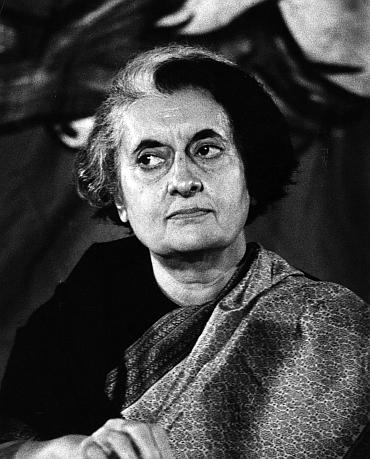

Kissinger was appalled that such a phoney person could get away with threatening the status quo

Image: Then prime minister Indira GandhiPhotographs: Reuters

All this is documented history. Kissinger played the key role in micromanaging the US moves. To my mind, clearly, he wasn't punishing India.

His calculus had two angles: a. The US' Cold War rivalry with the Soviet Union and his apprehension of a collapse of the 'balance of power', and B. The anxiety to keep the US' nascent Chinese arm.

We Indians mistook this as his 'tilt' to Pakistan, but neither Pakistan nor India figured except collaterally in Kissinger's scheme of things -- as minor instruments that could spoil the big symphony.

But the Indians somehow convinced themselves that Kissinger had an entrenched, visceral hatred toward their country. His irritation with India at that point in time was that

Indira Gandhi was upsetting the preservation of the worldwide balance of power. This had everything to do with Kissinger's conception of foreign policy. Kissinger remained steady in his refusal to confuse foreign policy with theology.

He saw no scope for moral condemnation in foreign policy. The Indians, on the other hand, insisted on playing on both sides.

Self-interest guided Indian foreign policy most of time and moral condemnation never perturbed India or hindered it from doing things that were in its self-interest, but India also reserved the right to resort to moral condemnation of the US's behaviour.

Kissinger thought this was rank hypocrisy. His vituperative remarks about India and Indira Gandhi can be seen almost entirely in this light.

He judged that while on the one hand India proclaimed non-alignment as the moral equivalent of the two sides that straddled the Cold War crises, on most issues it ended up tilting toward the Soviet position or where it was not patently possible, ended up remaining aloof rather be supportive of the US.

Kissinger felt irritated by India's day-to-day tactics. He was unmoved by the ideals of the shared affinities the two countries lavishly proclaimed, being democracies and so on.

What mattered to him were the political choices that India was prepared to make.

Kissinger remained genuinely unconvinced that Indira Gandhi's anguish over the repression in East Pakistan was anything but a pretext and it led him to think of her and the country's policies at that point as driven by aggressive intentions.

Kissinger was appalled that such a phoney person could get away with threatening the status quo in the world order.

In those uncertain times in the early 1970s, the preservation of the status quo subsumed all other considerations on Kissinger's mind.

Please ...

He grants that Indian policies are born out of its unique cultural and historical experience

Image: Henry KissingerPhotographs: Reuters

His entire foreign policy sensibility was geared to the balance of power ethos and there was hardly any room for private morality. Robert Kaplan recently wrote about how it worked: 'Realism is about the ultimate moral ambition in foreign policy: The avoidance of war through a favourable balance of power.'

Of course, in later years Kissinger expressed public regret over his anti-India comments. He admitted slyly, 'The fact we (the US and India) were at cross purposes at that time was inherent in the situation but she (Indira Gandhi) was a great leader who did great things for her country.'

He politely explained that the caustic things he said about Indira Gandhi and the Indians did not form part of a 'formal conversation' and was 'Nixon language.'

But the sense of humiliation remains in the Indian mind and the remarks still rankle -- 'The Indians are bastards anyway. They are starting a war there (in East Pakistan).'

And, honestly, how far Kissinger meant his regret is also difficult to tell. What matters, perhaps, is what he thinks of present-day 'emerging' India.

Evidently, his enthusiasm for India some six or seven years ago following the visit by President George W Bush to India and the promise of an unprecedented level of US-Indian cooperation and interdependence has dissipated.

However, he is much more tolerant in his understanding of Indian policies. He is willing to grant that Indian policies are born out of the country's unique cultural and historical experience.

In a 2006 essay (external link) he acknowledged that American exceptionalism and the Indians' outlook on their international role are fundamentally different: 'Hindu society does indeed also consider itself unique but, in a manner, dramatically at variance from America's. Democracy is not conceived as an expression of Indian culture but as a practical adaptation, the most effective means to reconcile the polyglot components of the State emerging from the colonial past.'

'The defining aspect of Indian culture has been the awesome feat of maintaining Indian identity through centuries of foreign rule without, until very recently, the benefit of a unified, specifically Indian, State. Huns, Mongols, Greeks, Persians, Afghans, Portuguese and, in the end, Britons, conquered Indian territories, established empires, and then vanished, leaving behind multitudes clinging to the impermeable Hindu culture.'

He understands non-alignment better -- namely, that given India's disinterest in spreading its culture or its institutions in the world without, India would not make a 'comfortable partner' for the US.

The point is, India's traditional notions of equilibrium and national interest, especially its national security requirements guide its global activities very precisely.

Please ...

Kissinger rejects the notion of India being a counterweight to China in US policy

Image: Indian Prime Minister Manmohyan Singh with Chinese Premier Li Keqiang in New DelhiKissinger has written that Indian involvement in international affairs will manifest at different levels. In its South Asian neighbourhood, the attempt is to maintain Indian hegemony.

Kissinger sees India's China problem as of a great power confronted by a comparable rival, but he estimates that so far the preoccupation has been to create a security belt against military pressure while neither power has got engaged in a diplomatic or security contest over pre-eminence in the heartland of Asia.

And he sees no change in the foreseeable future also because both India and China realise that they have too much to lose from a general confrontation.

Kissinger rejects the notion of India being a counterweight to China in US policy. He sees there is no scope for a US-India condominium against China because both countries are interested in maintaining a constructive relationship with China and while the US' global strategy to build a new world order could gain from India's cooperation, India will not only refuse to serve as America's foil with China, but will resent any attempts to use it that way.

At the same time, he sees that India's 'Look East' policy works in harmony with the US' regional policies in Southeast Asia insofar as both countries are interested in an inclusive regional architecture that also includes China, Japan, ASEAN and themselves too.

On the whole, Kissinger sees that globalisation has reinforced the incentives for both the US and India for cooperation. Both the major political groupings in India are advocates of India's integration with the world economy. And a 'geopolitical confluence of interests' has also emerged with the end of the Cold War.

Interestingly Kissinger has been a staunch supporter of the 2008 US-India nuclear deal. He opposed the US sanctions against India following the nuclear tests in 1998 and espoused that India should be treated as a nuclear country whose capabilities in the nuclear field are irreversible.

Evidently, Kissinger's perspectives on India have changed over the years. Much of this is to be understood in terms of the post-Cold War setting, while his panache for realism and the primacy he attaches to the 'balance of power' have not withered away.

Arguably, his continuing role as the flag carrier of US-China cooperation and interdependency can be explained this way.

How does India take to the mellowed Kissinger? India's elites have also dropped their earlier allergy toward Kissinger, although they are on guard still.

His advocacy of China's harmonious rise doesn't go down well with the Indian pundit. Besides, there is a credibility problem, since it is virtually impossible to fathom what is really going on in Kissinger's seamless mind.

His past and present views on India have been so dramatically divergent. But the new Kissinger probably senses a change in the Indian attitude.

Or else, he wouldn't have travelled to Kolkata in November 2007 to call on the then chief minister of West Bengal Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, a top leader of the Communist Party of India-Marxist, in an effort to convince him that the US-India nuclear deal was a good thing to happen.

However, while in Kolkata, Kissinger again got things all wrong about India and the Indians. He said Bhattacharya reminded him of Deng Xiaoping and he openly praised the 'Communist government committed to investments and development.' Bhattacharya was voted out of power in 2011.

article